1901 General Strike on San Francisco's Waterfront

Historical Essay

by Laurence H. Shoup

originally published as Chapter 11 in Rulers and Rebels: A People’s History of Early California 1769-1901 (Author's Choice Press: New York 2010)

Short summaries of the 1901 Strike and the Employers' Association are available.

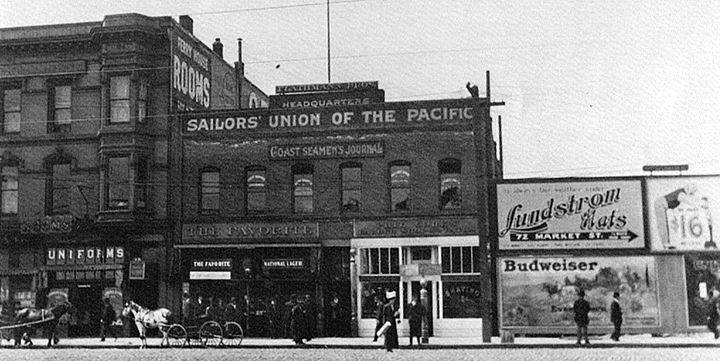

Sailors Union of the Pacific building, c. 1900.

Photo: Sailors Union of the Pacific

Only seven years after the defeat of the American Railway Union's 1894 strike, a massive, three month long strike on the San Francisco waterfront resulted in a triumph for the rank and file and a strengthening of the labor movement. The strike began on July 30, 1901, when the City Front Federation, representing over 15,000 men from fourteen San Francisco waterfront unions, led by the Teamsters, the Sailors Union of the Pacific, and four different Longshoremen’s Unions, walked off the job. This strike was the largest and most significant in the history of California to this point in time.

Although the great waterfront strike of 1901 developed out of a complex set of circumstances unique to its time and place, at the heart of the struggle was the continuing story that new unions were claiming freedoms and asserting their human rights, while at the same time, most of the leaders of the ruling class of San Francisco were refusing to accept any role for the working class in economic decision-making.

Teamsters’ Upsurge September 1900

The strike’s immediate origins can be traced to the formation of the Teamsters’ Union in August of 1900. This event was to be of special importance for both the 1901 waterfront strike and the future of the San Francisco labor movement. Led by Michael Casey, the union was initially small, less than 50 members, but the men who drove the horse teams often worked more than twelve hours a day, some even 18 hours a day, seven days a week at low wages ($3.50 to $16 a week) and under very competitive conditions; virtually all of them were ready to assert their humanity and respond to the union call (Cronin 1943:40).

Mike Casey, head of Teamsters Local 85, pouring beer at a friendly gathering in the park, c. 1905.

Photo: courtesy Maggie's World

On Labor Day 1900, McNab & Smith, one of the leading draying firms, in an employers tactic typical for the time, tried to break the new union by firing drivers who refused to quit the union. Casey and the union men called upon the remaining drivers to strike the offending firm, and when, to the shock of McNab and Smith, almost 100 men went out, the employer settled after only one day, immediately reinstating the discharged unionists. In the wake of this quick victory San Francisco saw one of its fastest single union expansions ever. In the space of only a few weeks, about 1200 men joined the Teamsters’ Union, and in mid-September Casey and his membership demanded improved hours and working conditions.

The employers group, the Draymen’s Association, wanted a stabilization of the all-out cutthroat competition characteristic of the industry, so it was open to an agreement that would prevent new competitors from entering the field except as members of the Association. The Association was therefore willing to recognize the union, and on October 1, 1900 a detailed formal agreement was signed. The workers got a regular 12 hour day, with overtime pay for over 12 hours and for work on Sundays, as well as the union shop and an agreement that no assistance would be given to public drayage firms employing non-union men. In return the union agreed not to work for any firm which refused to join the Association or for a wage lower than set forth in the contract, thus helping to stabilize employer costs and assisting employers in forcing other firms to join the Drayage Association. This agreement tied the union and Association together in a mutually convenient effort to stabilize competition within the industry (Knight 1960:58-60).

Founding of the City Front Federation, Early 1901

Waterfront workers in San Francisco had often been divided, with various jurisdictional disputes causing conflict, especially between the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific and the several longshoremen’s unions. Recognizing that disunity among workers handed a powerful weapon to the bosses, in the fall of 1900 the Sailors and Longshoremen signed an agreement that not only delineated lines of jurisdiction in cargo handling, but also established a policy of mutual assistance by specifying that members of these unions would not cooperate with nonunion workers in receiving and discharging cargo. This led to an even stronger alliance, when in early 1901, a federation of all onshore and offshore waterfront unions, including the Teamsters, was formed. Called the City Front Federation, it was a labor body with formal, centralized authority. Its constitution authorized its president to order a strike vote of all member unions if an employer offensive made it “...necessary to order a general strike” (Knight 1960:61).

By the summer of 1901 the City Front Federation included fourteen unions, between 13,000 and 16,350 members, and had a treasury of $250,000 (Knight 1960:61; The San Francisco Examiner July 21, 1901:18). The Federation was anchored by the Sailors, the Teamsters and four longshoremen’s unions, but also included a number of smaller unions, such as the marine firemen, porters, packers and warehousemen, ship repair craftsmen, and harbor workers. Together they could largely control the transportation and commerce of San Francisco and therefore had formidable power to choke off the city’s economic life and force employers to recognize and negotiate with their unions.

The Founding of the Employers' Association , April 1901

Employer organizations of various types had existed in previous decades in San Francisco, but had become inactive. With unions growing more powerful in 1900 and 1901, the key capitalist businessmen of San Francisco concluded that they should organize a counteroffensive to roll back and destroy the growing democratic power that unions represented. In April of 1901, fifty militant employers formed a secretive organization known as the Employers' Association. The organization was to serve as the guiding anti-union body for the San Francisco ruling class. To make sure that ample funds existed to carry out their policies, each pledged $1,000 to the organization. As other employers joined, they were also required to post bonds as guarantees of their observance of the Association’s policies. In this way the anti-union strike-breaking fund of the bosses grew to an estimated $500,000 (Knight 1960:67).

Although a semi-secret organization, the Employers’ Association is estimated to have had a membership of over 300 firms, with influence over many more. The Association exercised centralized control over its member firms, forbidding any member from granting a union demand or settling any labor dispute without the express consent of the association’s executive committee. Table 11-1 lists the members of this executive committee, along with their key corporate connections.

| Member | Corporate Connection |

| Frederick W. Dohrmann Jr. | Secretary, Nathan, Dohrmann Company |

| A.A. Watkins | Vice President, W.W. Montague & Company; President San Francisco Board of Trade |

| Charles Holbrook | President, Holbrook, Merrill & Stetson; a director of United Railroads, San Francisco, Union Trust Company and the Mutual Savings Bank |

| Harvey D. Loveland | Vice President, Tillmann & Bendel |

| F.W. von Sicklen | Dodge, Sweeney and Company |

| Percy T. Morgan | President, California Wine Association; a director of California Fruit Canners Association |

| Isaac Upham | Payot, Upham and Company |

| Frank J. Symmes | President, Thomas Day Company, President of the Merchants Association; a director of Spring Valley Water Company and Central Trust Company |

| Edward M. Herrick | President, Pacific Pine Company and Grey’s Harbor Commercial Company |

| Akin H. Vail | Sanborn, Vail and Company |

| Joseph D. Grant | Murphy, Grant & Company, a director of Donohoe-Kelly Banking Company, Mercantile National Bank, Mercantile Trust Company and Natomas Consolidated |

| Jacob Stern | First Vice President of Levi Strauss & Company, a director of the Bank of California, Union Trust Company and North Alaska Salmon |

| S. Nickelsburg | President, Cohn, Nickelsburg & Company |

| Adolph Mack | Mack & Company. Also a director of City Electric Company |

| Andrew Carrigan | Vice President, Denham, Carrigan & Hayden Company |

| Henry D. Morton | Morton Brothers |

| J. S. Dinkelspiel | J.S. Dinkelspiel & Company |

| George D. Cooper | W. and J. Sloane & Company |

The Employers' Association was representative of the highest economic circles of San Francisco, with close ties to the Board of Trade, Merchants Association and many of the biggest and most important firms of the city. The presence of direct connections to United Railroads, the Spring Valley Water Company and the Bank of California, as well as several other leading banks, is especially telling, for these were among the largest and most powerful corporations in the state. Its one weakness was that it had no direct ties to what was by far the single largest and most powerful corporation of the time, the Southern Pacific Railroad. Based in San Francisco, the railroad would be affected by the developing class struggle and also had the most influence with Governor Henry T. Gage, who had served as one of its attorneys. Despite the absence of the SP, the Employers' Association was nevertheless an organization by and for leading ruling class circles of San Francisco. It could also be confident in the support of the mayor and city administration, due both to the natural tendency of capitalist government--Democratic or Republican-- to side with big vested interests and because the Democratic Mayor, James D. Phelan, was also a leading capitalist and had served on the same corporate boards of directors as some of the executive committee members.

'The Labor Council and Industrial Disputes in Other Trades

The San Francisco Labor Council had been founded in late 1892 with 34 affiliates. Although it had been on the decline during the next few years due to employer attacks and internal conflict, it revived after mid-1897. From then on, with business conditions improving, it grew rapidly (Knight 1960:31, 36). By early 1901 the Labor Council, led by Ed Rosenberg and W. H. Goff, had become a real force in San Francisco. Its efforts to organize all workers, regardless of skill level, made San Francisco preeminent among major American cities in the degree of unionization among less skilled workers. Unfortunately, this positive effort resulted in a division in labor’s ranks when the craft union oriented Building Trades Council, led by P.H. McCarthy, broke with the Labor Council, openly scorning its efforts to organize unskilled, more easily replaced workers (Knight 1960:63-64). Some of the individual unions that made up the Building Trades Council later supported the City Front Federation in its conflict with the Employers Association, but most did not, violating a key labor principle held by the more advanced elements of the labor movement, the need for solidarity and unity among workers and their organizations.

Other unions were also on the move. In May of 1901, conflicts broke out in both the restaurant and metal trades industry. More than a thousand restaurant workers struck for the ten hour day and 4,000 to 5,000 workers in the metal trades struck for the nine hour day. Other unions supported both strikes, but the Employers’ Association intervened in these conflicts, strengthening the will and the resources of the employers involved. Both strikes eventually fell well short of their goals, even though the strike in the metal trades went on for about ten months (Knight 1960:67-71, 90-91).

The Teamsters Locked Out, Mid-July 1901

With the lines of battle between organized capital and organized labor more and more sharply drawn, and neither side willing to budge from basic principles, it did not take much to set off a new and more explosive conflict. The spark was a seemingly small and unimportant dispute over handling the baggage of a religious group arriving in San Francisco to hold a convention. The Morton Special Delivery Company, a non-union firm, which did not belong to the Draymen’s Association, was to handle the baggage. It had, however, subcontracted part of the job to a firm that was part of the Draymen’s Association, but had union workers. Moreover, the Morton firm’s owner, Henry Morton, was a vigorous opponent of the Teamsters’ Union (The San Francisco Examiner July 21, 1901:18; Knight 1960:72). The Teamsters Union, therefore, decided not to handle the baggage, which was justified by their contract with the Draymen’s Association, which said that union drivers were to reject employment by non-union firms. The union not only wanted to foster the union shop in transportation, but also to push back against the strongly anti-union attitude of Morton Special Delivery. As Michael Casey put it: “We stand by the proposition not to work for or with those who have shown an unfriendly spirit toward union men. We stand by that resolution” (The San Francisco Examiner July 20, 1901).

The Draymen’s Association (and behind it the Employer’s Association) felt the Teamsters’ Union had to be challenged and crushed, and now they had an excuse. It said its agreement with the Teamsters would be rendered null and void if the Teamster members did not handle what Casey had labeled “hot cargo”. They began to dismiss and lockout all Teamsters who refused to obey the orders of their respective bosses to handle the baggage for Morton Special Delivery. The Draymen’s Association began to hire scabs to take the places of ousted workers and took a stand amounting to an ultimatum to the Teamsters: “quit the union or lose your job”. The Draymen were pressured to take this stand by the Employers’ Association, which reportedly met with the Draymen specifically on this issue (The San Francisco Examiner July 21, 1901: 18). Within a few days almost 1,000 Teamster’s Union men had been dismissed from their jobs, locked out because they refused to handle the “hot cargo” (The San Francisco Examiner July 23, 1901:1).

During the first few days, the Teamsters’ played a waiting game to see how things would develop and to put the responsibility for a wider strike upon the shoulders of the employers, while beginning notifications and discussions with their allies in the City Front Federation. Jefferson D. Pierce, Pacific Coast organizer for the American Federation of Labor, visited Teamster headquarters and, after appraising the situation, telegraphed President Samuel Gompers about the lockout. Meetings were held with the Sailors Union of the Pacific and representatives of the City Front Federation, but no decisions were made. Union pickets were sent to various key locations to watch and intercept any non-union drivers, explain the situation to them, and try to influence them to join the union. This tactic was successful in at least one instance when non-union drivers, reportedly imported from Benicia, gave in and returned their teams to the stables (The San Francisco Examiner July 22, 1901:2, July 23, 1901:2).

At this point in the developing situation, the Coast Seamen’s Journal, the organ of the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific, published a powerful editorial in support of the teamsters, warning the entire labor community of the likely result of the actions of the employers. The editorial began by pointing out:

...There was but one thing left for the Teamsters to do, and that they promptly did; they refused to do the work of the non-union concern. At this juncture the Employers’ Association showed its hand in the matter. The Draymen’s Association, against its will, as it appears, had been forced into the secret order of industrial assassins, and acting upon the mandate of that body the Draymen notified their employees that they must either “quit the union or quit their jobs.” This was a deliberate challenge of the Teamsters’ right to maintain their organization; it was a challenge dictated in the spirit that has all along characterized the Employers’ Association and its predecessors--the spirit of war and destruction to trade-unionism...Should the trouble spread, as it undoubtedly will if the Employers’ Association has its will...the result to this city and port may be better imagined than described. The Brotherhood of Teamsters may be depended upon to make the fight interesting for its opponents. Behind the Teamsters stand a large number of fellow trade-unionists who may also be depended upon to make a good run. It looks as though the crucial point in the conflict between the Employers’ Association and Organized Labor has been reached. There is but one way that we can see at present in which an upshot of far-reaching effect upon the city can be forestalled, and that is by a counter organization, tacit or formal, of press and public to offset the inequitable and desperate policy of the Employers’ Association. The only question at issue is as to whether or not men have the right to organize for their own protection and to hold their employers to the agreement made with them. The press and public can settle this question quickly and effectually. Unless they do, they will be responsible for whatever may happen as a consequence of leaving it to settlement by physical demonstration (Coast Seaman’s Journal July 24, 1901:6).

Police and City Government Side with the Employers

Late July saw a new development, the decisive intervention of Mayor James Phelan’s administration on the side of capital by detailing large numbers of police to help strikebreaking scabs destroy the union. Already by late July of 1901 over one half of the city’s police force, 300 out of 588 men, was detailed to protect the strikebreakers (The San Francisco Examiner July 27, 1901:3; September 26, 1901:12). This was initially done at the behest of the Draymen and not due to any need to protect law and order. On July 24 George Renner, the Manager of the Draymen’s Association, was quoted in The San Francisco Examiner: “...We have had mounted police and patrolmen detailed to accompany the teamsters who are at work, not because of any overt act, but because prevention is better than cure. It will take some time...to fill the places of all of the men who have refused to obey orders; but it will be accomplished in time...” (The San Francisco Examiner July 24, 1901:4).

City police were stationed on wagons (called “trucks”), driven by scabs, to act as guides and even drivers for those strikebreakers who did not know the city and to try to prevent union pickets from convincing them to join the union. Police not only acted as escorts for scabs, they even sometimes even called for them in the morning at their homes and accompanied them home at night (The San Francisco Examiner July 28, 1901:19). This almost immediately led to conflict, with police squads attacking and beating union men in union dominated neighborhoods in the south of Market area, which led to retaliatory violence against the strikebreakers by angry members of the local working class community. The San Francisco Examiner vividly described several incidents on July 25:

In the morning at 8 o’clock three non-union drivers were leaving C. B. Rode & Co.’s barn on Bryant Street, near Fifth, with trucks and the police requested the union pickets to leave the teamsters alone. The pickets argued the matter and in the meantime a crowd of union sympathizers, numbering about 300, collected. The manager of Rode & Co. telephoned to police headquarters and Captain Wittman, with a score of policemen, hurried to the scene. Wittman ordered his men to charge the crowd with clubs. The union men say the crowd was orderly and that the pickets were conducting themselves within the law. Four or five men were badly clubbed by Wittman and his squad. The crowd quickly dispersed. One of the drivers decided to join the union; the other two drove on with policemen on the trucks to protect them while going for loads. In the afternoon about 4 o’clock the union sympathizers gathered in large numbers at Sixth and Folsom streets. A truck owned by McNab & Smith came along Sixth street...The crowd closing around truck forced the horses...into the depression on one side of the street...The crowd hooted and tried to persuade the driver to leave his seat. Some one threw a stone, which hit him on the back of the head. That decided him and he made a break through the crowd to get away...Two more teams, belonging to the same firm, came along and the crowd speedily persuaded their drivers to join the strike...a policeman drove the dray down to the depot...The crowd soon gathered again and Sergeant Campbell and eighteen men were sent to disperse the gathering, which they did with some display of force (The San Francisco Examiner July 25, 1901:3).

These events apparently led Teamsters’ Union leaders Michael Casey and John McLaughlin to call out on strike almost all of the remaining union teamsters. By the next morning a total of 1500 men were locked out and on strike (The San Francisco Examiner July 25, 1901: 3).

With even more angry teamsters on strike, the confrontations between the local community of unionists and their supporters and scabs imported by employers from as far away as Bakersfield and Los Angeles quickly grew larger and more threatening. Police, who actively supported the bosses by protecting scabs, also were even more involved. The San Francisco Examiner reported on July 26:

About 6 o’clock last night a crowd of union sympathizers attacked a non-union driver on one of McNab & Smith’s trucks at Bryant and Third streets. There were about thirty boys and a number of men, Policeman Porter was on the truck. Rocks were thrown and an effort was made to pull the non-union driver from his seat. A crowd quickly collected and in a couple of minutes there were fully 500 people about the truck

...Policeman Porter drew his club, but he could do little with it, because the crowd closed in on him. Policemen Harrison, Eastman and half a dozen others from the Southern station who were in the district, learned of the trouble and charged on the crowd with clubs. The crowd kept increasing until there were more than 1,000 people on the street. Rocks and other missiles were hurled at the truck. Policeman Porter was struck on the left leg and injured. A rock also struck Policeman Harrison. The patrolmen cracked a number of the more aggressive men with their clubs.

As fast as the policemen cleared a way more men closed in on them. Fully twenty men were struck with the clubs of the officers before the truck was again started for the stables.

The crowd followed at a distance and continued to hurl stones at the policemen and the non-union driver finally got his load to the barn at Eighth and Brannan street. Policeman Porter will be incapacitated for duty by reason of the injury to his leg...

In the same neighborhood one of the trucks of McNab and Smith that are used to carry fruit for the California Cannery Company was disabled. A nut had been removed from one of the front wheels, and, without any warning, it came off, scattering fruit all over the street. Cannery hands were called out to carry the fruit into the sheds. The crowd became large and troublesome and began hooting the cannery employees. Sergeant Christensen, assisted by Policemen Hook and Burdette, charged the onlookers, who soon dispersed (The San Franicsco Examiner July 26, 1901:3).

More incidents illustrating that a community rebellion against the injustice of scabs and police trying to destroy the Teamsters union was underway followed on the next day:

Thomas Bryan, a Petaluma teamster, hired...by McNab & Smith, was seriously injured while on his way to supper by strike sympathizers on Thursday night. Bryan had both arms broken and was otherwise hurt...Policemen Peshon and P.L. Smith drew their revolvers and dispersed a crowd of men at Second and Folsom streets who had attacked the driver of a team...In a clash which occurred between the police and a crowd at Sixth and Folsom, John Ely, a teamster...received a severe laceration of the scalp from a club in the hands of Policeman Max Fenner...In a disturbance which occurred at Fifth and Bryant streets last evening, Adolph Thiler, a cabinetmaker...was badly beaten by Policeman Peter J. Burdette...Over 300 policemen are at present engaged in protecting the interests of the draying firms against their striking employees. All available men have been called to do actual police duty and are detailed either as convoys to trucks and teams or are patrolling the districts where trouble is most likely to arise...(The San Francisco Examiner July 27, 1901:3).

The Employers’ Association’s Ultimatum

The situation was still developing at the end of July when the Employers’ Association pressured various San Francisco capitalists to force their workers to choose between their union or their jobs. As The San Francisco Examiner (July 28, 1901:19) reported:

In many business houses yesterday the proprietors summoned their employees and put the question squarely to each one: “Will you take orders from us, or from your union?” On the answer hung the option of further employment. Those who elected to stand by their labor organization were “given their time” -- that is to say, were paid off and dismissed. Those who chose to remain at work were required to write out their resignations from the union.

The workers at the various San Francisco beer bottling establishments were presented with this ultimatum, as were workers at local box manufacturing factories and many members of the porters and packers union. Most of the affected workers stayed with the union and went on strike. It was clear to all that the Employers’ Association was behind this demand:

Inquiry among the employers at the different beer-bottling establishments led conclusively to the decision that their action had been prompted by the Employers’ Association and foreshadowed the steps taken by other employers yesterday in asking men to choose between their labor organizations and their employment...The employers made no secret of the fact that their action was concerted and the result of an understanding had in the Employers’ Association... (The San Francisco Examiner July 28, 1901:19).

San Francisco and Bay Area Unions Prepare to Fight

With the situation reaching a crisis point, the San Francisco Labor Council gave its executive committee power to take any necessary defensive or offensive steps against the “arbitrary action of the Employers’ Association.” It also adopted a resolution which read in part as:

Whereas, Organized labor of San Francisco and vicinity now finds itself menaced from every quarter by a secret body known as the Employers’ Association, with the purpose of destroying the trades unions, thus denying the members thereof the right to combine for their own protection...and

Whereas, The trades unions have now and at all times in the past executed every possible means to insure amicable relations between employer and employee, and in event of dispute to bring about a restoration of harmony by conference, conciliation and concession, and

Whereas, The Employers’ Association has persistently rejected these steps and now seems determined to pursue its policy of strife and destruction...and

Whereas, The dangerous and unlawful motives of the Employers’ Association are proved by its actions in forcing, by threats of retaliation and ruin, employers who are well disposed toward their employees...

Resolved, That, until said Employers’ Association makes formal declaration of its purposes and official personnel, it shall be regarded as having no legal right to exist and as having no claim to recognition...

Resolved, That the San Francisco Labor Council pledges itself, and urges a like declaration by each of its constituent bodies, to stand firm to the principles upon which we are organized, the first of which is the right of the workers in all callings to combine for mutual help as individuals and as organizations...

Resolved, That we reaffirm our position as favoring the adjustment of all existing and future disputes by means of conference between the parties involved...failing acquiescence in this proposal by the employers concerned, the responsibility for the continuance or expansion of the present strikes, lockouts and boycotts must be laid upon that party which has proved itself unapproachable to reason and… to the appeals of common humanity (The San Francisco Examiner July 27, 1901:3).

Final Attempts to Conciliate Fail

True to their principles and word, the highest level representatives of San Francisco’s organized working class--the Labor Council, the City Front Federation, and the Teamsters--were ready to meet and discuss the adjustment of any and all disputes with all appropriate parties. On the afternoon of July 29, even in the face of the blatant and continuous police aid given to the employers, they conferred with Mayor Phelan, the Municipal League’s “Conciliation Committee”, and some business representatives at the Mayor’s office to try to reach a compromise. True to form, the Employers’ Association refused to attend and meet with labor; the Mayor had to take labor’s proposals to the headquarters of the Employers’ Association in the Mills Building. After meeting with the leaders of the Employers’ Association, the Mayor came away without an agreement even to start negotiations, only a response in the form of a letter from M. F. Michael, the Associations’ attorney. The essence of this letter reprinted in full in the Examiner, was contained in the following paragraph:

I am instructed by the Executive Committee of the Employers’ Association to advise you that the proposition thus submitted appears to the association not to present a satisfactory solution of the present difficulties; furthermore, that the association is of the opinion that an agreement in the shape proposed could not be adequately maintained or enforced (The Examiner July 30, 1901: 2).

It was clear that the organized employers wanted total power over the workers. The exercise of such power was a main cause of the alienation that the workers had felt and were rebelling against. Collective power in a union gave the workers a feeling of wholeness and freedom they could gain no other way. As Sailors’ Union of the Pacific’s leader Andrew Furuseth commented to the press after the meeting:

It is not the unions that are bringing this upon the city. The employers ignore us entirely...they will not recognize our committees or delegates or agents. They are willing to give the individual employment, but they are determined to crush the unions. They had no representatives at this afternoon’s meeting in the Mayor’s office, and of course there could be no results (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1).

The lines were now drawn in the sand; it was up to working people and their leaders to act.

July 30, 1901: General Strike on the Waterfront

Immediately following the conciliation talks, the leaders of the City Front Federation called a meeting for that same evening, July 29. All the issues involved were carefully and thoroughly discussed, and it was not until about midnight that the following decision in favor of a general strike of all member unions was made:

Resolved, That the full membership of the City Front Federation refuses to work on the docks of San Francisco, Oakland, Port Costa and Mission Rock and in the city of San Francisco, but that the steamships Bonita and Walla Walla, which sail tomorrow morning, and which have booked passengers, be allowed to go to sea with the union men of their crews (The San Francisco Examiner July 30, 1901:1).

While the leaders were deliberating, mass gatherings of rank and file members were organized all over San Francisco, and, as the night wore on, these union members were anxious for news. About 600 members of the Brotherhood of Teamsters were assembled at the hall of the San Francisco Athletic Club at the corner of Sixth and Shipley streets. When Michael Casey arrived after midnight and announced that the City Front Federation was calling a general strike on the waterfront :

... a scene of the wildest enthusiasm ensued. Cheer after cheer was given. Since the inception of the strike the teamsters have been compelled to fight the merchants and bosses single-handed, and it was generally admitted that the strikers would be ignominiously defeated unless other unions rendered immediate assistance. Thus the men had come to look on the City Front Federation, embracing the strongest combination of united labor on the Pacific Coast, as their most desirable ally.

After Business Manager Casey announced the decision of the City Front Federation, the Brotherhood of Teamsters decided by a unanimous vote to fight the strike out to the bitter end without regard to the cost or consequences. The brotherhood has in all almost 2000 men now on strike (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1).

The scene at California Hall, where the members of the Porters, Packers and Warehousemen waited for word, was no less dramatic. The 2000 members of this union were

...unanimous in wishing that a general strike would be ordered and could not understand why the men of the city front could not come to the same conclusion without the necessity of a lengthy session...The guard at the door of the union’s meeting place was the first man to receive the news. When he opened the door and announced to the anxiously waiting laboring men that their wishes had been granted and that on the morrow 16,000 men would quit work and enter the ranks of the strikers and the locked out men the cheers were deafening. The men yelled themselves hoarse, for the announcement of the general strike meant that their fight was to be made the fight of every laboring man in this city (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:7).

Similar “tumultuous cheering” took place once the decision to strike was announced at the mass meetings of the Sailors’, the four Longshoremen’s locals and other interested unions (Coast Seamen’s Journal July 31, 1901:11). Speaking before hundreds of sailors at their headquarters, Andrew Furuseth said that the “employers are determined to wipe out labor unions one after another...There is no other way of having peace except by fighting for it” (Knight 1960:77). The organized workers of San Francisco were practically unanimous on the need for a general strike on the waterfront to counter the attempt to crush their unions (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1).

There were ten striking unions with an approximate membership of 16,000 men.

| Union | Number of Members |

| Sailors’ Union of the Pacific | 4,500 |

| International Longshoremen’s Association (four branches) | 4,500 |

| Brotherhood of Teamsters | 2,000 |

| Porters, Packers and Warehousemen | 2,000 |

| Pacific Coast Marine Firemen | 1,500 |

| Marine Cooks and Stewards | 700 |

| Piledrivers and Bridge Builders | 300 |

| Ship and Steamboat Joiners | 300 |

| Coal Cart Teamsters | 200 |

| Hoisting Engineers | 75 |

| TOTAL | 16,075 |

On July 30, these unions, organized as the City Front Federation, issued a statement on the causes of the strike, asserting the rights of the working class against “arrogant capital”:

Having closely watched the trend of affairs throughout the country and being cognizant of the policy of the employers, which is to disrupt labor organizations...the Federation claims the right for its members to organize for their mutual benefit and improvement... we further claim the right to say how much our labor is worth and the conditions under which we will work. The Employers’ Association, composed of the principal importing and jobbing concerns of this city...have tried with more or less success to destroy some of the smaller organizations, and as their minor successes gave them confidence they reached out further with the idea that ultimately their plan would be successful...In view of the fact that the teamsters were locked out the Federation found it absolutely necessary to take action...The Federation has exhausted all honorable means to have the difficulty adjusted...and finds that there is nothing left but to appeal to its membership to be true to the cause for which organized labor stands...we are satisfied that we have done everything we could to avert this crisis, but arrogant and designing capital willed it otherwise. Those individuals in society who would use their industrial power to rob us of our right of organization...must bear the responsibility for whatever may now take place (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:1). The strike’s aim was to economically punish the employers in order to put irresistible pressure on the Employers’ Association to agree to negotiate a fair settlement which preserved and enhanced union power. Andrew Furuseth, secretary of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, was elected chairman of the strike committee. He said at the outset that: “We have dallied long enough with the Employers’ Association... our action will teach them that we mean business. Every man is determined and the sooner the association appreciates this the better it will be for them and the business interests of this city and vicinity. All the talk has been done -- this is action” (The San Francisco Call July 30, 1901:7).

The all-out battle for the union rights of working people and against the Employers’ Association was underway.

The Strike Leaders: Furuseth and Casey

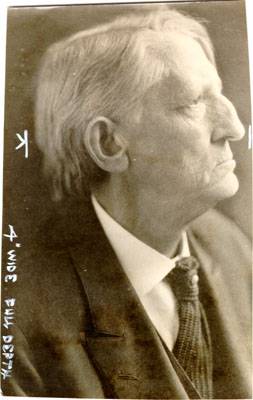

Andrew Furuseth, 1928

The top leadership for the strike was lodged in the persons of two men: Andrew Furuseth of the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific, who was Chairman of the Strike Committee, and Michael Casey of the Brotherhood of Teamsters, who was President of the City Front Federation. Furuseth had been a leader of the Sailors almost from the founding of this union in a torch-lit meeting on the Folsom Street wharf on March 6, 1885. The militant unionism of Furuseth and the Sailors’ had developed out of the exceptionally abusive system developed by the shipping companies, boarding house owners, and ship captains, who had long worked together to keep the individual sailor in a state of perpetual indebtedness and semi-slavery. The strong feelings of injustice, the constant conflict with the bosses, and the rough and tumble brotherhood of the sea led to a special commitment to worker solidarity and class struggle on the part of the Sailors’. It was the visionary unionist and utopian socialist Burnette G. Haskell who had pleaded the sailors’ cause on the Folsom Street dock in 1885, but it was the 2,000 militant sailors who immediately joined that made up the solid foundation of what already by 1901 was a union seeped in struggle. The Sailors’ had to constantly be ready to battle, because the capitalists, the captains and the boardinghouse owners never gave them a rest. On August 7, 1901 the Coast Seamen’s Journal published its call to battle in an editorial entitled “The Old Guard in Front” recalling the many bitter fights for the survival of their union:

...Fortunately or unfortunately...the Sailors have never had peace enough with their masters to allow of their growing fat and lazy. The present generation of the Union has been born to a heritage of trials and hardships, not so severe perhaps as those encountered by the men who founded the organization, but yet severe enough to call forth the best energies of every member. It should be in every man’s care to see that he lacks in nothing to uphold the prestige of the Sailors’ Union and to honor the memory of the men who fought to establish it on its present firm foundation.

The unanimity and enthusiasm shown by the seamen at the call of duty is proof of a spirit that counts no sacrifice too great in defense of principle. At the same time, it is well to reflect that it was only by such sacrifices in the past that the Union was rooted deep in the soil, and thus enabled to withstand the desperate assaults made upon it from time to time. Of the old Union boys who met on Folsom Street Dock in San Francisco on March 6, 1885, and dedicated the organization to everlasting life and glory, who carried its banner so high through all the dark days and years that followed, that its folds caught the light of heaven through mist and murk -- of those men, some are with us still, others are scattered throughout the world spreading the fame and lesson of the Union they helped to form, while still others have passed into line with the undying dead whose memory inspires the world’s greatest deeds for humanity. No member of the Sailors’ Union, standing to-day upon the verge of a conflict that, no matter what comes, will mark the greatest epoch in the history of the Union, but must feel...as men always feel when they go into a clean fight for a good cause -- that victory cannot fail us except by chance... In this fight ... the line is clearly drawn between the two great forces, the labor movement and the Employers’ Association.

Every man, then, may feel that when he strikes, his blow will tell in the right spot.

Comrades, remember the past of our grand old Union and be true to its traditions!The labor movement and the lovers of humanity on the Pacific Coast, throughout the United States and the world, are watching and waiting upon us. The Union is our shield in peace and war. Let us take it up and say, as did the Spartan mother to her boy: “With it or upon it!” (Coast Seamen’s Journal August 7, 1901:7).

Like many of his fellow union members, Andrew Furuseth was an immigrant, and was both completely devoted to his union and stoically uncompromising toward its enemies. Unlike many of his mates, he was intellectual and solitary. When threatened with a jail sentence for strike activity he told an interviewer that he was not afraid of a jail cell, since: “They can’t put me in a smaller room than I’ve always lived in, they can’t give me plainer food than I’ve always eaten and they can’t make me lonelier than I’ve always been” (Chiles 1981:5).

Furuseth expressed his philosophy about the labor movement, how it was a freedom movement for the worker, and the requirements of his time as follows:

The labor union of to-day is really a powerful bulwark of liberty and a mighty aid to the advancement of civilization. This sounds large, I know, but the claim is none too large. It encourages the workingmen to a feeling of oneness with their fellows—a feeling that promotes gentleness in their relations with one another, both in sickness and in health. It teaches men to study their condition in the world... and it leads them to struggle the harder to move upward. It has a strong influence toward counteracting dangerous tendencies toward political and industrial absolutism. And finally, it is a preventative of that degree of competition which makes for social regression. Without labor organizations the competition of laborer with laborer would have full play, and full play would be ruinous with capital selfish as capital always has been and always will be. Unchecked competition in the labor world means a gradually sinking standard of wages, causing a gradually sinking standard of living—less of comfort, less of leisure, less of light, less of sweetness, more of barbarism. Combinations of capital must be met by combinations of labor, or there will be an increase of servility, an increase of poverty among the masses, and diminishing manhood and womanhood (The San Francisco Examiner August 1, 1901:1, 8).

In 1901 Michael Casey of the Teamsters’ Union was a no less impressive figure, as The San Francisco Examiner reported :

Mr. Casey is thoroughly representative of the great class of which he is a leader. He is a toiler, and has been one since childhood. His tall, muscular form says work: his determined blue eyes and his bronzed seamed face say work: his manner of carrying himself says work. He is forty years of age and looks older; he is a native of Ireland, but has spent all save the few opening years of life in the United States, and most of his boyhood and all since then in California; and gained an education in the public schools and a private business college of this city. He has a wife and six children, and is dependent on his personal earnings for a livelihood.

You couldn’t help feeling friendly to Casey, no matter what your interest might dictate; for there are honesty and kindliness in his deep-set blue eyes, and there’s earnestness in every line of his rugged countenance.

He feels that the present strike is a symptom of a widespread condition, and that it is very much more significant and vastly more important than is generally believed. He does not merely talk this way, understand -- he FEELS it; and when he speaks on the subject his voice vibrates with sincerity...

“It has seemed to us recently that a considerable number of the heavy employers in San Francisco have determined to crush the labor unions. Indeed in some cases within the last two weeks there have been open declarations obliging men to choose between membership in the unions and retention of their employment. Under the circumstances the only rational course open to us has been to stand for the principle attacked, even at the cost of an extensive strike...”

He interprets the attitude of California capitalists as sympathetic with the attitude of capitalists in the greater money centers... “There is a tremendous change in process” he said, looking thoughtful and serious. “A man can’t consider the recent centralization of capital in the other States without something of a shiver, if he is a breadwinner. Every day narrows the freedom of individual capitalists and substitutes a new centralization of power. The formation of the Billion Dollar Steel Trust is really one of the most threatening signs of modern times -- and only a sign, mark you, a sign of a sweeping tendency.”

Against the steadily centralizing sway of capital, he feels that labor must offer a steadily unifying front. The labor unions he regards as a necessity for the preservation of freedom as we now understand freedom... he has a pretty definite notion that capital as capital is “void and empty from any dram of mercy.” His own strength and the co-operation of men in his own walk of life are THEIR safeguards he concludes.

“The working classes must stick together,” he observed. “When their unions are assailed they must resist. Unless they do, there will be a gradual sinking backward into the conditions out of which we have struggled.” (The San Francisco Examiner August 1, 1901:1, 8).

As immigrants from Scandinavia and Ireland respectively, Furuseth and Casey were representative of the unions they led, and this fostered group solidarity. In 1900 boatman and sailors made up the fifth largest male occupation in the port city of San Francisco, and by far the largest group of boatmen and sailors, (38.2%), were from Scandinavia. United States born workers made up only 12.1% of San Francisco’s boatmen and sailors, the rest were immigrants, with the Scandinavians dominant. In 1900 draymen, hackmen and teamsters made up the seventh largest male occupation in San Francisco, and immigrants from Ireland were by far the largest group, making up 36.4%. United States born workers made up only 20.6% of San Francisco’s draymen, hackmen and teamsters in 1900; the remainder were immigrants (computed from data in United States Census Bureau 1904:720-723).

Scabs and Conflicts

The core strategy of the capitalists was to break the strike through the massive use of scab labor. But on the day before the general strike on the waterfront was declared, The San Francisco Call announced that seventy-two non-union teamsters, whom the Draymen’s Association had recruited from Bakersfield to help break the Teamsters’ Union, had exited the city to return to their homes. They had been convinced of the justice of the union cause, no longer wanted to be scabs, and even had become union men! As the Call (July 30, 1901:7) reported: “...Before departure most of them had been won over to the side of the brotherhood and had been made honorary members. Although they had come in passenger cars at the expense of the Draymen’s Association, they were shipped back in a freight car attached to a Santa Fe freight train...”

The loss of these men, and no doubt many more who left individually or in smaller groups not reported by the press, put the bosses in a bind; the unions were successful in convincing large numbers of men not to scab on the strike, threatening the rapid defeat of the Employers Association. It therefore began to send out employment agents to recruit strikebreakers from groups among the population who had fewer reasons to be in solidarity with unions: men and boys from farms and smaller interior towns, soldiers returning from the Philippines, students from University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University, Chinese, Filipinos, and African-Americans from as far away as the Midwest. The use of people of color as strikebreakers had long been a common and reprehensible tactic of the bosses to divide the workers, break their solidarity, and get them fighting among themselves. Unfortunately, workers too often fell into the trap of supporting white supremacy and established discriminatory, all white unions. Banned from membership by almost all AFL unions, African-Americans and other people of color often had very little incentive to refrain from strikebreaking against those who refused to welcome them into the American labor movement (Knight 1960:79).

The use of African-American strikebreakers led, on the very first day of the general strike, to the first of what were to be many shootings, most of them by non-union men who were carrying guns. The employers also had well connected attorneys ready to defend scabs who engaged in violence. The Examiner reported on the incident:

Roscoe Horn and William Ferguson, non-union teamsters, fired eight shots into a crowd of strikers yesterday at Eleventh and Harrison streets. They are colored men employed by G.W. Emmons & Co. draymen. Patrick Lynch, a union teamster, residing at 351 Eleventh street, was wounded in the hip by one of the shots... In telling the story of the affray Ferguson said: “ Horn and I were on our way to work when at the corner of Eleventh and Harrison streets we were met by a gang of teamsters who yelled at us and then began throwing stones. I drew my revolver and fired a shot in the air to scare them. A crowd that was at Eleventh and Bryant streets was attracted by the report and came towards us. We were between two mobs and they began throwing stones. We then fired directly at them and they scattered. I fired five shots and Horn three. We then made our way to the stables.”

Sergeant Campbell stated that the crowd was threatening in its attitude and a non-union teamster had been beaten only a few moments before. Lynch, the wounded man, stated that he had no intention of molesting the men, but was walking across the street when he was struck.

Both Horn and Ferguson were released from custody on $100 cash bail. Bond Clerk Greeley says he fixed the bail at that small sum on the assurance of Attorney Joseph Coffey that it was an unimportant affair...Attorney Coffey has been retained to defend non-union teamsters who get into trouble. Lawyer Coffey is the attorney for Chief of Police William P. Sullivan and the Chinese gamblers (The San Francisco Examiner July 31, 1901:2).

Over the next few weeks numerous similar incidents were reported in the newspapers. Below is a sample of events, that illustrate a number of characteristics of the strike, including several shootings and near shootings and the strong support that the workers had among the mass of the people, many of whom were outraged at the scabs and the police who helped them, and who were becoming more and more engaged in what was becoming a community rebellion for the freedom to organize and defend collective working class rights:

For twenty minutes yesterday, between 4 and 5 o’clock, traffic was blocked on Market street at the crossing of Third by a truck belonging to Farnsworth & Ruggles, draymen, and driven by a non-union teamster.

The truck was heavily loaded with boxes and the day was hot. The asphalt pavement in spots had assumed the consistency of mucilage and in front of Lotta’s fountain one wheel settled and stuck fast. The truck was anchored and the driver did not seem to know enough to get out of the hole. The other wheels of the truck rested on the car tracks...

The crowd was not complimentary.

“Get him out, officer,” they shouted as the policeman, who was acting as escort, took the lines. It was evident that the horses were badly frightened by the shouting and surging crowd.

“Them’s union horses,” remarked a bystander, “and they won’t be driven by any but a union man.”

There were women in the crowd and it was evident that their sympathies were all against the non-union driver.

“Go for him, Jimmy,” shouted one of them, as a young man stepped up close to the driver. “He’s taking the bread and butter out of our mouths, Jimmy, go for him.”

It began to look like a fight... but the police came in with drawn clubs and quelled the fighting instinct. The woman, who had urged on “Jimmy” turned away and, in a disgusted manner, said to a little girl by her side:

“Come along Maggie, let’s go home and make your father’s supper”... (The San Francisco Examiner August 1, 1901:2).C.F. Blair, a non-union teamster, was beaten at Buchanan street and Golden Gate Avenue yesterday morning... As a group of men moved toward him in a threatening manner, Blair drew a revolver from his pocket and began to back away from them. They approached closer, whereupon he pulled the trigger. The cartridge did not explode, and he snapped the trigger repeatedly, but without firing a single bullet at his pursuers. Seeing that Blair’s pistol and cartridges were harmless, they closed in upon him and beat him over the head and shoulders... (The San Francisco Examiner August 1, 1901:2).

John Telford, a non-union teamster in the employ of McNab & Smith, who resides at 100 Park Hill avenue, was ambushed Saturday night...by a gang of unknown men. As he passed a clump of bushes on his way home they made known their presence by firing a volley of stones. Facing his assailants, he drew a revolver...and...fled to the house of Robert Ewing...The stone throwers followed to the door, several displaying revolvers...The situation was critical. Revolvers were flourished in the crowd, stones were thrown and threats were freely made... The approach...of two policemen ...was the signal for the dispersal of the crowd (The San Francisco Examiner August 5, 1901:4).

Attacked by a crowd of strike sympathizers, yesterday morning Henry Davies, a non-union teamster, used a revolver with probably fatal effect. He fired one shot, which struck and seriously wounded Samuel Cole, a teamster who resides at 57 Clara Street. Davies is eighteen years of age... While going to work he was set upon by six men at the corner of Howard street and New Montgomery, nearly opposite his home. He was knocked down and kicked. Upon regaining his feet Davies drew his revolver and fired one shot at his assailants, who ran in every direction. Cole, who was struck, was removed subsequently by his comrades... The bullet entered his left side and penetrated his lungs. He will probably die... (The San Francisco Examiner August 7, 1901: 3).

Wilfred Horton, a non-union colored stevedore, was attacked by strike sympathizers while on his way to work yesterday morning and, after firing his own revolver, was severely wounded in the shoulder (The San Francisco Examiner August 8, 1901:1).

The union leadership counseled against such violence, recognizing that it could backfire, lose the support of public opinion and even bring in the state militia, something the Employers’ Association wanted. Strike Chairman Furuseth stated in a speech on August 8 for example: “If you want us to win this struggle for human liberty you must make a solemn promise to yourself not to allow any one to induce you in any way to break the peace” (The San Francisco Examiner August 9, 1901:2).

On August 21, the Coast Seamen’s Journal, in its review of the situation up to that point in time, made the following comments:

There never was a cleaner and juster fight than that now being made by the trade-unions of San Francisco in defense of a principle dear to every man of intelligence and ambition; if public opinion amounts to anything, as we believe it does; there never was a better chance of victory for labor. If the fight is lost it will be because of the forfeiture of public support, and that can only be caused by an overt act on the part of the strikers, or attributable to them. The conduct of the latter up to the present time is a fair assurance that no such act will be committed in the future except upon provocation beyond ordinary human endurance to withstand. In such event the persons in authority responsible for it will be convicted of a terrible, an indescribable, crime...(Coast Seamen’s Journal August 21, 1901:7).

The employers’ importation of scabs, often by railroad from distant locations, continued throughout the strike, but the unions were able to effectively counter the technique by stationing pickets along the railroad to talk to potential scabs and get most of them to defect to the union even before they got to San Francisco. The unions were aided by the fact that the employers lied to potential scabs about conditions in San Francisco. As a result, many men were recruited into the union cause. African-Americans recruited to be scabs were often successfully invited to join the union cause, and at least one of them, George Smith, became a picket for the City Front Federation, acting as a union delegate to talk to other African Americans to induce them to join the unions and not to scab (The San Francisco Examiner September 23, 1901:4). The Examiner reported:

Seven men of forty-seven recruited at Cincinnati to take the places of the strikers in San Francisco reached the city yesterday and were stowed away on the steamer Colon at the Pacific Mail Dock. Forty men, who said they were induced by misrepresentations to come here, left the overland train at Sacramento. They had listened to the statements of union men who went up the road and, learning the condition of affairs, they refused to take the places of the striking stevedores and teamsters.

The seven men who decided to go to work, one of whom is colored, were brought...to the Long Wharf at Oakland by a special train, guarded by railroad police. From the wharf they were taken to the mail dock by a tug, on which were Sergeant Wolf and a policeman of the San Francisco force...

Agents of the City Front Federation met the Eastern laborers at Reno, and when the train reached Sacramento nearly all the men had determined not to proceed to San Francisco. The gang which left Cincinnati was composed of thirty two whites and fifteen colored men... The colored men were gathered at the levees at Cincinnati...

Curt Hall, President, Presley T. Johnson, Secretary, D.D. Sullivan, Treasurer, and George Ward of the Sacramento Council of Federated Trades, were at the depot on the arrival of the train. They took the laborers to eating houses, where at the expense of the council they were given the only warm meal they had since they left Cincinnati... After their hunger was appeased each man was given a dollar. They were destitute. They were taken to an employment office, where all were furnished employment in Sacramento and on nearby ranches (The San Francisco Examiner September 21, 1901:7).

As stated above, strikebreakers were also recruited from local universities. To try to cut off this source for scabs, W.H. Goff, President, and Ed Rosenberg, Secretary of the Labor Council, addressed a letter to Benjamin Ide Wheeler, President of the University of California, requesting him to prevent strikebreaking activities by members of the university community. Wheeler refused, stating that: “The university is the most important instrument that we possess for preventing the crystallization of society into fixed strata. Let us do nothing to hamper it in the fullest exercise of this, its work” (Coast Seamen’s Journal September 11, 1901:2).

In their response to Wheeler’s justification of the use of students as scabs, Goff and Rosenberg defended the working peoples cause with wit and sarcasm:

...Do you think that a university can prevent the process of crystallization in society? We are only plain workingmen, but we venture to express our opinion that your university education is as powerless to prevent the crystallization of society as it is to prevent the crystallization of primary molecules. This, however, is little to our present purposes. We have a more serious matter than crystallization to consider. We are only anxious to prevent the pulverization of the workingmen, and we ask you if the University of California exists for the prevention of “the crystallization of society into fixed strata,” or is its business to help club the workingmen, who support it, into fixed slaves? We ask for a plain answer, Dr. Wheeler. Please crystallize your verbiage into yes or no. A last word and a plain one: The University is supported by the people of California. It exists by their will, and ought to reflect their ideas...as the people control the revenues we shall have something to say as to what those revenues shall amount to. Be perfectly assured that so long as the University remains what it ought to be, the school of the people, it will have the support of the people. When it becomes an instrument in the hands of the rich to grind the faces of the poor, something is going to happen. What, in your opinion, would be the result if the revenues of the University were to undergo a process of crystallization? (Coast Seamen’s Journal September 11, 1901:3).

Police and Special Deputy Violence

The workers fighting for their rights were up against not only scabs and employers; the forces of the state in the form of city authorities were also always on the side of the employers. Chief of Police Sullivan and head of the Police Commission Newhall, a member of a wealthy landowning family, were completely against unions and the strike. The Police Chief secretly instructed his men to use force to unconstitutionally prevent free association and drive union men off the streets. An Examiner reporter was able to acquire a copy of an extraordinary speech Chief Sullivan made to members of the various police watches on September 5:

I am dissatisfied with the conduct of you men toward the strikers. I have gone about the city and seen my police chatting with strikers. You have neglected your duty by being too lenient with the strikers. I warn you that by so doing you are not carrying out your instructions.

The strikers must be driven from the streets. You must see that this is done. Keep them from congregating on the street corners. Drive them to their homes and see that they are kept there. The strikers must not be allowed on the streets...

If any of you men do not feel disposed to carry out these orders you can send in your resignations and go and join the strikers. I am going to have policemen who obey me...

I do not want you men to speak to any one of what I have said (The San Francisco Examiner September 6, 1901:1).

Acting on the spirit of the Chief’s instructions, members of the police force also went out disguised as longshoremen to provoke trouble with union men on the waterfront, acting as provocateurs to try to incite violence. As The Examiner reported on September 10:

Lieutenant of Police William Price... has been making efforts to obey Chief Sullivan’s order to drive union men “off the earth.” Saturday night Sullivan’s subordinate sent Policeman P.N. Herlihy out in disguise to provoke trouble with union pickets along the water front. Price is in command of the harbor police in the absence of Captain Dunlevy. Without the knowledge or consent of his commanding officer, Price took it upon himself to incite union men to commit offenses... Following out this scheme Price and four policemen arrested twenty-four union men and charged all but one with the heinous offense of being drunk...(The San Francisco Examiner September 10, 1901:5).

Later that month Lieutenant Price ordered wholesale arrests of union men, without cause, again charging them as drunks. In three days in mid-September, at least 104 union men were reportedly arrested in this way (The San Francisco Examiner September 24, 1901:4).

The Employers’ Association had a problem; there were not enough police available to guard every truck and dray and carry out the Chief’s instructions to drive the union men off the streets. Already by July 31 there were 400 police detailed to ride on and guard trucks all day. This was over two thirds of the total police force and the maximum number the Police Department could spare for such work. Dozens of teams and drivers were ready to go out, but could not due to lack of police protection, adding to the tie-up of the waterfront area (The Examiner August 1, 1901:2). This led to the city authorities, at the behest of the Employers' Association, to adopt the policy of hiring and deputizing large numbers of “Special Policemen,” questionable characters that could then engage in violence under the cloak of authority. There were already 125 “specials” by August 12, when 200 more were sworn in. These paid guards were armed with pistols and clubs (The San Francisco Examiner August 12, 1901:1).

The Police Commission, at the request of the Employers’ Association, eventually appointed 685 special policemen, giving the Employers a greater number of policemen than were on the regular force. Even though some of the appointments were later revoked, the very large number of “specials” was nevertheless remarkable. The Examiner (August 28, 1901: 1) pointed out that the Commission rushed through the appointments without a full inquiry into the character of the applicants. Teamsters’ Union men also noticed “that many of the policemen on duty have been receiving little presents and other favors for their service,” and complained that the policemen should be strictly non-partisan, but clearly were not (The San Francisco Examiner August 2, 1901:2).

Given these facts, it is remarkable that only a few men were killed and several hundred injured during the strike. There could have easily been many more casualties. That there were not is a tribute to the overall restraint shown by the strikers, who were given great provocation. There were many newspaper reports of police and special deputies attacking strikers:

While thus employed Harris ordered Griffith to move on. A fight followed, and Griffith took Harris’ cane from him. Another man took the Special Policeman’s revolver. Feld then arrested Griffith, clubbing him so severely that he was sent to the receiving Hospital... (The San Francisco Examiner August 4, 1901:29).

Two non-union teamsters, who imagined that they were to be attacked by some men who were chatting on the sidewalk at the southwest corner of Sutter street and Grant avenue last night, drew revolvers and fired across the street. The knot of men scattered... Women screamed and dodged into doorways to escape the flying bullets. When the revolvers of the non-union men were empty they scurried away and took refuge in an opium den on Bush street, leaving one wounded man behind them on the sidewalk and another nursing his side, which was grazed by a bullet that went through his coat...The Police Commission at its last meeting gave them permission to carry the revolvers they used last night... (The San Francisco Examiner August 18, 1901:1).

Policeman Orman H. Knight was found guilty of battery yesterday for having clubbed James Madison, a marine engineer, in front of the Oceanic dock about a week ago (The San Francisco Examiner August 22, 1901:4).

Peter Callahan, a marine fireman, living at 542 Harrison street, who was doing duty as a picket in the ranks of the strikers, was shot and perhaps fatally wounded early last night by Edward Furey, a special policeman, who was recently appointed by Chief of Police Sullivan, given a star and permitted to carry a revolver. Witnesses of the shooting state that Furey was the aggressor... (The San Francisco Examiner August 22, 1901:2).

Otto C. Colby, a recent arrival in the city, carrying a club and revolver provided by the Curtin Detective Agency, used that club yesterday on John Lavin, a marine fireman, beating him within an inch of his life. The assault occurred at the coal bunkers of the Pacific Coast Company on Beale street, where Colby claimed to be on duty as a special policeman, although he was without a star, had never been sworn in and could show no warrant of authority. Lavin received two long and deep cuts on his scalp. His right ear was almost torn off and behind it was another cut on his scalp. On his right arm were many bruises inflicted with the club (The San Francisco Examiner August 24, 1901:2).

C. Falkner, one of Chief Sullivan’s recent appointees as a special policeman, fired five shots last night into a crowd of young men at Turk and Jones streets... Falkner is one of John Curtin’s force. For several days he has been riding around on a truck with a non-union teamster. He was walking up Turk street... when...one of the men in a crowd standing there made some remark. Falkner resented it, and some blows were exchanged. The special then ran into the middle of the street and drew his revolver...fired five times at the young men ... (The San Francisco Examiner August 28, 1901:5).

High Morale, Militant Struggle: Mass Meetings, Demonstrations and Labor Solidarity

To keep morale high during what was a long and difficult strike, a number of mass meetings and at least two major organized union demonstrations took place. The first demonstration on August 24, was a “parade for unionism.” About 9,000 people took part, with the biggest contingents coming from the Longshoremen, Teamsters, Sailors, Machinists and associated trades, the Packers, Porters and Warehousemen, and the Marine Firemen (The San Francisco Examiner August 25, 1901:17).

A much bigger event took place on Labor Day, September 2, 1901. Under headings like “Army of Labor Marches Twenty Thousand Strong” and “Workers Furnish An Object Lesson”, The Examiner described what it called “...the largest outpouring in the annals of San Francisco. It was more than a mere display bent on holiday observance. The men in the ranks were there for a loftier purpose...” (The San Francisco Examiner September 3, 1901:1).

The Coast Seamen’s Journal (September 4, 1901:7), described the parade in detail: “A close estimate places the numbers in the parade at 20,601. In addition there were one hundred and fifty carriages and several wagonettes occupied by the women unionists, eight floats and a dozen bands...“

The approximately 20,000 marchers were divided into five divisions, the largest contingents being 3,000 Longshoremen, 1,200 Sailors, 1,100 Boilermakers and Boilermakers’ helpers, 1,000 Teamsters, 1,000 Machinists and 1,000 Packers, Porters and Warehousemen. The fifth division was made up of the City Front Federation:

...it was so large that it had to be divided into three sections. Marshall Ed Anderson wore a uniform and the longshoremen of four unions followed him, marching eight abreast and in close order...The warehousemen from Crockett and Port Costa came down to join in this part of the display, and there was also a representative body of machinists from Vallejo. “In Union There is Strength” and “United We Stand” were conspicuous mottoes.

The shipjoiners, calkers, riggers and hoisting engineers were followed by the attractive float of the marine painters, a sloop decorated in red, white and blue and filled with merry children. The piledrivers and trestle builders took out a donkey engine and piledriver. The engine tooted clamorously and the piledriver was worked with vigor...

The Brotherhood of Teamsters and the sand teamsters headed the second section of the Fifth Division and were cheered everywhere. The brotherhood showed a new silk flag and a banner announcing the union’s organization on August 18, 1900...

Then, making up the last section of the Fifth Division and bringing the procession to a close, came the Marine Firemen, the Sailors of the Seamen’s Union, many of whom were in their natty uniforms of white and blue, and the marine cooks and stewards. The marching of this section was noticeably fine... (The San Francisco Examiner September 3, 1901:2).

At the rally after the march several speakers, including strike leader Andrew Furuseth, addressed the workers. Furuseth said the workers were winning the strike, that the employers had tried starvation, scabs and dividing the labor force, but had failed to break the strike. Their final tactic, he correctly predicted, would be to try to bring in soldiers and cause rioting. He urged the assembled to defeat this tactic by turning: “...yourselves into martyrs. Suffer any indignity. But don’t let them to draw you into any violence. I was told three months ago that we would be forced into a strike, incited to violence and then soldiers would be called in. This was to break the organization of labor. If you don’t know what to do, find out what your enemies want you to do and then -- don’t do it...” (The San Francisco Examiner September 3, 1901:4).

Another way to unite and inspire the people was through mass rallies. Several were held, but probably the most important was held on September 21, at the Metropolitan Temple because it highlighted the powerful oration of Father Peter C. Yorke, a local Catholic priest. Father Yorke had gathered a following and became a key player in the strike because of his ability to speak clearly about the key issues in the struggle. Yorke had been reluctant to get involved, but he was at last convinced. He said:

... we were face to face with a most serious condition of affairs, that the labor unions of California were threatened with extinction and that a cavalcade…on horseback was formed for the charge to ride roughshod over the wage-earners of this city and the State. Being so convinced, my duty was plain, and all my powers were at the disposition of the men who were battling so nobly for the elementary rights of American citizenship. It will be seen, therefore, that I did not push myself into this controversy. I held back as long as I could... But when I was asked by those who had a right to ask me, whose need gave them a claim upon me, from whose ranks I am sprung, who are bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh, mine own people, who am I that I should refuse them what is theirs? (The San Francisco Examiner September 25, 1901:4).

Speaking to the workers at an evening meeting, Yorke argued that as a Catholic priest he was:

…Sent out from that little home in Nazareth where Jesus and Joseph worked for their daily bread. And if being such if I were not found on the side of the poor, when I go back to my Master he would say to me, “I never knew you.” I owe no apology to anybody to speak in behalf of labor, but I should owe an apology to the past, to the great men of the past, and to those who founded my church, if I were to be found in any place except the place I am to-night (The San Francisco Examiner September 22, 1901:19).

Yorke then went on to discuss his view of the real meaning of the current struggle for freedom and the duty of working people:

I believe that you are engaged in a struggle that goes down to the very foundation of things...You are fighting for a principle, and it is principle that makes life worth living, ...It is principle that gives dignity to everything that men do...Between the people who were locked out and the Employers’ Association, there was a difference of principle and that difference of principle cannot be compromised...

The principle of the Employers’ Association...practically all the capital in the city of San Francisco engaged in wholesale and manufacturing business, and I am afraid, the banks also -- is that unionism must be destroyed...there must be no compromise with unionism; unionism must be torn up by the roots, cut up and thrown in the fire...That is their principle.

I believe that the principle of the workingmen, not the teamsters alone, not of the City Front Federation, but of all the other unions of workingmen in the city is, that unionism must be preserved...

... All the rich men and hangers-on of the rich men of the city got together -- against what? Against the teamsters? Not much. Against the longshoremen? By no means. Against every man and every women who is earning wages in the city of San Francisco, in the State of California...

If the rich men are all sticking together...what is the duty of the people who earn wages? Is it not their duty to stick together as close, if not closer, than the rich men? The poor have nobody to defend them but themselves, let me tell you again and again. You have nobody but yourselves... The rich men unite against you, and it is necessary for them to be united, it is ten thousand times more necessary for every man and woman of you to stand shoulder to shoulder, and to be knit together with bands of steel...

So I say to you that the man who tries to put division between union men and union men is an emissary of the devil... if you are a man who is earning wages, a union man committed to union principles, you are a brother to every other union man... (The San Francisco Examiner September 22, 1901:20).

Father Yorke subsequently wrote several articles for The Examiner, and two of these are worth briefly quoting as well. One dealt with the question of violence and non-violence: