GET THE MESSAGE: MERCURY RISING HAS RISEN!

"I was there..."

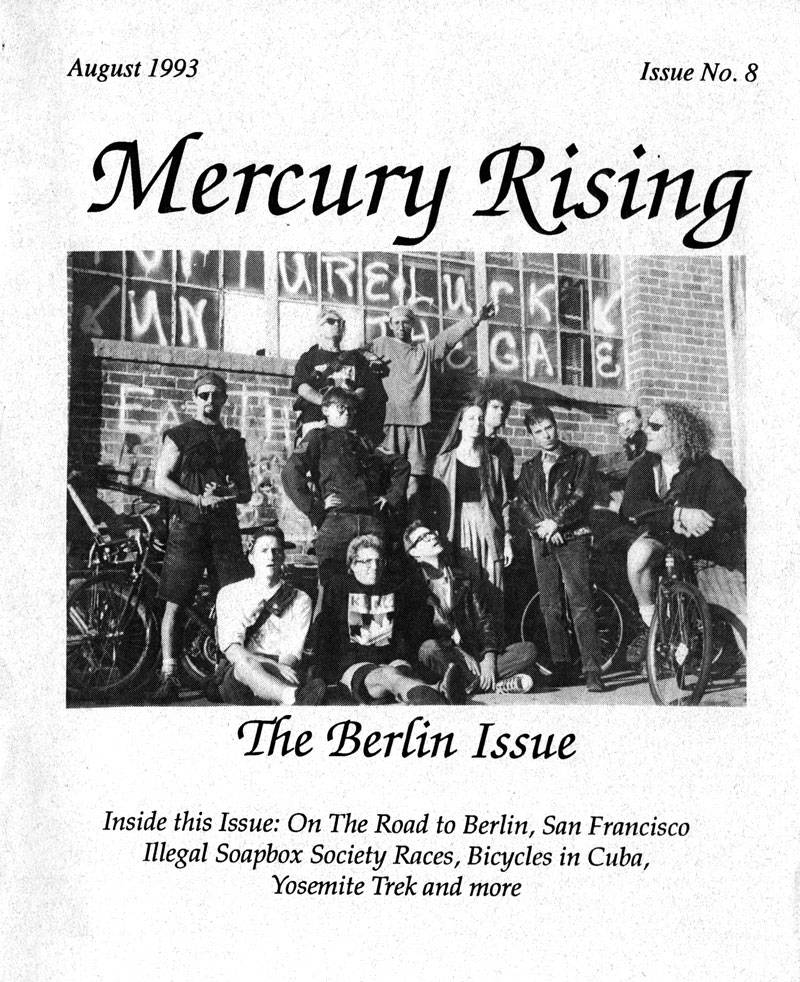

Front cover of Mercury Rising No. 8, August 1993.

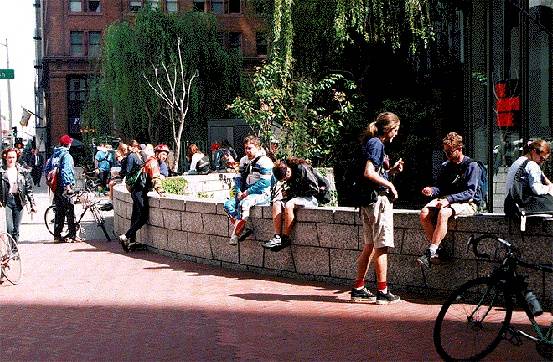

Workday hangout for San Francisco's bike messengers, the Wall, on Sansome between Bush and Sutter, c. 1995

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Mercury Rising cover issue number 16

Mercury Rising

Interview with Markus, Amerigo, Pelona and Ramblin' de Kay -- of the collective that publishes Mercury Rising, a new magazine by and for bike messengers. Interview conducted by Chris Carlsson on January 11, 1992, in San Francisco's Mission district. Originally published in Processed World #29, published August 1992.

Amerigo: Mercury Rising was Markus' idea, really.

Markus: One of the major companies in town, Executive Courier, lowered commission rates from 50 percent to 48 percent, which is a 4 percent paycut, on a couple of days notice. I was down the next morning with a flyer telling everybody to go out on a wildcat strike. It was clear that that wasn't going to be happening. The day after that I had a petition about why management was going to have to give something if they were going to take money out of people's pockets. I don't think anyone signed it and it ended up being a big personal defeat, but it did end up getting a bunch of us thinking. We all talk about work after work.

Amerigo: Yeah, too much!

Markus: We realized that we need something that gives people the nerve, that makes them feel confident enough that they could have a wildcat strike if the time comes, or to do any kind of solidarity action. People have to communicate and in our business there's still quite a bit of turnover, and always a lot of new people on the street. At times it's very much of a community and one big family, but in another way it's pretty atomized, and we have a lot of getting-together to do before we can fight for the survival of our profession, which according to the front page of last Wednesday's San Francisco Chronicle, is threatened with extinction.

PW: It sounds like one of the main goals is the development of some kind of community?

Amerigo: No one is just a messenger. Everyone has outside trips: they're in bands, they do 'zines. This is a way to get all that in, print people's poetry, print people's artwork, you know, spread the word about other people's projects.

Markus: We give everyone a forum to print stuff that isn't directly related to our organizational goals for bike messengers. Still, it's really good for those long-term goals because we are getting together in different areas of people's lives.

Amerigo: MR is the first thing that I've ever dealt with on any level (I've worked at legitimate newspapers, too) where everyone is so enthusiastic. Well, it's waning now, but people keep pouring in their stuff, you don't have to go and beg for contributions. People pay for it, they're excited and happy to see it.

Pelona: People are asking, "Oh, when's the next Mercury Rising coming out?"

Markus: It's amazing how quickly it found its audience, it's like a big success. The first day, the first issue, I'll never forget. It came out late in the afternoon and it was on a Friday. We always try to release on a Friday cuz that's when people are flush. When I got home, my pockets bulging with money, I put it out on the kitchen table and it was eighty-some bucks.

Amerigo: In quarters!

PW: Does working on Mercury Rising make the prospect of being a messenger any easier?

Amerigo: It's like a total immersion in the culture, it's almost too much.

Pelona: I've met so many more people since I've been working on this. I feel more a part of the community now, so I guess I do have more reason to stay in it. I was going to leave San Francisco to go back to college. I couldn't stand my job! Bike messengering, I thought "how can I get out of this?" But I didn't think at all in terms of how can I make this a better situation. I just wanted to personally get out of it, but I see the situation differently now.

Markus: I've always had this romantic fixation on this particular job. It's also convenient for me to do the other things I want to do, like I was able to work part-time and come back full-time in the summer and January so I could go to school for those five years. It's really a great job to have if you're playing music because there's a lot of other messengers who tend to be into music and in bands too.

PW: What makes it a lovable job?

Amerigo: The people involved, they're just the most hilarious, amazing or strange, bizarre people you'll ever meet. The most eclectic collection of individuals ranging across every interest, every intelligence [laughter].

Markus: And age group, we're not all a bunch of young people. There are people raising families on this more and more.

PW: Is it a health choice for some?

Amerigo: Some people do it cause they're into biking, some people just like to stay in shape.

Pelona: I can't sit down for a long time every day. I really need to bike two or three hours a day or I don't feel right. I like being outside. I meet a lot of different people in elevators and I feel really free to make comments about what they're saying, since I'm not going to ever see them again. You're alone a lot of time, you can think about whatever you want, that's the greatest resource of this job. You're doing this thing physically, but your mind is totally free, you can be thinking whatever you want and no one is looking over you.

Amerigo: You get totally addicted to the adrenalin too, a physical addiction. I almost get killed a couple of times a day and get so wired, I'll be jumping up and down. The days when I work and the days I don't work are so different.

Markus: And when it's really happening, like in the last three hours of the day you make like $30 an hour, it's just go, go, go, getting weird waiting time, having incredible luck, and making all this money when you've had a shitty morning or something. It's really fantastic and you feel like you've just been through this incredible adventure, especially when you've done it on acid! [laughter]

PW: Bike messengering has that exhilaration that comes from exertion. You can exert yourself and do better as a result-- that's not true of a lot of work. You're in a bank with this huge stack of paper on your desk. You work extra hard to get through it, and at the end of the day a new stack of paper is on your desk.

Ramblin': Going into so many buildings, it's so stagnant and antiseptic. You deliver your package and you just don't want to be a part of that--it's bad enough to deliver the package!

Pelona: It's true, many times a day you think "oh god, if I quit I'll have to do something like this [office work]." People are all sitting around in these expensive clothes, looking so bored.

Markus: After going to so many offices for so many years you start seeing everyone else's work as "all those jobs," and bike messengers as "your job." You do learn where there are some groovy offices, where people have a good time, but mostly. . .

Amerigo: Then there's places like Bechtel, where you go in and people's bodies are weirdly shaped, sad faces like they're in jail or something, and you go into those rooms where all the computers are, and it's chilled to like 50 degrees, and you think "Oh I wish I could work like this." [laughter]

PW: Do you agree that bike messengering is a dying niche because of fax machines and rising workmen's compensation insurance rates?

Amerigo: No, there are more messengers here than ever.

PW: How many do you think there are?

Amerigo: I've heard anywhere from 200 to 600. I'd estimate around 400-450, that's including scooters and walkers. You just see more than ever and there are new businesses popping up all the time. Definitely the industry is changing. It's moving away from where you have your company bike. There's all sorts of different companies now, and lots of them don't have insurance and that's scary.

PW: So if you get hurt, it's just tough luck?

Amerigo: Yeah.

Ramblin': That's part of a trend among big companies to treat messengers as merely a commodity, and not as part of the company itself, merely a means of landing larger contracts.

PW: So what about the general profitability of bike messengering? Isn't true that the real money is made from the longer-distance truck tags?

Markus: Our boss told us that it costs the same to administrate a $40 vehicle tag as it does to administer a $3 downtown regular.

Amerigo: So raise the rates!

Markus: Our company has far more drivers than bikers. Now Courier, maybe we're up to a dozen bikers now, but we have about 40 drivers, maybe a couple of big accounts like IBM in Foster City. We bike messengers exist for the convenience of their downtown clients. Our company knows they need a certain number of bikes to keep things going, so they're supposedly committed to some people being able to make a living.

A company like Aero on the other hand, is committed to not let anybody except maybe a few make a living. Everyone else is just supposed to cycle through really fast before they find out that they're getting ripped off.

Anyway, about the "dying niche"--such bullshit, because it's been said as long as I've been in the business. In the local and national media the fax has been killing us off as our numbers grew year after year. I disagree with Amerigo in that I think there are finally a little bit less of us than there have been. We've kind of leveled off and the numbers have tapered a bit, and are likely to taper further, but that's not necessarily a bad thing for us. Those tapering numbers could indicate less rookie turnover and more stability and getting our business institutionalized. We can't make any progress as far as not being ripped off, as long as people are living under this useful illusion that we're on our way out.

One of the main things we have to accomplish is to show ourselves, and the rest of the people out there in the City and the rest of the Bay Area that they should think of us as permanent, because there's going to be hundreds of us out here for a long time, and we should have the right to survive our jobs and not be killed.

In future issues we have to have some kind of broad exploration on "Is the Messenger Business Dying?" Since the controversy has been newly brought up. I think messengers haven't analyzed stuff that much yet, and kind of believe it, so we need to go public with a basic "why messengering isn't dying out."

PW: And also why they're saying it is. .

Markus: We're happy to make three bills a week.

Amerigo: I'd be ecstatic! I don't make that much.

Pelona: My last paycheck was for $230 for seven days' work.

Markus: That's an interesting dichotomy because we're all involved in the same thing but because of the seniority system in our industry we're not really in the same boat economically.

Pelona: One thing I don't like about messengering is that it makes you competitive with your co-workers, because there's a certain amount of tags and some of them are good and some are shitty, and some people are going to get gravy and some will get shitty tags, and you want to get the gravy. If you're working somewhere and they hire some more people, you can hate this person for like 2 or 3 days who's causing your paycheck to go down (not really of course). Until you meet them and talk to them and then they're just like you.

Markus: I get to do this legal stuff, but I'm not the number one guy. They set up a pecking order and if we want our part in it we generally don't say anything. I got set up in a weird political situation because I'm in the "Inside Club," those who are trained, in other words taken around by Joshua and shown how to get into the computers and the courts and stuff, introduced to docket clerks and shit like that. We get 40 percent for doing jobs for this legal subsidiary company. If I'm doing just that work I can do that and no other tags for the normal company, but the way it is being #2 I just get it sometimes. I make 40 percent but if it gets too busy and they have to spin some of this work off to the regular Now riders, they make 30 percent. I sounded off about this and threatened to forego my position, but I ended up capitulating, although I continue agitating for them to get a higher percentage. We get a lower percentage for legal work because there's a lot more work in the office processing this stuff. I have no problem making 40 percent. I guess there's some logic for there being some "club" that does it, that is mostly just a few people. But it's all pretty uncomfortable. It puts a strain on solidarity, no question, because I need all the dollars I can get.

PW: Especially in this economic climate! It's like musical chairs, and I'm in a chair and I'm staying right here, I don't care if they start the fucking music! [laughter]

Markus: We're in a business where there's more sophisticated technology, the fax, which can ostensibly do what we do better and cheaper, if you're only doing one or two pages. And then there's cars, an inferior technology, that can also do our job, and they're saying it's a superior technology. I'm sure there are niches for us like big clients that will go on needing the kind of service we provide.

Pelona: Another person was telling me about public-key encryption that allows documents to be sent between computers with a code that is as good as a signature. He told me that when this takes over it will eliminate some messenger business, because things like court filings that would need a lawyer's signature that we currently hand deliver will be able to be sent by modem. And as the recession gets worse, a lot of the stuff we deliver is sent by messenger for the prestige of a "hand- delivered" letter via messenger, and people are just going to fucking put a stamp on it when they're cutting costs.

UNIONS AND INFORMAL ORGANIZING

PW: What do you think are the advantages of a more informal approach to organizing versus something more traditional and formal?

Ramblin': I think it's more enjoyable, so you spend more time on it, it's more sociable. The amount of effort you put into something is related to what is going to come out, and if you're working in these rigid, bureaucratic structures you're just half-assed about what you're doing.

Pelona: I belonged to the California State Education Association (CSEA) and the only thing I ever got out of it was a discount on ice skating.

PW: How old were you then?

Pelona: 18.

PW: So you were just out of high school. Did you have any notions of the noble struggle of labor, or that you ought to belong to a union because that's what you do when you're a worker, or any of that kind of stuff?

Pelona: The reason I joined is cause I was working in a school and then I got a job as a secretary for the teacher's union, and I felt so bad, here I was working for the teacher's union and I wasn't even a member of my own union, so I joined.

Markus: We have a union shop in town, Express Messenger, a Teamsters shop. They're covered in issue 4 of MR. I worked there when they were one of the big companies in town with 30+ bikes, and was there for some of the struggle to get the Teamsters in. One of the reasons why bikers are a little reticent union-wise is that the Teamsters haven't particularly worked out for Express.

Amerigo: Wouldn't you say that Express, along with Aero, is about the worst-run, most inefficient company, and treats their messengers the worst of any company?

Markus: Yeah, except that I would disagree about Aero, because it's well-run for the evil purposes to which they are directed.

Pelona: Express is just incompetent.

Markus: It really is, and I think they blame unionization for some of it. I think with messengers it would have to be a brand new, independently started thing that would have to take the form that people wanted from it.

Ramblin': I didn't mean to hit too heavy on organized unions, I really do respect people who can work within that context.

Markus: Oh yeah, unions are really big in my family. My dad is an IBEW man, he works at the Nevada Test Site on nuclear bombs, and my great-aunt was a big union organizer, too, on my mother's side. It's always been clear to me that workers should be organized.

Mercury Rising is an unofficial publication of the San Francisco Bike Messengers Association. There is no "official thing" of the SFBMA--

Amerigo: It's sort of an anarchist labor organization.

Markus: Yeah. It's a disorganization at this point. It's evolving.

Markus: I think the San Francisco Bicycle Messengers Association was started by Rich and Nosmo, the people from the other messenger magazine, MessPress, which you really must pick up. It's less political, but very cultural and joyful. About individualism, you were asking? Going independent is one of the big trends, and for a lot of people it may be the solution to our labor problems.

Amerigo: There's so many jobs, there's this big hype in America about this supposed work ethic, but it's so hypocritical. They're not working, they're just sitting there. That's why I'm proud to work commission. I only make money when I work. I don't sit on my butt and get paid hourly.

Pelona: We work really hard. I don't know if we said this, but. . .When I worked at Sizzler I worked really hard, but this is the hardest job I've ever had, the hardest money I've ever earned.

Markus: Your labor is less alienated when you can feel how much you're making by how much you're working. Standing-by gets stressful if you do it too much, 'cause you go "fuckinnotmakin'anymoney!!" But generally you don't have to feel guilty about standing by, lots of time you just wanna staaaannd byy [laughter].

Pelona: Once you start standing by you just want to keep on standing by.

Markus: Oh, when we're at the Wall, with friends and "proj," man the social life is just great!

PW: You talked earlier about wanting to make things more stable. . .how does the transiency among messengers affect you editorially? Does it cause you just to think to the next issue, or are you beginning to plan say, 12 issues down the road, what you will be publishing?

Pelona: I've been thinking about this because officially I'm on leave of absence from UC Santa Cruz and I told them I'd go back in the fall. Right now we're using Lydia's computer which is at my house. But I'm sure something'll happen, it'll keep going.

Amerigo: You're asking about transient people?

PW: One of your goals is to establish some kind of community of consciousness amongst people employed in similar situations, and there's been sentiment expressed for making it more permanent, more regularized. So transience has a subversive impact on those kinds of goals, doesn't it?

Amerigo: Even though it's bad that we're so disorganized, there's still good things about it. As far as messengers goes, there are a lot of them who've been on the street, lots of people who get off the street by being a messenger, and also people who end up on the street after being a messenger. Even though this is anti our labor goals of getting more money, it's still a place where you can get a job, even if you just got out of jail, even if you've got weird drug habits, even if you drool all over yourself and don't make any sense [laughter].

Pelona: People accept you.

Markus: I think that has already been sacrificed. On KPOO they asked me about messengering as a job for people just entering the market, and I realized that it's already gotten a lot more difficult to get in. Now veteran messengers who've left town, come back and have to wait around a while to get a job. There's just not as much transiency as there was, but still quite a bit, maybe 100 a month!

Pelona: This dispatcher who used to work at Express told me what happened when Express took over US Messenger. Apparently US had been a cool place to work, according to him, a lot of people who had been there for a while were making 55 percent or 56 percent commission, good money. But the messengers had a lot of say in how they would do what they would do. He told me they worked out a compromise between what needed to get done and how they wanted to do things, and the work got done, but everyone had fun and they got to be their own freaky personalities. When Express took over the new management wanted it run like a regular business, and they got rid of all these older people who were troublemakers, and they didn't cut slack for messengers' personalities, they didn't like it when people called in sick. Well the reality is, you can't ride 8 or 9 hours a day really hard, every single day. You physically can't do it. You have to call in sometimes, you have to take breaks. They didn't understand that. He told me, the end of US was the end of what being a bike messenger was about, being a freak, and still getting the work done.

PW: I find this strong affirmation of subcultural identity, of being "freaky," and an embrace of a classic work ethic a curious combination. A lot of times subcultures, especially around the music scene like the outside life of some messengers, are really anti-work. Yet the people doing bike messengering, at least you guys, are asserting a commitment to hard work, that you really want to earn your pay.

Markus: I don't mind that. If I got paid decently I could work 3 1/2 or 4 days a week and do the same job, if I could survive on doing three good 10 hour days, the kind of days I normally work five of, like I would work harder because I would only be doing 3 of them. Boy, I would never look for another job, it would be great. Really, for those of us playing music, that's not anti-work either. It's another job. So's this publishing stuff. Lots of messengers are working incredibly hard on all kinds of things after those 10 hour days.

Amerigo: As work it's fun, it's like a sport.

Ramblin': We talked at the start about the attempt to create some kind of community. I felt that [sense of community] since I came over here [from England] and starting working as a messenger. I've met people who are so honest. They're interested in you if you want them to be. If you wanna bug off on your own and not talk to anyone, they're not going to hassle you.

Pelona: I never felt like I was a messenger. Then I deformed my bike with a basket, decided I was a messenger, and started going out more and getting involved.

Markus: She gave her bike a sex change. [laughter]. . .The fact of bike messenger subculture, I postulate, may be a key reason why they keep wanting us to be a disappearing occupation. Every other industry in this town whose numbers are maybe off 10 percent from what they've been through the '80s, they're not talking about those occupations disappearing. Why are they talking about us that way?

PW: Solidarity in the face of bike theft is described in exciting detail in Mercury Rising. What other kinds of solidarity do you experience and can you foresee among bike messengers?

Ramblin': I think the benefits [concerts and parties].

Amerigo: Messengers came and donated money to get in, and bought beer and wine to help this guy out who got busted for some bogus drug charge.

Markus: About half the gigs my band (L. Sid) has played have been messenger benefits. We had another one at Brave New World where Ramblin' works as a DJ Sunday nights. He's having a monthly benefit, like for a couple of messengers who cracked up off the job and missed some work time as a result. Of course no one's got health insurance.

Pelona: There are so many people who get hurt, we could do a benefit every week easily.

Amerigo: Right now Harvey's [5th Street Market] is our Corporate Headquarters!

PW: You've spoken with distance, if not disdain, toward the average office worker with whom you interact on a daily basis. My impression is that there is a similar, de facto dissidence among temps, in spite of the fact that it is often invisible. There are a lot of temps with an "Attitude." I wonder if there are any practical links between messengers and temps?

Ramblin': I know a couple of messengers going out with secretaries. [laughter]

Markus: No, not much going on in that department yet.

Pelona: A temp is someone who says, "What, a package? Ana L.? I don't know her extension!" That's our take on temps.

Amerigo: We don't have an Inside Contact this month. That's one thing we're trying to do is build a bridge between office people and us. Originally it was Dog of the Month, but we thought that would be pretty bad.

Pelona: I was talking to some people and they said "Well, you've already covered all the good people" in three issues. They said, "You should have "Asshole of the Month!"

PW: Zoe Noe, when he used to messenger for Special T, he gave out a lot of Processed World propaganda, like the Bad Attitude Certificates. . .

Pelona: [reading the bad attitude certificate] oh, but stealing time, when we steal time we steal our own time, y'know?

PW: Do messengers discuss the purpose of the work they do and what kinds of thoughts prevail?

Pelona: We do a run for Citicorp. Our dispatcher has nicknames for certain runs, it's called the ShameOn run--

Markus: SHAAAME ON CITICORP. That woman, I forget her name [she's been picketing a downtown Citicorp in SF for 2 years over some loan fraud she suffered.] There's the Chickenbutt and the Bonehead, these are dailies, the American Dream Run. Pelona: There's a woman named Lynn Breedlove who I interviewed in the second issue, who started her own company, Lickety Split Delivery, but won't go out for corporate clients because she doesn't want to work for Bechtel. The clients she pursues are tenants and legal aid groups, non-profit companies, and so on.

Ramblin': I think your day job, whatever you're doing for money, it might be useless, but you still have this job where it doesn't destroy your other energies, and you have space to do whatever your particular interest is.

Markus: It can destroy your physical energy sometimes, make you a little too exhausted to do as much as you want to do, but you don't have to compromise yourself too much to do it. Another thing, you get to learn a lot by being a messenger.

Pelona: I've been bothered by the meaninglessness of this and really wished I was doing something meaningful.

PW: What is utopia, or at least a society worth fighting for, for you?

Pelona: A society worth fighting for? In utopia, there's no cars. Down the middle of the street, we're gonna tear up all the asphalt and there's gonna be gardens and orchards and you can just grab a peach as you're riding by. Everyone's gonna work 20 hours a week at a job they find meaningful, and they can change jobs throughout their lives if they want to. And everyone is gonna get taken care of, maybe no one will have a lot of stuff but everyone will have shelter, everyone will have food--

Markus: No one will have to worry about getting sick.

Pelona: Yeah, if they get sick they'll be taken care of.

Amerigo: People will care for each other, they'll understand.

Pelona: Yeah, we'll have a feeling of community. You'll be able to walk everywhere you need to go, you really don't even need a bicycle. There'll be like small stores. . .

PW: So a high level of self-sufficiency in local areas?

Pelona: Yeah, so you know people.

PW: Any ideas about how you'd relate to the larger world?

Pelona: No, the whole world's gonna be like that!

Amerigo: We'll all have separate worlds!

Pelona: Someone else was talking about this, they were saying "let's drive all the big corporations out of downtown," but I said "oh no, there won't be any bike messengers," but they said "yeah, but bike messengers are going to be planting gardens and tearing up the streets and stuff."

Amerigo: People need to be honest about their needs. You won't be repressed about things, and you won't deny things like death, you'll understand that there's a cycle and the whole of life will be accepted in balance.