California Labor School

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

An art show by students from the California Labor School in Union Square c. 1954.

Photo: Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

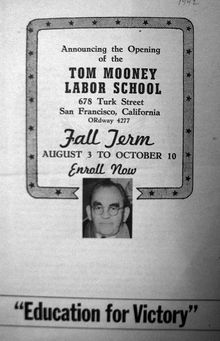

Original catalog pamphlet for Tom Mooney Labor School

Image: Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

The California Labor School was originally founded at the edge of the Civic Center, at 678 Turk Street (at Van Ness), as the Tom Mooney Labor School in 1942. After a modest beginning, it grew quickly. In 1944, the school changed its name to the California Labor School and moved to a five-story building in downtown SF, where it enjoyed the support of more than 100 trade unions and many leading figures in the academic, industrial, banking, art and professional worlds. Five thousand students attended classes that year. After WWII ended, thousands of GIs returned to the US and many sought to use the GI Bill to go to school. The California Labor School was an accredited institution and GIs were able to get support to attend classes. Additionally, the California Labor School served as one of many local hosts for visiting dignitaries during the founding convention of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945.

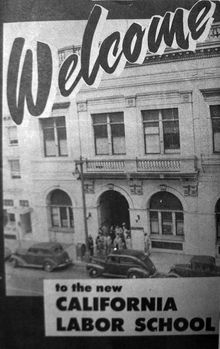

Catalog for the then-new California Labor School at 240 Golden Gate Ave., 1948

Image: Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

During 1946 the school continued to build on its successes, and co-sponsored an institute on labor education with the University of California at Berkeley, and expanded its campuses to Oakland, Berkeley, and Los Angeles while holding classes up and down the state. In 1947 it bought 240 Golden Gate in the Tenderloin and moved its operations there. By this time the California Labor School had come under repeated attacks by the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the head of the California Federation of Labor, among others, for being “communist dominated.” To calm the public furor the California Labor School withdrew from the GI Bill program, forgoing federal tuition monies. But the anti-communist hysteria only grew more frenzied in the years that followed. In the month after the move back to the Tenderloin, Walter S. Steele of the American Coalition of Patriotic Civic and Fraternal Societies, testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that Dr. Frank Oppenheimer taught “atomic energy” at the “San Francisco party school,” by which he meant the California Labor School.

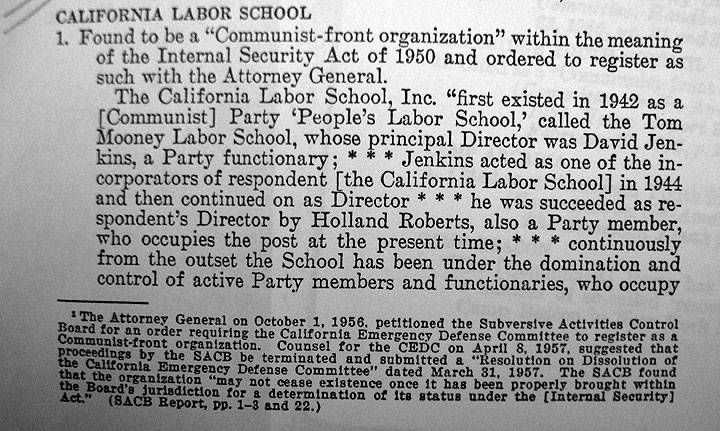

In 1948 the IRS removed the tax-exempt status of the school, while the California Attorney General listed the school as a “subversive” institution. HUAC continued to publicly condemn the California Labor School and other “communist schools” as a “deadly danger.” The persecution continued until in 1950 the federal Congress passes the Internal Security (“McCarran”) Act over President Harry Truman’s veto, after Truman said in his veto message that passing the Act would put the government “in the thought control business.”

Section in the HUAC publication on subversive organizations naming the California Labor School.

Image: Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

Dave Jenkins was the director of the California Labor School from 1942-1949, during which time he was also a member of the Communist Party until he quit in 1956. In his oral history “The Union Movement, the California Labor School, and San Francisco Politics, 1926-1988,” interviews conducted by Lisa Rubens in 1987 and 1988 (Regional Oral History Office, the Bancroft Library), he describes some of the peculiar internal politics that erupted during his tenure:

There was a demand for total participation in the leadership of the [California Labor] school from janitor to money-raiser. It was kind of a democratic anarchy that was leading this really because none of them were willing to go out and raise money. None of them were willing to work with the labor movement which fell almost exclusively to me.

By 1948, I was tired. The [Communist] Party at that time then started to challenge the question of our most popular classes which were in the field of psychology and psychoanalysis. We had probably the most popular lecture series in the city. Sometimes there was standing room only literally; we used psychiatrists and mental health workers in a variety of fields… The Party in effect asked us to stop the classes when they themselves passed a ruling that anybody that was a psychiatrist or was in therapy had to drop out of the Party. The claim was that these people were no longer trustworthy, which was stupid. As a matter of fact, during this whole period of increased red-baiting, the ones who had been the most stalwart and the most to the left were the psychoanalysts and the Psychoanalytic League. There was a certain rationale that people were telling their all to the psychologists who if coerced by the FBI could be dangerous. The whole handling of these matters was poor.

By 1948 the progressive and Left unions were expelled from the CIO, the veterans’ program at the school started to be attacked; the Tenney Committee was starting to subpoena me and others. Bridges was started to get re-indicted. All this meant the end of the school really. I often speculated that if we had taken a position to the right of the [Communist] Party, that the school could have flourished and continued to be a major institution. But I think I am probably wrong because the Party was so much a part of the school that it would have been torn apart if I had led a direction which rejected the Party Line of the time, rejecting getting involved in the politics of Henry Wallace’s campaign, or the Marshall Plan, or the CIO unions' expulsion.

It was my decision to leave the school; nobody removed me. I was given a big dinner and a gold watch and stayed on at the school a little bit, but Holland Roberts effectively took over. While I had enormous affection and respect for Roberts, he was totally intimidated by the Party leadership. We would have independent meetings at the school and say we were going to fight on the classes in therapy and psychoanalysis or agree we would take a position on something else. But once the Party objected, he would cave in.

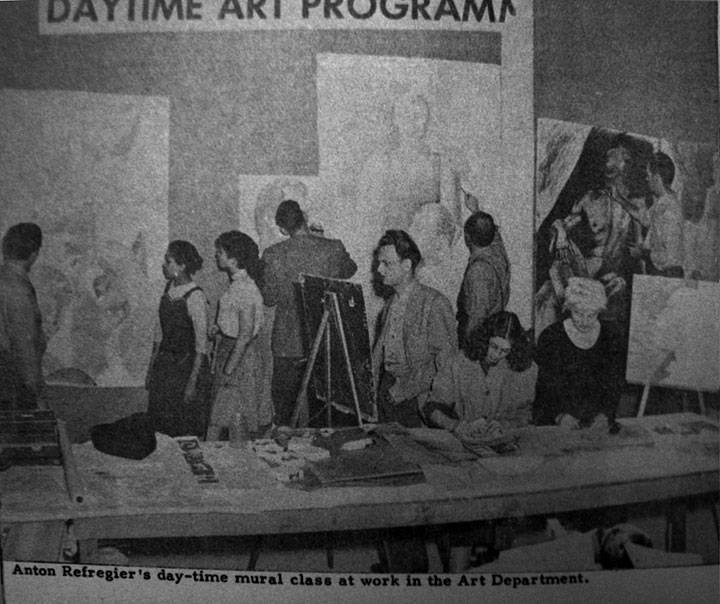

Anton Refregier, muralist responsible for the controversial Rincon Annex murals, taught a painting class at the California Labor School.

Image: Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

Under relentless pressure from federal and state anti-communist politicians, enrollment and finances collapsed. In 1951 the School moved to smaller quarters on Divisadero. Government efforts to destroy the school continued unabated, and by 1957, the California Labor School closed its doors for good. After the IRS seized their desks, books, and papers, the School’s final act was to hold a big May Day party in 1957.

Joint Action Committee of California Labor School Peoples' Songs Branch giving an agitational performance on the waterfront, c. 1948.

Photo: CLS collection, Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

In the mural room in the basement of the California Labor School at 240 Golden Gate.

Photo: CLS collection, Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

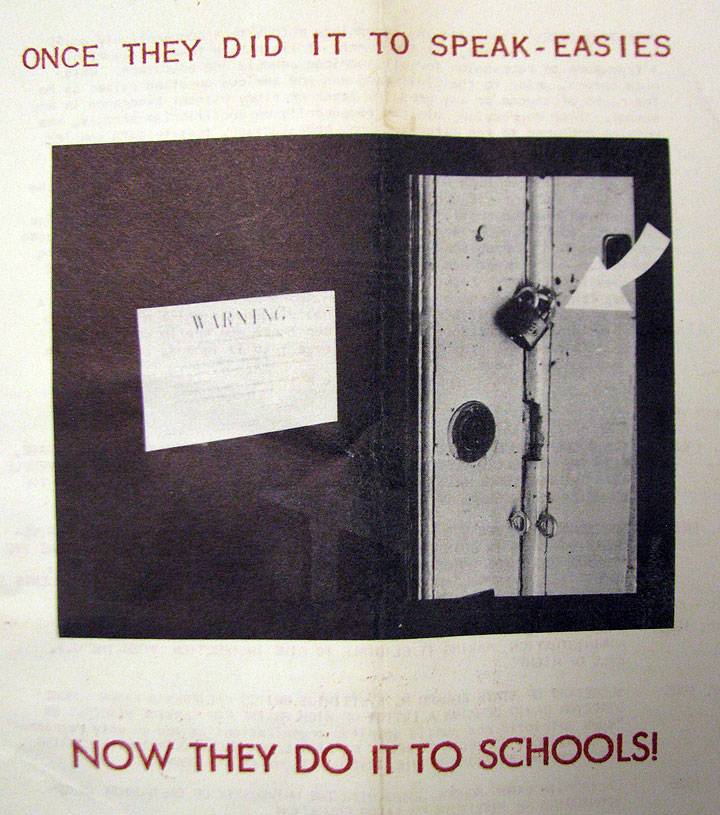

Later, a pamphlet was issued describing the step-by-step campaign of harassment and persecution that finally closed the school under the title, “Once They Did it to Speak-Easies, Now They Do it to Schools!”

Cover of the pamphlet.

Photo: CLS collection, Labor Archives at San Francisco State University

Their own closing comments were these:

During the eleven years of witch-hunting endured by CLS, it continued unremitting activity along various cultural and educational lines. In addition to classes in the social sciences, literature, graphic arts, theatre, writing, and the dance, lecturers and guest artists at a steady stream of important affairs included Frank Lloyd Wright, Peter Seeger, Jenny Wells Vincent, Anton Refregier, Dr. Howard Selsam, Paul Robeson, Vincente Lombardo Toledano, Fred Langhorst, Freda Koblick, Paul Radin, Julius Stern, Anthony Boucher, Emmy Lou Packard, Antonio Sotomayor, Dr. Herbert Aptheker, Pablo O’Higgins, Dr Philip Foner, Dr. Joseph Wortis, Maud Russell, Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, John Howard Lawson, Lloyd Brown, Adeline Kent, Keith Monroe, Lincoln Fairley, Byron Randall, Doxey Wilkerson, Cedric Belfrage, Mime Kagan, Robert McChesney, Mara Alexander, Joseph Starobin and Dr. Joseph Furst.

The Labor Theatre produced dramatic readings and smash hits: “Stevedore” and “Bury the Dead”; organized under the school’s direction, the New Group Theatre produced “The Little Foxes,” “Golden Boy”, and “Othello.” The Labor School Chorus was a famous institution. Its presentations ran a wide range from the satiric comedy of “Trial by Jury” to the majestic simplicity of “Yellow River Cantata” and “Song of the Forest.”

Leading artists contributed to exhibits and taught in the Artists’ Workshop. There were Writers’ Workshops, first under Alexander Saxton and later under Mike Gold. There was a literary magazine. Reports were made by delegates to cultural, peace and other conferences of an international character abroad. There were topical revues and variety shows, such as “Ring That Bell” and “What’s Left;” folk music forums and hootenannys, dinner meetings and songs of Negro liberation, panel discussions, program of modern music, and showings of unusual motion pictures—some foreign and some revivals of the best from Hollywood. And there was never a February but what the school didn't celebrate Negro History Week.

It was a busy and fruitful place.

Before the doors were forever closed however, the artists and some of the CLS faculty moved the litho presses and other equipment to a studio on Francisco Street in North Beach and Graphic Arts Workshop was formed.