Decolonizing UC Berkeley

Historical Essay

by Brandy Olson & Kimmy Pantoja, 2023

| Decolonizing UC Berkeley is a legal studies course seeking to engage undergraduate students in a critical investigation of the origins of the University of California through a settler colonial lens, with the aim of decolonizing the University's narrative history. The ultimate goal of the course is to teach students to look critically at the landscape and to approach the world as a place that holds possibility for change, and equip them to go out and change it. The following is an excerpt of a student project outlining some of the history of dispossession in the creation of the university. |

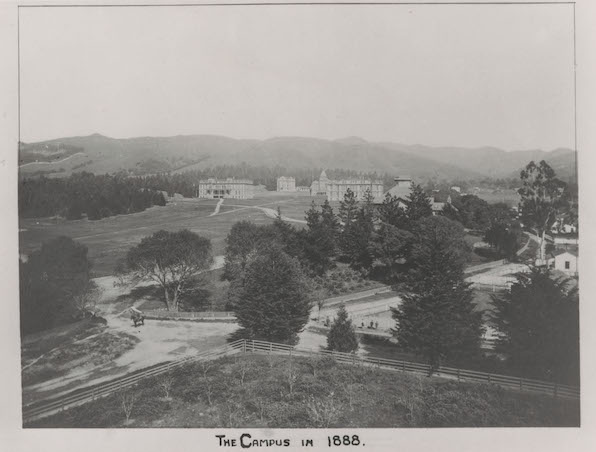

View from roof in vicinity of Dana Street and Allston Way, showing Dana Street entrance to the University of California, Berkeley campus, with North Hall, Mechanical Arts Building and annex, Bacon Art and Library building, South Hall, and dome of Harmon Gymnasium, 1888.

Photo: The Bancroft Library, UARC PIC 3:317

On whose backs was the foundation of the beautiful campus of the University of California, Berkeley laid? The answer begins in 1862 with the Morrill Act, which provided each state with "public" lands to sell in order to raise funds to establish universities, and was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln.

"The land-grant university movement is lauded as the first major federal funding for higher education and for making liberal and practical education accessible to Americans of average means. However, hidden beneath the oft-told land-grant narrative is the land itself: the nearly 11 million acres of land sold through the Morrill Act was expropriated from tribal nations. Due to the California Land Act of 1851, which served to dissolve pre-statehood land claims, the failure of the federal government to ratify 18 treaties made with California Indians, and other systematic acts of genocidal violence and dispossession carried out in the second half of the 19th century, the Morrill Act had particularly dire consequences for California Indians." (1)

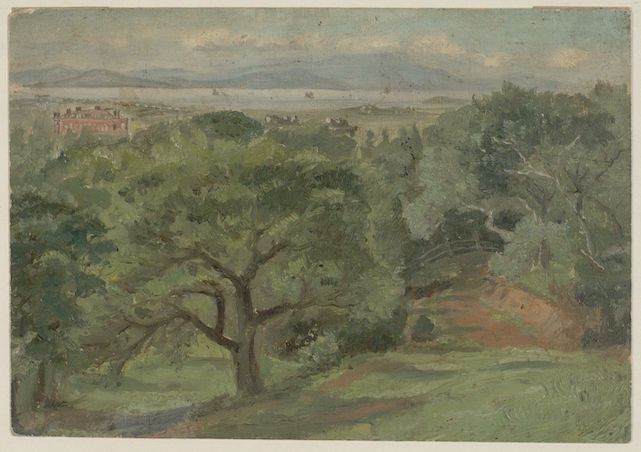

F. Bühler painting of Berkeley overlooking University of California campus, ca. 1881.

Image: The Bancroft Library, BANC PIC 1963.002:1347--A

The Land Grab University movement is just one of the many ways in which California Native Americans have suffered some of the most harm of any tribes in the nation. Besides being subject to Spanish, Russian, and Mexican colonial regimes, California Indians also had to contend with the genocide brought by American prospectors during the gold rush. For tribes native to the San Francisco Bay Area, the land that they had called home for centuries was cleared to make way for the vision of California's richest, most powerful entrepreneurs of the day—a seat of higher learning that would rival the world's greatest institutions, set squarely in the middle of an enchanted piece of land, rich in beauty and rarified air, blessed with a sunset like no other and a breathtaking view of the San Francisco Bay. The Morrill Act not only helped to secure the grounds for the campus, but it also stipulated that "all money made from land sales must be used in perpetuity, meaning those funds still remain on university ledgers to this day," thus continuing to earn interest. (2) UC San Diego Professor and co-founder/co-director of the Indigenous Futures Institute, Theresa Stewart-Ambo, argues that because universities continue to profit from the sale of lands and mineral rights gained through the Morrill Act Land Grabs via the displacement and destruction of Indigenous people and their cultures, Native Californians should be viewed as financial contributors to universities, or stakeholders. (3) This is an example of living, breathing decolonial thinking.

Building upon concepts like this, and utilizing the input, research, activism, respect for cultural practices, native voices, laws, scholarship and energy contributed by a diverse group of scholars and indigenous leaders, The University of California Land Grab Report provides a synthesis of key learnings and recommendations from a two-part forum held in September and October of 2020. While the report generated many specific actions that could be voluntarily adopted by UC Berkeley should the institution decide to put some meaning behind its words, the foundation from which these actions might emerge include two broad points:

The overarching recommendation by the report authors is for the University of California systemwide leadership, along with the leadership of individual campuses and other UC entities (such as the Natural Reserve System and UC Cooperative Extension) to 1) work with California Indian tribes through a transparent, collective process to pursue actions that meet the priorities of Native communities, and 2) dedicate the necessary financial and infrastructural resources to deliver on these actions. (4)

While these appear to be very general suggestions on the surface, they encompass two of the most important elements of meaningful reparations. First, any and all attempts to make amends or implement restorative actions must be done in close collaboration with Native communities. Their voices are essential to this process, their needs must be articulated by the people who experience the harm on a daily basis. Yale Psychologist Dr. Nathaniel Vincent Mohatt defines historical trauma as "a complex and collective trauma experienced over time and across generations by a group of people who share an identity, affiliation, or circumstance." (5) Dr. Mohatt argues that historical trauma consists of three primary elements: "a 'trauma' or wounding; the trauma is shared by a group of people, rather than individually experienced; the trauma spans multiple generations, such that contemporary members of the affected group may experience trauma-related symptoms without having been present for the past traumatizing event(s)." (6)

California Native American communities were subjected to multiple colonial regimes and the brutality of the Spanish Mission system. They were hunted for state issued bounties provided by the government in an effort to clear the way for prospectors: 25¢ per scalp starting in 1856, and up to $5 per scalp by 1860. Native women were subjected to sexual violence of epidemic proportions. Children were stolen from parents and put into the brutal boarding school system for reeducation and what amounted to little more than slavery and total cultural erasure. California tribes were cut off from the land that they had stewarded for thousands of years. Both federal and state governments refused to ratify treaties with California tribes, treaties which promised them land that was sacred, land that sustained them, and that held the remains of their ancestors. Healing these harms cannot be done without listening to the stories of these communities, without allowing them the space to express the ongoing trauma, pain, loss, degradation, and feelings of exclusion that still shape their lives to this very day, without respectfully listening to their needs being articulated in their own words.

Portrait of Phoebe Apperson Hearst

Image: California Faces: Selections from The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection

Another important component of the harms done to California tribes falls squarely on the shoulders of UC Berkeley itself, and its illustrious accomplice, Phoebe Elizabeth Apperson Hearst. Mrs. Hearst was a wealthy philanthropist and first female regent of the fledgling University of California. Her vision for the university included an emphasis on anthropology and the sciences, and her money played a key role in the construction of many of the most famous campus buildings and the recruiting of one the university's most famous scholars, Alfred Louis Kroeber. Mrs. Hearst personally commissioned Kroeber and others to lead expeditions that would help to realize her vision of amassing what she hoped would be the greatest collection of artifacts from ancient civilizations from around the world. In Leventhal, Field, Alvarez and Cambra's article “The Ohlone, Back From Extinction,” the authors detail how Kroeber's misguided practices contributed to Bay Area tribes—the Ohlone in particular—being excluded from recognition by the federal government which was required to receive any federal benefits.

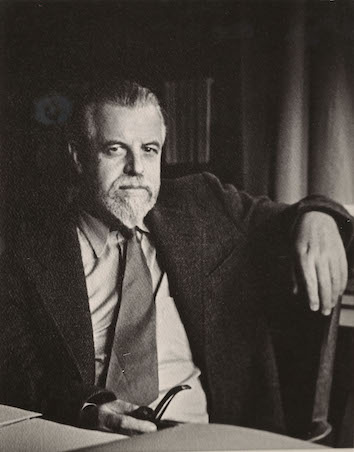

Alfred Louis Kroeber seated at desk, holding pipe.

Image: California Faces: Selections from The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection

"Alfred Kroeber arrived in California in 1901, concerned to describe 'native primitive culture before it went all to pieces', which he believed could be accomplished by treating the surviving descendants of the catastrophes Californian natives had endured as specimens of 'timeless, ahistorical cultural type[s]'. From the point of view of many present-day anthropologists Kroeber did not take sufficient note of the genocidal ventures Europeans and Euro-Americans had conducted against California natives. For this reason he persistently confused fragmented societies and cultures he described with the pre-contact condition of those same societies and cultures." (7)

Kroeber's mistaking of a wounded and devastated society as being in their pre-contact state contributed greatly to the Ohlone tribes of the San Francisco Bay Area being excluded from claiming federal recognition. By distinguishing them as "triblets" and not as fully functioning sovereign nations, Kroeber entrenched them in a category that denied them their rightful status and corresponding benefits. One misguided academic's incorrect assessment of an entire population was all it took for the federal government to turn its back on a suffering population that it still ignores today. Furthermore, the Federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990, and its California equivalent (CalNAGPRA) of 2001, were enacted to protect sacred Native American grave sites and facilitate the repatriation of Native human remains and cultural objects to their tribes from museums like UC Berkeley's Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Despite having had three decades in which to develop a system, determine the origins of various items, and take action to comply with these Federal and State laws, UC Berkeley has repatriated less than 20% of what is known to be the second largest accumulation of ancestral remains in the country, after only the Smithsonian. (8)

Native voices are essential to this process of repatriation, and provide another good example of why the UC Land Grab Report's recommended actions mandate working with California Indian tribes through a "transparent, collective process to pursue actions that meet the priorities of Native communities." (9)

Notes

1. Joseph A. Myers Center for Research on Native American Issues & Native American Student Development, 2021. "The University of California Land Grab: A Legacy of Profit from Indigenous Land-A Report of Key Learnings and Recommendations." University of California, Berkeley.

2. Theresa Stewart-Ambo "The Future ls in the Past: How Land-Grab Universities Can Shape the Future of Higher Education;" Native American and Indigenous Studies, Volume 8, Issue 1, Spring 2021, pp. 162-168.

3. Ibid.

4. The University of California Land Grab Report.

5. Nathaniel Vincent Mohatt, et al. "Historical trauma as public narrative: a conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health." Social science & medicine, Volume 106, April 2014, pp. 128-36.

6. Ibid.

7. Alan Leventhal, Les Field, Hank Alvarez and Rosemary Cambra, "The Ohlone: Back From Extinction," Ballena Press, 1994.

8. Danielle Elliot, Berkeley's NAGPRA Implementation, Federal Indian Law Writing Seminar, December 16, 2020.

9. The University of California Land Grab Report.