Debunking ’60s Myths and Catchphrases

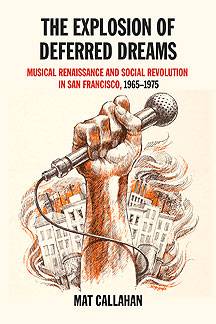

Historical Essay

by Mat Callahan

This is Appendix 1 in Callahan’s book The Explosion of Deferred Dreams: Musical Renaissance and Social Revolution in San Francisco, 1965-1975, (PM Press, Oakland: 2017) published here with permission.

Crossing street at Masonic and Haight, 1967.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P15566)

The system, the movement, consciousness and liberation

The system not only referred to capitalism or to economics. The system represented the constellation of forces that dominated and controlled all aspects of social life from sexual mores to the oppression of black people, from the exploitation of labor to the suppression of student protest. Above all, it was not confined to the United States but included the Soviet Union as well. The system was everything that kept people down and it had to be overthrown or radically transformed; it could not be reformed and preserved. Furthermore, it was doomed.

The movement was a direct outgrowth of the civil rights and anti-war movements that gave it birth but it was also the grandchild of the labor movement and the peace movement of an earlier generation. It was an all-encompassing term that invited people in without requiring membership cards or dues. Thus, by 1967 a supporter of the farmworkers and an organizer of draft resistance or a GI coffeehouse would consider themselves part of the movement. For the millions swept up in this great undertaking, the system was the enemy; the war in Vietnam, the oppression of blacks and Chicanos and the alienation of youth were just the most grievous signs of its depraved nature. By 1970, women’s liberation, environmentalism and the struggle for gay rights grew out of and in turn radically transformed the movement itself.

Consciousness expansion came into wide use in the years between 1965 and 1970 referring to everything from LSD to Nietzsche to Buddha to Mao. Women’s liberation inspired the even more widespread use of the term “consciousness raising.” In any case, this was no ivory tower, academic debate. This was a serious pursuit by large numbers of ordinary people coming to grips with philosophical, political and spiritual questions that inevitably erupt when people aspire to more than merely improving their lot within an oppressive social order. And people did, generally, aspire to more. The idea of a revolution of some kind ushering in a truly different world had fired the imaginations of many who thought at the time that their victory was both assured and imminent. That they (we) were wrong about this does not alter the point.

Liberation was originally inspired by the independence movements that swept Africa and Asia in the early Sixties. The right of nations to self-determination was part of the UN Charter signed in 1948 and was given significance by the collapse of Europe’s colonial empires in the face of popular revolt following WWII. But the greatest spur to widespread use of the word came from the National Liberation Front in Vietnam. As resistance to the war merged with the struggle of black people for civil rights, both movements moved from focusing on specific targets to a wholesale assault on the system in the interest of people’s liberation everywhere. Thus the civil rights movement gave way to the struggle for black liberation.

Inventory of Falsehoods

First, there was no “San Francisco Sound.” Even though Ralph Gleason’s enthusiastic boosterism led him to use the term, he would be the first to admit that it has been construed in a manner other than he intended. Declarations of a“sound” of a city are often of dubious musical or historical value. In the case of Detroit, Memphis, Chicago or New Orleans there might be some merit in using the term, since a cohesive musical style and tradition did develop (albeit for different reasons in each case). In the case of Detroit, a small group of inspired musicians, calling themselves “The Funk Brothers,” became broadly influential through the intrinsic quality of what they created in combination with the popular success of Berry Gordy’s marketing of the “Motown Sound.” In the case of New Orleans, this was a more generic process spanning decades in which a combination of African and European influences produced a distinctive local music.

But San Francisco never had any single, defining musical style, certainly not one that originated there. In fact, it was the absence of any one sound that opened a space for the diversity that came to be identified with San Francisco. Such diversity was only possible because of what many musicians have emphasized since: the audience was decisive. This public welcomed anything it perceived as authentic, innovative, wild and free regardless of its stylistic particularity. What had hitherto been sharp, apparently irreconcilable, divisions between folk, jazz, rhythm and blues and rock music underwent an alchemical transformation. Everything is permitted where God is dead, and if rock ‘n’ roll was anything, it was the slayer of gods. Present, even, were the works of contemporary composers such as Moondog (Louis Hardin), Morton Subotnick and Terry Riley. What happened as a result was more than the creation of a large body of work. Instead of one sound or genre, music as such was elevated to the position formerly held by poetry as the queen of all the arts. To paraphrase Shelley, music became the unacknowledged legislator of the world.

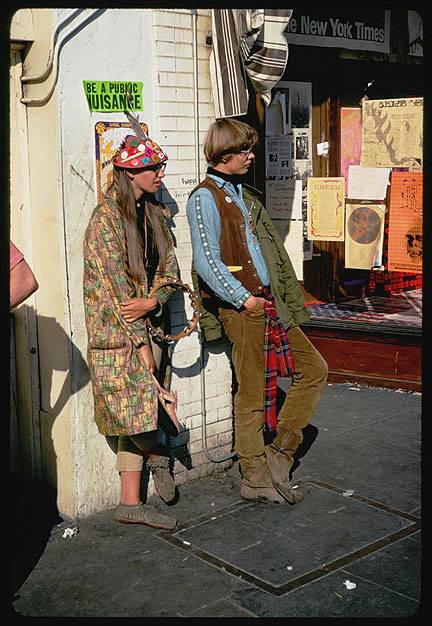

Hippies on Haight Street, October 26, 1967.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P15596)

Second, there was no “Summer of Love.”(1) This was a media creation that passed into popular usage the way Tampax became the generic name for a sanitary napkin. It was accomplished by the same means. Journalists and publicity agents (and is there really a difference?) repeated this phrase so often that it became a common referent; it was a short, easy way to identify a time and place without doing the hard work of chronicling what actually transpired, thereby preventing its lessons from being learned. A large migration of young, mainly white, high school and college age people did came to the Bay Area in 1967 attracted by its growing reputation; along with the tour busses, many subsequently found themselves wandering up and down Haight Street.

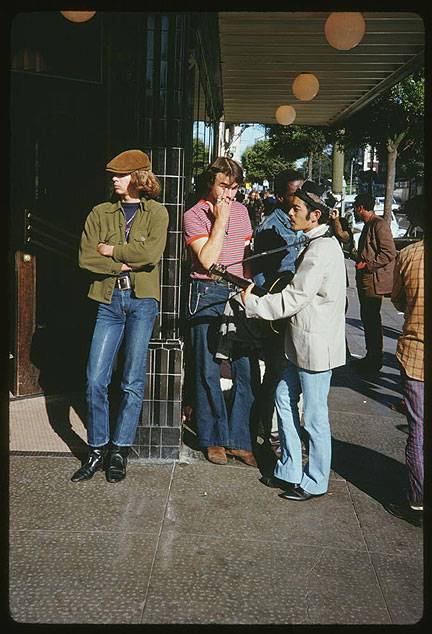

1967, hanging out at Haight and Masonic.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P15560)

The Diggers, The Family Dog, The Oracle newspaper and the Straight Theater did use the phrase in a press release of April 5, 1967 to announce a series of celebratory events and community activities including sweeping the streets. But love had a lot less to do with this than is commonly believed, as the press release and coinage of the phrase were an attempt to give some direction to what exploded in January of that year at the Human Be-in when at least 20,000 people had attended a “Gathering of the Tribes” in Golden Gate Park. The local organizations had to deal with the response of the authorities, including repeated instances of police violence. In 1967 alone, the police carried out several massive sweeps down Haight Street, beating and arresting everyone in sight, sending plenty to the hospital and charging anyone they chose with assaulting a police officer.(2) The stakes were raised higher since plans were afoot for a giant festival (the Monterey Pop Festival) that, along with the song “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair),” released in May 1967, sought to capitalize on a growing anti-authoritarian sentiment. The festival itself generated bitter controversy that was nonetheless overshadowed by the music performed there. Indeed, in musical terms, Monterey Pop was a brilliant representation of what San Francisco’s openness and creativity had inspired. But the music industry was moving in, forming (along with police repression) the second jaw of a steel trap.

To put this in its broader context, it is doubtful that these events would have occurred or caused more than a ripple, were it not for the ferment in society arising from the civil rights and anti-war movements. The Human Be-in was a conscious attempt by its organizers to unite the overtly political movement with the nascent, and as yet unnamed, counterculture (often referred to at the time as the “socially hip movement” or “hip community.”) “Summer of Love” and its abiding image of a pilgrimage to a psychedelic Lourdes furthermore obscures the intensely local phenomenon of San Francisco in the Sixties, its driving personalities and participants coming from within the Bay Area as much as from without. Most importantly, the “Summer of Love” designation cannot be applied to the extraordinary growth in size and influence of the Black Panther Party, founded across the Bay in Oakland in 1966. The connection, for example, between the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Diggers and the Panthers was not simply temporal coincidence. The people involved met, exchanged views, mutually influencing and supporting each other. Such activity took place in Oakland, the Mission, Fillmore and Tenderloin neighborhoods, not only in the Haight Ashbury.

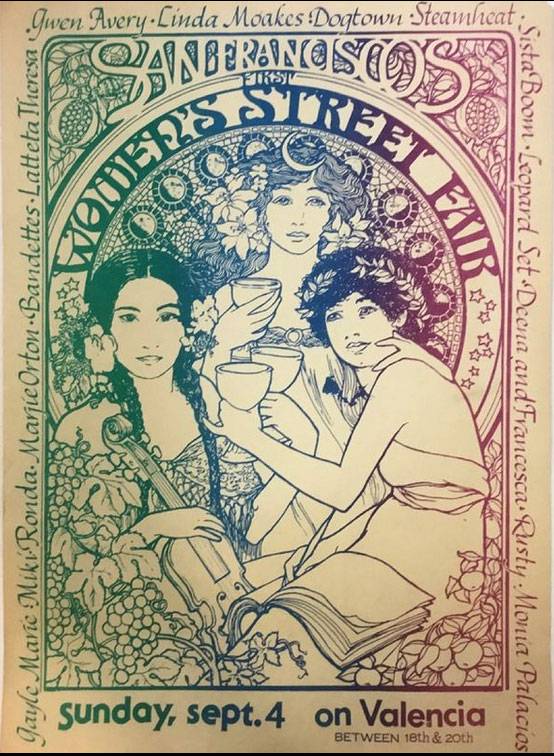

First Women's Street Fair, Sept. 4, 1966 on Valencia Street in the Mission, at the dawn of its development into a Lesbian corridor.

Third, there was no “hippie movement” or “hippie revolution.”The term “hippie” was considered a pejorative and was not used by anyone considering themselves“hip.” The origin of the term is instructive, however, since it illustrates how naming and authority are mutually dependent.

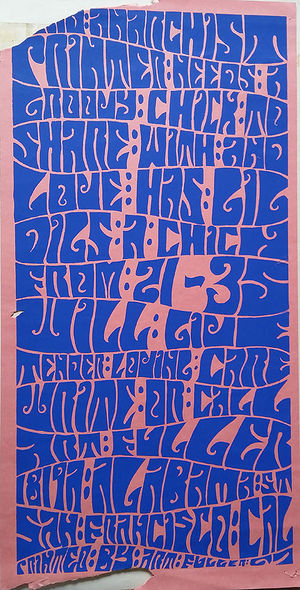

Clever classified ad poster around the Haight Ashbury in 1967

courtesy Eric Noble

A coffeehouse called the Blue Unicorn opened its doors on the north side of San Francisco’s Panhandle in 1963. Its claim to fame was the cheapest food and coffee in town, so it naturally appealed to those with little money such as the artists and students, house painters and cab drivers who frequented the place. The Blue Unicorn’s reputation steadily grew until it came to the attention of one intrepid reporter for the San Francisco Examiner, Michael Fallon, who announced its existence to the world, September 6, 1965, in an article entitled, “New Haven For Beatniks.” Perhaps the article was only coincidentally published at the height of the battle raging over a freeway to be built parallel to the Blue Unicorn through the Panhandle. This battle became known as the Freeway Revolt. The San Francisco Examiner, owned by the family of William Randolph Hearst, supported the building of the freeway. Could this have been the ulterior motive for drawing attention to an otherwise innocuous business establishment?

Among the ideas fueled by caffeine and conversation was “The Unicorn Philosophy,” courtesy of owner Bob Stubbs. An excerpt quoted by Charles Perry in The Haight Ashbury, reads as follows: “It is nothing new. We have a private revolution going on. A revolution of individuality and diversity that can only be private. Upon becoming a group movement, such a revolution ends up with imitators rather than participants...It is essentially a striving for realization of one’s relationship to life and other people.”(3) “Nothing new?” “Revolution”? “Private”? That wouldn’t by any chance be an effort to fend off the authorities who unsurprisingly descended on the Blue Unicorn shortly after Fallon’s piece was published?

It is certainly a favorite tactic of authorities to harass or shut down anything even mildly subversive particularly if it just happens to be in the path of their bulldozers. So San Francisco’s Public Health Department cited the Blue Unicorn, forcing it to close. Is it just coincidence that there had been weekly meetings there for at least a year sponsored by LEMAR (legalization of marijuana) and the Sexual Freedom League? After a month, the Unicorn reopened and managed to stay afloat for some time. But by then, the vultures had smelled blood. Something was happening and Mr. Jones didn’t know what it was. So the best thing to do was to give it a derisive name, “hippie,” and spread that name far and wide.

What “hippie” sought to ridicule was real enough, however. Young people started growing their hair long, wearing colorful clothing, listening to rock music, smoking marijuana, dropping acid and began calling themselves “heads” or “freaks.” They also began calling each other brothers and sisters. “Hippie” was always viewed as the straight world’s appellation of scorn. Indeed, “hippie” was usually accompanied by, “get a haircut,” or “take a bath.” What often followed was harassment and physical abuse by the police.

In any case, the real news was not the Blue Unicorn. It was the launching of the Haight Ashbury Neighborhood Council and its successful mobilization to oppose the freeway. What might have become of San Francisco in general and the Haight in particular, had that freeway been built? Contrary to manufactured myth, the Haight Ashbury was by 1967 a battleground, the site of low intensity civil war. Many if not most people spoke in terms of the movement in the broadest sense (counterculture had not been coined yet), meaning everything from opposing the war in Vietnam to the struggle for civil rights or, for that matter, the farmworkers. The Diggers’ “Death of Hippie/Birth of Free” march down Haight Street in 1967 was one of many events drawing the line between the system’s machinations and the people’s aspirations. Digger interventions played a decisive role in articulating explicitly anti-capitalist views shared by a large and growing number of young people. Their Free Store, Free Frames of Reference, free food and regular distribution of mimeographed messages were rallying points aimed at turning a spontaneous outpouring of rebelliousness into a conscious attempt to change the world.

Fourth, “peace and love” did not characterize daily activity nor did it reflect prevailing Sixties attitudes on Haight Street, or anywhere else for that matter. Certainly, many championed the ideals of peace and love, but at the time these were highly charged political terms, not abstractions floating in the ether. Peace meant opposition to the war in Vietnam. Love meant opposition to the brutality of the police in particular and authority in general. Macho images such as the jock, the drill sergeant or the cowboy were love’s targets, since it embarrassed them profoundly.

Furthermore, violence and brutality of a political nature had by 1965 become commonplace in American life. Not only were Black people being attacked by southern racists and cops everywhere,but so were young whites protesting against the war. As mentioned earlier, Haight Street itself was attacked on several occasions by the San Francisco Police. Besides, this was the era of the occupation and of demonstrations to free political figures, such as Huey Newton, imprisoned by the System.

Fifth, the misuse and abuse of the term “counterculture.” Theodore Rosczak’s book is important to this day, since even if one disagrees with his conclusions, one has to take into account the broad influence of the work and the subject matter chosen by its author. For example, the social critics that focus his discussion (including Herbert Marcuse, Paul Goodman, Norman Brown and Allen Ginsberg) give some indication of how widely read such writers were. Leveling a sustained attack on the Technocracy is also instructive not only in terms of the arguments (many remain valid to this day) but in terms of how prevalent such views were at the time. The way in which the term “counterculture” became pervasive is another matter. I question it on two grounds: 1. All oppositional movements develop “cultural” expression that reinforces solidarity while critiquing the dominant or oppressive culture. Certainly, black people developed a culture counter to the dominant one and Rosczak goes to great pains to point out that it would take another book to adequately address what was happening with black youth, and, 2. Its attempt to circumvent class, ethnic or gender identifiers is useful but problematic. It is certainly true that young people of all ethnicities, classes and genders (including gays and lesbians) were among those who fit into the category “counterculture.” But, as subsequent events demonstrated, it was a designation that was easily manipulated for contradictory purposes. Indeed, it provided the very tools by which cooptation and commodification was achieved. Even at the time, the counterculture was frequently pitted against the movement both as a description of constituencies and as social vision. This was certainly not what Rosczak intended, as is clear if one reads his book. From the outset, Rosczak identifies the counterculture as a resistance movement, in some ways even more revolutionary than its conventionally political counterpart. He explicitly discredits attempts to categorically separate the two in any case. Rosczak sought to provide a means by which serious discussion of a social phenomenon could be joined without falling into the categories of doctrinaire Marxism or of classic liberalism. Few from the Old Left or Johnson’s Great Society had anticipated let alone adequately responded to the demands of youth as a social force. Citing Marcuse, in particular, speaks to both Marcuse’s exceptional influence as well as the content of that influence, namely, the necessity of revolutionary social transformation and its re-envisioning by the New Left.

Sixth— the claim was wrong that the whole thing was white and middle class, for all intents and purposes conforming to Ronald Reagan’s portrayal. This is perhaps the most common of all assumptions about the Sixties today,but it is false on several counts. From the outset, people from all social classes, including the children of wealth and the children of workers, were drawn to the movement. Furthermore, countercultural or movement influence spread simultaneously with resistance to the draft and to the war in Vietnam. Soldiers and draft resisters were drawn into “countercultural” activities in increasing numbers, identifying with the music, the attitudes and the politics expressed. This ultimately amounted to millions of people, most of whom were not from well-off backgrounds and many who were black, Latino, Asian or Native American. It was not long, in fact, before young workers of all nationalities were adopting the ways and means associated with their generation rejecting to one extent or another the modes and manners of their forbears, particularly those of organized labor. This applies to the composition of the milieu, but there are two other problems with the “white, middles class” characterization.

Race was the social fault line cutting across and to a large extent determining all others in the United States. The ghettoes (including San Francisco’s Hunter’s Point, which exploded in 1966) were in flames. The mood among black people generally was increasingly militant. Nowhere was this more clearly demonstrated than at Polytechnic High School on the edge of the Haight Ashbury district itself. The school was predominantly black and there was an uneasy but thought-provoking relationship between these young people and the burgeoning street scene through which they walked every day to and from school. This resulted in innumerable petty confrontations, some violent, some merely verbal taunts, but there was no way “hippies” on Haight Street could ignore or be ambivalent towards race. Nor, for that matter, could young black people fail to be influenced by what was obviously exciting and was meeting with extreme repression at the hands of their own enemies, the cops.(4)

Finally, the whole concept of “middle class” has to be critically evaluated. At best, middle class is a rough description of income, occupation and perhaps educational level. But that has little value in determining the participants in the movements of the Sixties, let alone their motivations. Above all “middle class” is a political designation invented to combat the Marxian concept of the proletariat or working class whose historic mission was to eliminate classes altogether.

Originally, the term was used in Europe to designate the bourgeoisie as between the aristocracy and the laboring classes on the other. Following WWII, it became the crucial component of a social model with which the rulers of the United States hoped to defend their power against revolution. In any case, “middle class” was a term of derision, not of aspiration, among drop-outs, freaks and radicals.

Seventh— the mountain of mystification surrounding drugs. LSD and a group of plants with psychotropic properties were used because they produced experiences akin to revelation as recorded by mystics and religious seekers. At the very least, these drugs made users contemplate perception, to think about thinking, that most philosophical of preoccupations. Marijuana is in a special category connected to these hallucinogens, but also independent from them. Its lineage was different, as it was popularized by black jazz musicians and the hipness associated with them. Together, marijuana and the psychotropics have to be distinguished from all other drugs including speed, heroin, cocaine, barbiturates, alcohol, caffeine and nicotine that were in use before and since the Sixties for other reasons, reflecting no change whatsoever in the status quo.

The most damning indictment of the “Summer of Love” nonsense is that by 1967, LSD and pot were being systematically replaced by speed and junk. Anyone who was there at the time remembers the case of Superspade, a black pot dealer, whose murder and that of another dealer that very summer attracted nationwide attention. A Time magazine article appearing on August 18th, 1967 reported: “Says Dr. David E. Smith, founder of a Haight-Ashbury medical clinic that ministers to bad-tripping hippies: ‘Amphetamines are the biggest drug problem now in the Haight.’”(5) The Time article concluded with this retrospectively hilarious quotation, “In an effort to restore peace and quiet, if not sanity, a hippie house organ called The Oracle editorialized: ‘Do not buy or sell dope any more. Let’s detach ourselves from material value. Plant dope and give away all you can reap. For John Carter and William Edward Superspade Thomas—may their consciousness return to bodies that will not want for anything but the beauty and joy of their part in the great dance.’”(6)

While LSD in particular had important social effects encouraging users to reexamine their most cherished beliefs and practices, leading many to reject the prevailing views of a corrupt, hypocritical, consumerist society, it can nonetheless be flatly stated that drugs were mainly important as agents of social bonding, not for their chemical effects. Indeed, taken as a generic designation, “drugs” can never be separated from other factors, such as therapeutic aids, or in the case of “the pill,” its effect on sexual practices and women’s consciousness. “The pill,” in fact, had the most far-reaching consequences of any drug associated with the Sixties.

Dropping Out

Dropping out, made famous by the slogan, “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out,” had many dimensions from attitude to lifestyle to strategy for social change. However, one key element was the social phenomenon of the teenage runaway. The teenage runaway was furthermore closely associated with the Summer of Love, the Haight Ashbury and the counterculture in general. But what was this phenomenon, in fact, and what gave it significance? “The FBI reports the arrest of over ninety thousand juvenile runaways in 1966; most of those who flee well-off middle-class homes get picked up by the thousands each current year in the big-city bohemias, fending off malnutrition and venereal disease,” wrote Theodore Roszak, quoting sources such as TIME’s September 15, 1967 article on the subject.(7) That this was neither confined to the United States nor directed toward San Francisco alone is confirmed: “The immigration departments of Europe record a constant level over the past few years of something like ten thousand disheveled “flower children” (mostly American, British, German and Scandinavian) migrating to the Near East and India-usually toward Katmandu (where drugs are cheap and legal) and a deal of hard knocks along the way.” Roszak concludes, “Certainly for a youngster of seventeen, clearing out of the comfortable bosom of the middle-class family to become a beggar is a formidable gesture of dissent. One makes light of it at the expense of ignoring a significant measure of our social health.”(8)

The authorities in San Francisco didn’t make light of it. They sounded the alarm. Police Chief Thomas Cahill explicitly warned in 1967 that“law and order will prevail. There will be no sleeping in the park. There are no sanitation facilities and if we let them camp there we would have a tremendous health problem. Hippies are no asset to the community. These people do not have the courage to face the reality of life. They are trying to escape. Nobody should let their young children take part in this hippy thing.”(9) But this was after the fact and to a large extent being orchestrated by the Establishment from whom young people were running away. When the Health Department, for example, was called on to investigate living conditions in the newly notorious Haight Ashbury (no similar investigations were planned for the Black ghettos of the Fillmore district or Hunters Point), they found nothing out of the ordinary. After visiting 1,400 residences they found only sixteen in which people fitting the description of hippies could be cited for violations.(10) Long-time Haight residents were outraged by the Health Department’s actions. Led by the Haight Ashbury Neighborhood Association, fresh from the victorious Freeway Revolt, they denounced the city’s “gratuitous criticism of our community.” They accused officials of “creating an artificial problem” motivated more by “personal and official” prejudice than by legitimate concern. The head of the Health Department, Dr. Ellis D. Sox, had to back off. “The situation is not as bad as we thought,” he said. “There has been a deterioration [of sanitation] in the Haight-Ashbury, but the hippies did not contribute much more to it than other members of the neighborhood.”(11) This was not, Dr. Sox maintained, a deliberate campaign against weirdoes, when everyone knew that was precisely what it was.

Two more points about runaways. First, the numbers have to be put in perspective and qualified by what constitutes a runaway as opposed to an adult participant in the same activities. Secondly, there were always conflicting agendas within the Haight Ashbury and the Bay Area at large particularly as regards the organization and mobilization of these youth. The HIP merchants and the Oracle, for example, were only two of several groups with conflicting agendas contending for the allegiance of the young.

In terms of the numbers, estimates have been proposed suggesting that as few as 50,000 and as many as double that number flooded San Francisco between the summers of 1966 and 1968. Reports claimed that the hippies numbered 300,000 nationwide and that enclaves could be found in many cities across the country. The purpose of these reports, however, was not quantification of a population but the construction of a type that could be marginalized and isolated.

There were at least as many, if not more, young people from local high schools and even junior high schools who participated in the Human Be-in, to use only one noteworthy event as an example. Young people flocked to San Francisco from other parts of the Bay Area, swelling the ranks of gawkers and idlers on Haight Street on a regular basis. Most of these were not runaways, even if they were juveniles.

Actual runaways were by definition a temporary phenomenon, since adulthood would mean they were no longer the responsibility of their parents. More importantly, what brought them together in the Haight Ashbury as opposed to San Diego was more than their status as runaways, which could apply to any minor leaving home against the wishes of their legal guardians. Obviously, a combination of factors including dreams, drugs, the draft, distance from families as well as alluring rumor led them to seek security in numbers or solidarity in tolerance. No doubt the most gullible actually believed the song “San Francisco,” just as some thought the Monkees were a real band playing their instruments. But the phenomenon, such as it was, could no more be attributed to music industry hype than could resistance to the war in Vietnam. Ultimately, the runaway was one manifestation of a much larger and more fluid situation. That it posed a threat to the system is not in doubt, but that it also posed a challenge to revolutionaries also became quickly clear.

Roszak put the question provocatively: “the adolescentization of dissent poses dilemmas as perplexing as the proletarianization of dissent that bedeviled left-wing theorists when it was the working class they had to ally with in their effort to reclaim our culture for the good, the true, and the beautiful. Then it was the horny-handed virtues of the beer hall and the trade union that had to serve as the medium of radical thought. Now it is the youthful exuberance of the rock club, the love-in, the teach-in.”(12)

Notes

1. Even Joel Selvin’s book Summer of Love opens with the sentence: “The Summer of Love never really happened.” Selvin, Joel. Summer of Love (Cooper Square Press 1999) pg: Introduction

2. See: Perry, Charles. The Haight Ashbury A History (Wenner Books New York 2005) pp. 89-90, pg. 123, pp.162-3, pp. 208-9, pp. 273-4 each citation reports a different large-scale incident.

3. bid. pp. 19-20

4. this author attended Polytechnic High School at this time

5. Time Magazine, Friday, Aug. 18, 1967

6. ibid.

7. Roszak, Theodore. The Making of A Counter Culture (Anchor Books 1969) pg. 33

8. ibid. pg. 34

9. cited in: Thompson, Hunter S. The Great Shark Hunt, Gonzo Papers Vol. 1 (Fawcett Library 1979) book contains no page numbers

10. Perry, Charles. The Haight Ashbury A History (Wenner Books 2005) pp.159-160

11. ibid. pg. 160

12. Roszak, Theodore. The Making of A Counter Culture (Anchor Books 1969) pg. 41

This essay is excerpted from Mat Callahan's book The Explosion of Deferred Dreams (PM Press, Oakland CA: 2017) with permission.