Desegregating San Francisco Public Schools in the 1960s

Historical Essay

By Kristina Rizga

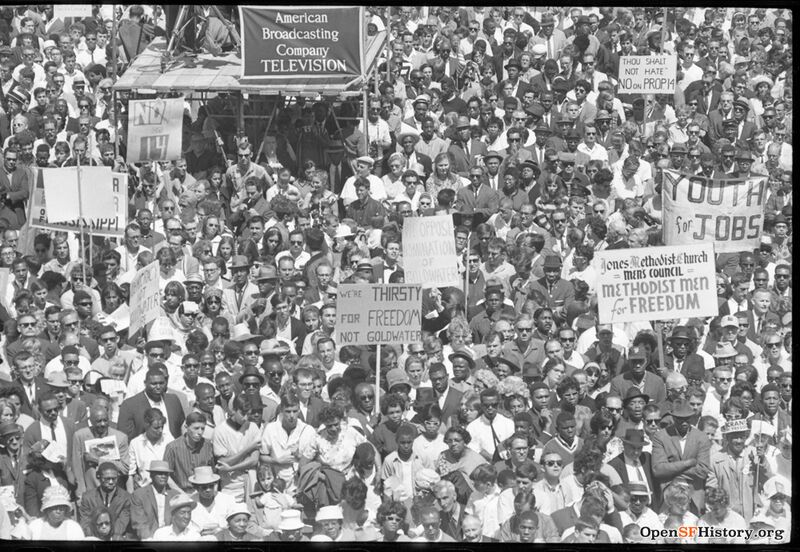

Civil Rights march in Civic Center Plaza, July 12, 1964, part of a large mobilization of San Francisco's African American community protesting job and housing discrimination as well as school segregation.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp28.2260

While organizers in the South were fighting to end apartheid schooling there, civil rights organizers like the NAACP and CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) were protesting segregation of public schools in the West and Northeast; including San Francisco: While the Brown v. Board of Education decision made segregation illegal in the South; de facto segregation was widely practiced in the test of the country, mostly through discriminatory housing policies. Many Progressives on the West Coast, resisted acknowledging that segregation existed and working on solutions, sparking boycotts and lawsuits. A growing number of civil rights groups, parents, and students were also becoming increasingly critical of tracking, which they viewed as segregation in "desegregated" schools. (7)

In the Bay Area, parents of color started to organize for a more equitable distribution of resources among schools. In 1974 in San Francisco, lawyers had successfully sued on behalf of eighteen hundred Chinese American students demanding English as a Second Language programs. Lau v. Nichols was an important court case that, for the first time, made an argument within the context of public education that equity doesn't always mean equal distribution of resources. English learners, poor students, and students with disabilities have different, unique needs, they argued, and equity means providing extra resources and funding to respect their needs. (8) A separate 1976 court case extended these civil rights to nearly 3.7 million students with disabilities. (9)

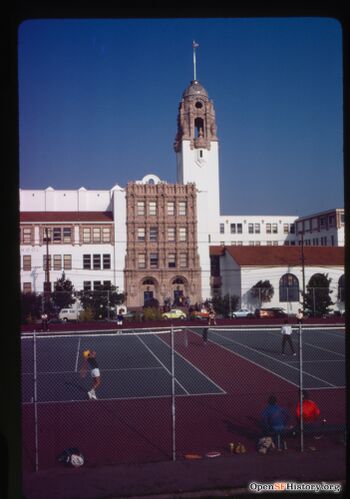

Mission High north of the Dolores Park tennis courts and across 18th Street, 1977.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp25.10692

From the walkouts in East Los Angeles to strikes in Crystal City, Texas, to Detroit, Michigan, some thirty thousand African American and Latino students went on strikes in 1968 calling for new curricula that included the intellectual contributions of Latino and African American cultures, more diversity in staff, and more humane treatment by their white teachers. (10) The new generation of organizers felt that standardization led to an idea that students of color were suffering from cultural deficits, rather than acknowledging that there might have been a mismatch between the culture of the school and the culture of communities. Students of the San Francisco State University's Black Student Union and a coalition of other student groups called Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) led America's longest student-led strike on any campus; it lasted close to five months. Activists' lists of demands called for new classes that would include the histories, philosophies, and sciences of African Americans, Latinos, American Indians, Arab and Muslim Americans, and Asian Americans. The American Federation of Teachers joined the strikers, and as a result of the prolonged stand off, San Francisco State University created the first-ever College of Ethnic Studies, in·1969. Almost two decades after the founding of the College of Ethnic Studies; which created a new Black Studies Department, McKamey, Roth, and their colleagues would enroll in the seminars there that introduced a new generation of teachers to the long history of educational theory and successful practices among African American teachers, such as W. E. B. DuBois; Bob Moses, and Noma LeMoine, among others.

In 1965 President Lyndon Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA)—the most significant federal intervention in education in the twentieth century and a precursor to No Child Left Behind—as part of his War on Poverty, which provided significant extra funding, known· as Title I; to high poverty schools that were historically neglected by the local school boards. David Tyack writes that a great deal of that extra-federal and philanthropic funding in the 1960s unfortunately went to middle-class bureaucrats to administer some new topdown approach that only intensified the same standardized strategy, like remedial classes, rather than allowing teachers to come up with instructional methods and curricula that were more rooted in the cultures and needs of their students. (12) But with this extra federal funding, enforcement, and increased oversight came a growing acceptance of a new role of Washington in state and local education matters. When federal legislators sent extra funding to local schools, they wanted some kind of assurance that this funding was reaching the students and was making a difference. Robert Kennedy was one of the chief advocates for the use of standardized achievement testing to make sure that federal funding was used to help students who were historically neglected. Cuban pins the beginning of the move toward high-stakes testing and accountability to the passage of the ESEA. Anya Kamenetz argues that the instruments that were once created to justify racist practices now became the most powerful tools used to diagnose the wrongs of racism and to fight it. (13)

Notes

7. Larry Cuban, Urban Chiefs Under Fire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 112.

8. Sheila Curren Bernard and Sarah Mondale, School: The Story of American Public Education (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), 158.

9. ibid., 162.

10. ibid., 127.

12. David Tyack, One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974), 282.

13. Anya Kamenetz, The Test: Why Our Schools Are Obsessed with Standardized Testing—But You Don’t Have to Be (New York: PublicAffairs, 2015), 66.

Excerpted with permission from Mission High: One School, How Experts Tried to Fail It, and the Students and Teachers Who Made It Triumph, Bold Type Books: 2015