Saving Telegraph Hill 1890-1918

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Gray Brothers Quarry, southwest view up Telegraph Hill from Lombard and Montgomery, January 15, 1915.

Photo: San Francisco National Maritime Museum, A12.17.144n

George and Harry Gray dug at the east face of Telegraph Hill for about 20 years, mostly with the blessing of City Hall. They persevered through bankruptcies, barrages of rocks from irate Irish and Italian hill dwellers who sometimes saw their small homes tumbling down the cliffside after a quarry explosion. The Gray Brothers ignored and bribed their way through court orders and wide social opposition, even shootings of quarry personnel. In 1909 the Gray Brothers disguised the detonation of several dynamite blasts by timing it to coincide with the fireworks of the 4th of July celebration, but irate neighbors knew what had happened and chased the quarry workers from the site.

The Gray Brothers weren't particularly smart and didn't even put much value on their own lives. Their cashier was shot and killed in 1910 when an unpaid worker lost his temper. And George Gray himself was murdered by a Joseph Lococo in 1915 when Mr. Lococo grew tired of demanding his back pay (a mere $17.50).

The Gray Brothers Quarry on Telegraph Hill

Photo: Greg Gaar Collection, San Francisco, CA

The movement to save Telegraph Hill appeared among a group of women, mostly from other parts of San Francisco, not Telegraph Hill itself. Alice Griffith, Elizabeth Ashe and eight other women formed the Willing Circle in 1890 which eventually became the Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Association. Their efforts focused on resisting the quarrying of the hill, but also they tried to improve the neighborhood by providing classes in homemaking, a Boys' Club, and a settlement house at the crest of Vallejo which provided two nurses for locals' needs. Once the Italian neighbors overcame their initial suspicion they began giving fruit and vegetables to the house, and an evening club for girls working in the canneries was begun. Alice Griffith was the persistent force, badgering city officials, local societies and merchant associations, to halt the destruction of Telegraph Hill. She found lawyers to take on the Gray Brothers, and enlisted the aid of the famous John McLaren to plant flowering shrubs atop the then-barren Pioneer Park at the summit. After years their efforts finally caught the public's attention. The local press began to feature the story, and sailors would obligingly hike up the hill only to fall over the side and gain them even more publicity! The Improvement Club was joined by the daily press, but a number of local unions and their papers also took up the cause, including the Coast Seamen's Journal of the Sailors' Union of the Pacific.

All blasting permits were revoked and the crushing machines stopped by court order in October 1903, but it would be more than a decade until the demolition of Telegraph Hill really stopped.

--Chris Carlsson

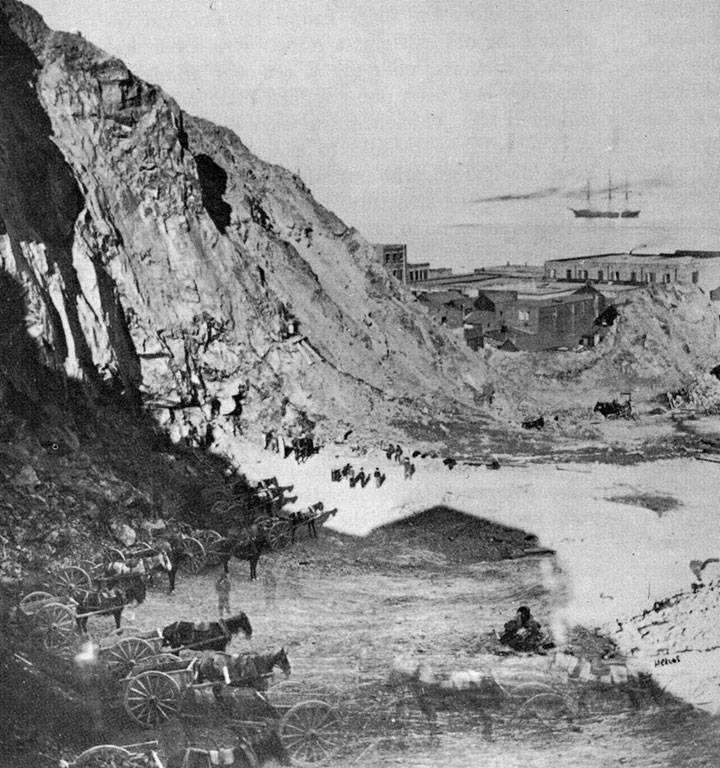

Telegraph Hill quarry, 1870s.

Photo: David Myrick

READ MORE:

North Beach: The Italian Heart of San Francisco by Richard Dillon with photographs by J.B. Monaco, Presidio Press: 1985.

San Francisco's Telegraph Hill by David F. Myrick, Howell-North Books: 1972