PUBLIC HOUSING: Difference between revisions

(added new photo) |

(changing neighborhood to Excelsior only) |

||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

[[Public Housing Comes Full Circle | Prev. Document]] [[The Goodman Building | Next Document]] | [[Public Housing Comes Full Circle | Prev. Document]] [[The Goodman Building | Next Document]] | ||

[[category:housing]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:redevelopment]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:Potrero Hill]] [[category:Chinatown]] [[category:Richmond]] [[category:racism]] [[category:Excelsior | [[category:housing]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:redevelopment]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:Potrero Hill]] [[category:Chinatown]] [[category:Richmond]] [[category:racism]] [[category:Excelsior]] [[category:Visitacion Valley]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] | ||

Revision as of 12:58, 12 July 2014

Historical Essay

by Josh Alperin

Bernal Dwelling at Folsom/Cesar Chavez/Harrison, here in 1996, rebuilt in the 2000s.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Valencia Gardens public housing in 1996 between 14th and 15th Streets, Valencia and Guerrero, before its reconstruction.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The 1937 U.S. Housing Act provided the necessary institutional and financial background whereby cities would fulfill the role of steward and guardian to projects financed by a federal government comparatively beneficial in welfare funds. 1938 was the year that San Francisco, along with all other major cities, established its own municipal housing authority. The decentralization of administration, leaving stewardship in the hands of local agencies has meant that public officials must contend with the pressures of meaningful constituencies to determine whether to build and where to locate the housing. As a result, none of San Francisco's projects are found in moderate or affluent neighborhoods.

Within its first year nationally renowned architects had completed plans for five unique housing designs, each slated for very different parts of the city. Work began quickly on three of the projects, the most prominent of which was Holly Courts, located on the southern side of Bernal Heights between Holly park and Mission. Designed by Arthur Brown Jr. , also the designer of Coit tower, the project called for 118 units fronted on the street, surrounding an interior of landscaped courts and play spaces. Simultaneously work was started on Potrero Terrace on the south side of Potrero Hill and at Valencia Gardens in the Mission. The characteristically liberal design models of early public housing represent attempts at social engineering that have since lost their validity.

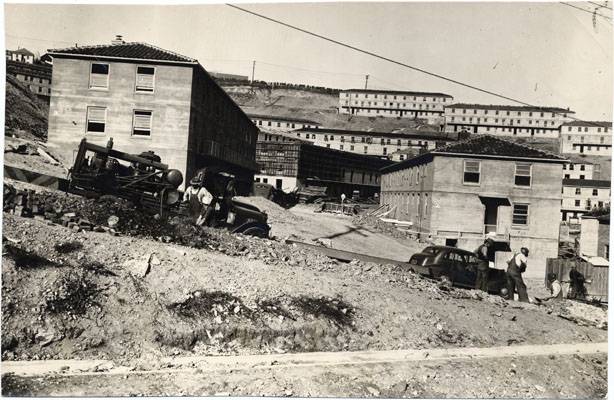

Construction of Potrero Terraces, 1941.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

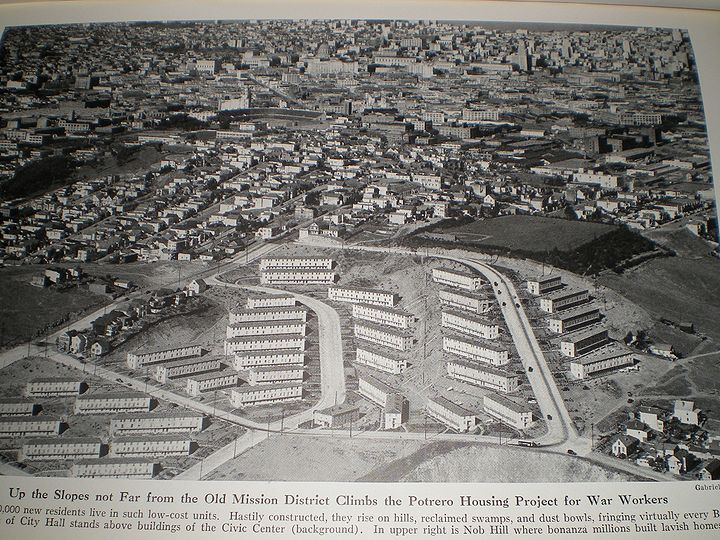

Potrero Terraces, 1943, looking north/northwest. You can see Seals Stadium in the background middle.

Photo: "We Grew Up in San Francisco" Facebook group

Although widely used in European cities throughout the 20th century, publicly funded housing did not seriously penetrate the U.S. landscape until the Great Depression. An effort to create better and cheaper housing, the first subsidized housing program of 1937 wasn't enacted until it could be coupled economically with the more pressing objective of reducing unemployment and thus stabilizing the economy. Beyond simple trends in the housing industry, the factor that has contributed most to the design and site locations of public housing projects has been the aggressive resistance of private interests. Even though public ownership is an anomaly in the U.S. economic system, it inevitably affects the housing market. Private industry has ostracized the projects both physically and financially in order to minimize their effect. Early concessions to the private housing industry include provisions requiring "equivalent elimination" of "substandard" units for each new unit of public housing. This way no fluctuations in surplus would be caused. It was also urged that public housing be clearly differentiated from the rest of the housing stock, leading in later years to typically austere and monolithic structures.

The deterministic nature of early public housing shaped a panopticon-like, segregated microenvironment, later expressed clearly by HUD as "a city within the city". The Holly Court design of 1938 is structurally a stylized borrowing of the self-enclosed ward grafted on to the loosely urbanized landscape of Bernal Heights in pre-World War 2 San Francisco.

The concept of creating 'a city within the city' was at the time the dominant fashion throughout the housing industry. Pre-World War 2 San Francisco was vastly pockmarked with huge tracts of open space, leaving size considerations nearly absent from the calculus of development. In 1941, the Lake Merced Private Development Company formulated plans for developing nearly 50 acres of land around Lake Merced, bordering the Ingleside golf course. From the beginning, comparisons were being made to a simultaneous plan submitted by the local Housing Authority to the federal government for funding. This "Woodland" project in Sutro Forest on the southeast side of Twin Peaks would cover 30 acres in a sparsely settled area. The public/private competition was made clear in the local media. Enthusiasm and support for public housing was higher at that point than at any other time in history. The nearly completed Sunnydale project, then the largest west of Chicago, covering the floor of Visitacion Valley, was a testament to civic pride.

The "Woodland" and Lake Merced projects were structurally akin in their efforts to simulate a semi-rural world of seclusion, security, and leisure. In both areas the amount of acreage set aside for buildings was less than one third of the total land space. The majority of land would be kept open for recreational use like parks and tennis courts, or simply crafted to provide residents with a rustic ambiance. Ultimately, the "Woodland" project was to succumb to the pressures of local politics. The necessity for rezoning the area to the higher density 'Residential B' status was met with protest by the local homeowners, while simultaneously the privately funded housing at Lake Merced continued unimpeded.

World War 2 interrupted all non-war related government programs, leading public housing to fall prey to defense needs. Since San Francisco's five original projects had already been set in motion, all were completed by 1943 when Westside Courts at Post and Broderick was open to residents. The course of public housing was drastically diverted in order to establish thousands of simplistic, barrack-like, temporary houses for the newly arrived industrial working class. These new workers rushed to the Bay Area to find work in the booming war industries. The three hubs of this activity included the shipyards at Hunters Point in the southeast corner of San Francisco, the docks across the bay in Richmond, and those in Marin City. In San Francisco, 30,000 war workers were housed in temporary, dormitory housing stretching along the edge of the bay from Potrero Hill down to Hunters Point. African Americans accounted for 40% of those housed at this time. Besides the minimal "Negro Experiment" at Westside Courts, this war housing was the first racially integrated housing in San Francisco and the first time that public housing funds were to significantly affect non-whites.

The energetic origins of public housing can only be understood if we take into account the initial target populations. The "deserving poor" mentioned in the 1937 Housing Act were whites that were considered to be temporarily offset by the long years of depression. Early pamphlets of the local Housing Authority advertising "model home days" at the Sunnydale and Valencia Gardens sites depict groups of white children playing in the interior common space, to the side is a glimpse of a fully mechanized kitchen from 1940s middle class America. The diversion in public housing caused by the war permanently altered the situation. Ideologically housing of this type has always attempted to foster certain middle class values amongst its otherwise poor population. But from the war years on, blacks and other non whites have comprised the large majority of residents. This transfer from the temporarily "submerged" middle class to poorer, more marginalized groups has had serious repercussions demographically and politically.

The more classically American, privatized solution to the housing problem was in full swing shortly after the close of the war. Originally initiated in 1934 by the Federal Housing Administration, subsidies facilitated movement to the suburbs by underwriting both the construction and lending industries. Concurrently, the Highway program of the post-war era helped to open up vast quantities of cheap land for easily financed development. At a moment when public housing was commonly being criticized and project funding withheld, private industry was accelerating its activities. No counterbalancing subsidy was enacted to improve inner city housing. Ubiquitous racism severely stifled the credit options and mobility of various ethnic groups.

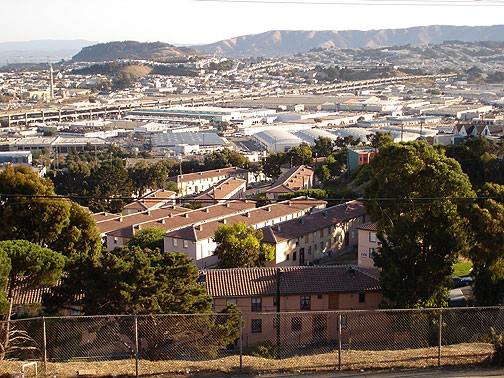

Potrero Terrace housing project from hillside above, looking south, 2008.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Temporary war housing left a lasting mark on the face of San Francisco. The dormitory locations would later determine many of the future sites of permanent projects while simultaneously delineating much of the settlement patterns of Blacks within the city. Today, with the exception of the Western Addition and the Ingleside district, much of the black population of the city is focused around the neighborhoods of these former sites. Increasingly the temporary housing had become a more segregated black phenomenon as the more socially mobile white middle class fled the city to stake claims in the hinterlands of suburbia. Even though this housing was slated to last for only 5 years, much of it remained assembled and served as shelter until 1964. No dismantling of the dilapidated structures even began until the early 1950s, five years after the close of its original, projected life expectancy. At this time it was private interests that urged the city to acquire the lands from the federal government. It was thought that the city's economic viability rested to a certain degree on selling off these large tracts for manufacture and industrial use.

In the early 1950s, from his helm as the regional director of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, Justin Herman, a chief architect of modern San Francisco, saw the real necessity of acquiring the war housing from the federal government. Acquisition of the land would allow the city to squeeze as much life as possible out of the already decrepit buildings. With the city already pursuing its A-1 redevelopment project in the Western Addition, a Black and Japanese neighborhood, the former war worker housing might provide relocation housing for the soon to be displaced. Holding on to war housing meant averting both the housing chaos caused by large displacements and the predictable racial tensions.

In 1949, after a national lull in public housing, the federal government enacted a new Housing Act including large provisions for more housing and the critical Title 1 for urban redevelopment. This opened the way for cities to begin reconstruction of the newly labeled "blighted areas." Another subsidy to private industry, the legislation allowed local agencies to borrow federal money to acquire and clear city lands. The lands were then resold for private development, the revenues from the sale were returned to the federal government with any difference being covered by federal grants.

Back in 1946 the city's Mayfair Heights project was a prototype for the "wonders" of private enterprise. One hundred acres of land including the cemeteries atop Calvary and Laurel Hills, centered around Geary and Masonic streets, would be redeveloped to make way for vast housing tracts and large retail outlets. By the end of 1947, city planners and corporate leaders had already publicly announced their A-1 plan for the Western Addition. The media campaign to convince the city of the need to redevelop the "blighted areas" had begun in earnest. Redevelopment was a critical element of a budding corporate vision for San Francisco both as an administration and finance center locally as well as for the recently conquered region of the Pacific Rim.

San Francisco Redevelopment Agency leader Justin Herman, had understood the role of public housing all along. With the city pursuing massive projects of blight removal, public housing would pick up the pieces of population relocation, essentially providing another subsidy to private investment. The new international vision for the city was critical to redevelopment. As the city began to lose retail and tax revenue to the suburbs, certain city-oriented business leaders united with "progressive" politicians in formulating the new city plan. As a "headquarters" city and hub of the convention industry, the need for a minimally skilled working class was diminishing. Especially within the crucial city center, overt misery needed to be eradicated both to boost the city's image and to make way for white collar workers in the burgeoning finance and administration industries.

Although most of the large allocations set up in the 1949 Housing Act never produced the amount of housing that was projected, San Francisco saw a heavy flow of new public housing up until the mid 1950s. Most of the new projects were structurally larger and more simplistic than the original batch. Fenced areas and parking lots replaced the enclosed court designs of earlier days. The funkiest of the new projects was the high density Ping Yuen at Pacific and Powell, finished in 1952. It superimposed pagoda-like external balcony corridors over an otherwise functional building.

Ping Yuen Public Housing, 1999.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Other projects from this era include the sprawling Alemany street units placed next to Highway 280 and the Bernal Dwelling along Cesar Chavez street at Harrison. The Yerba Buena Plaza at Laguna and Turk went up in 1955. The massive Hunter's View and Harbor Public Housing projects went up in place of some of the former war housing in the Hunters Point area, while a new structure was placed in North Beach, overlooking the bay at the corner of Bay and Columbus.

In 1952 the local Housing Authority denied the admission of blacks into the new North Beach project. The "neighborhood pattern" clause of a 1942 Housing Authority resolution barred the "co-mingling of races." The stated goal of Housing authority was to preserve the racial composition of the neighborhoods in which projects were placed. This meant that blacks could only move into projects in sufficiently black neighborhoods. Westside Courts was the only project at this time that had what was called a "Negro Experiment", allowing the inclusion of blacks. The temporary war housing was the only publicly funded housing support for a black population now facing very high rates of unemployment due to great losses in local industrial labor. The NAACP defended the case of Banks v. the San Francisco Housing Authority, which lead in 1954 to official desegregation of all San Francisco housing projects. The public housing of this time, although much less inspired than that of the initial era, succeeded in creating "a city within the city" by dint of its size and aesthetic exclusion.

The means tests that limits entry into public housing to only the poorest of society served to create the stigma that such programs suffer from today. The demographic shifts created heavy pockets of extreme poverty in already neglected neighborhoods. Housing projects, difficult to police and covering one or more city blocks, incorporating both open spaces and strategic heights, became magnets for illicit behavior. The liberal planners that once initiated housing of the poor were already in the 1950s joining the ranks of the dissenters. This controversy--mixed with the increasing fiscal conservatism of the Eisenhower administration--reduced public housing production.

Throughout the sixties, much of the new public housing built in the city went to accommodate those displaced by redevelopment. In particular, the Western Addition received several low-income housing projects. Both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations were committed to maintaining support for public dwellings. Urban riots in the latter part of the 1960s demanded solutions for festering problems in all inner cities.

A pragmatic shift was executed at this time. In response to political criticism from all sides and the severe distrust directed at local Housing Authorities, the government turned to the private sector as a way to rescue the programs. Questions of management and ownership would have to be resolved if any subsidies were to remain. In 1965 the section 23 program (predecessor of the 1974 section 8 program) and the "turnkey" program were introduced. Section 23 enabled low-income families to rent units in privately owned housing. The Housing Authority paid the difference between the unit's market value and a proportion of the tenants' income. The turnkey approach allowed a developer to enter into a contract with a local Housing Authority by which the developer built and then sold the housing to the local Authority at a stipulated price.

Throughout the following years, most new public housing has followed these two routes. The turnkey approach has been labeled by developers as the "proper role of government" in support of private industry. These interests support public housing.

San Francisco has over 30 neighborhood development corporations that either manage or build public housing. One result has been to remove pressure from a local Housing Authority deeply embroiled in controversies of corruption and mismanagement throughout the '70s and '80s. The neighborhoods most effected by turnkey development and section 8 housing have been the same poorer neighborhoods: Western Addition, Hunters Point, the Mission and the Tenderloin.

Turning the reins of development over to private industry resulted in the production of housing projects, which from the outside, are indistinguishable in form from other houses. Increasingly throughout the 1980s small development companies have built projects throughout the city which simply mimic the design character of their neighborhood. The big change for public housing didn't come until 1991. San Francisco's much-praised prototype for project demolition and redesign is Robert B. Pitts, the neo-victorian townhouse complex at Turk and Scott streets in the Western Addition. The development downscaled the 332 apartments of Yerba Buena Plaza West into a 203 unit complex. The new homes are two-story, vinyl sided, "faux private" townhouses with separate street entrances.

This project is considered a landmark for its technical breakthroughs in design. Critically, a "hierarchy of territorial control" is maintained by giving each household its very private space, clearly defined from the common inner court as well as from the street. No "undefensible spaces" are present, and clear visual separation of residents is obvious. By limiting escape routes, strategic overlooks, and access to off-the-street space, this housing joins the latest in security design with a reinforcement of middle class values. Whether it is real home ownership or "faux" home settlement, the design motive is ideological and evident. The rehab of the infamous Pink Palace into the Rosa Parks senior apartment complex is another example of this strategy. The once deteriorated, open-balconied "police puzzle" is now a fully enclosed model senior mini-city. The three pillars of defensive enclosure, visual separation and restricted access were also utilized in the recent redesign of 157 dwellings at the Sunnydale projects.

The new HUD HOPE 6 program funds demolition and new construction for the Bernal Dwelling and Yerba Buena Plaza East. The original plan for Yerba Buena, created by the same company that reconverted Sunnydale, calls for the megablock to be subdivided into component blocks of row house walk-ups. Separately accessible, enclosed backyards will replace former open spaces entirely. The plan still faces resident resistance and one-to-one replacement housing is only guaranteed on paper.

The catastrophe of destroying lateral survival networks is unquantifiable. As the past has shown, many residents will be pushed out of the city, most likely to Oakland or Richmond, or simply forced on to the street.

Architectural designs that utilize the concepts of "defensible spaces" are really nothing new. The concentric rings of definable, secure areas have been fundamental to public housing forms all along. The new element of the recent reconstructions is the relative ease that they provide to the police. Controlling the neighborhood becomes much simpler. Defensible spaces have always been those areas where neighbors could view the good and bad behavior of others. This social pressure was supposed to promote a collective morality. The new intensification of these spaces' manageability is both a reflection of the design's failures and the increased atomization of society. Architecture itself will never eradicate poverty or any aspect of it simply because it is not meant to.

Housing is a basic human need--its exorbitant price increases the general costs to live and that makes everyone more vulnerable. Public housing slightly mitigates this relationship, but does not change it. In a capitalist economy, the survival of public utilities and services depends in the first place on the advantages and subsidies that they provide private industry.

Potrero Terraces overlooking I-280 from east slopes of Potrero Hill, 1996.

Photo: by Chris Carlsson