Intercollective

"I was there..."

A Documentary Memoir by John Curl

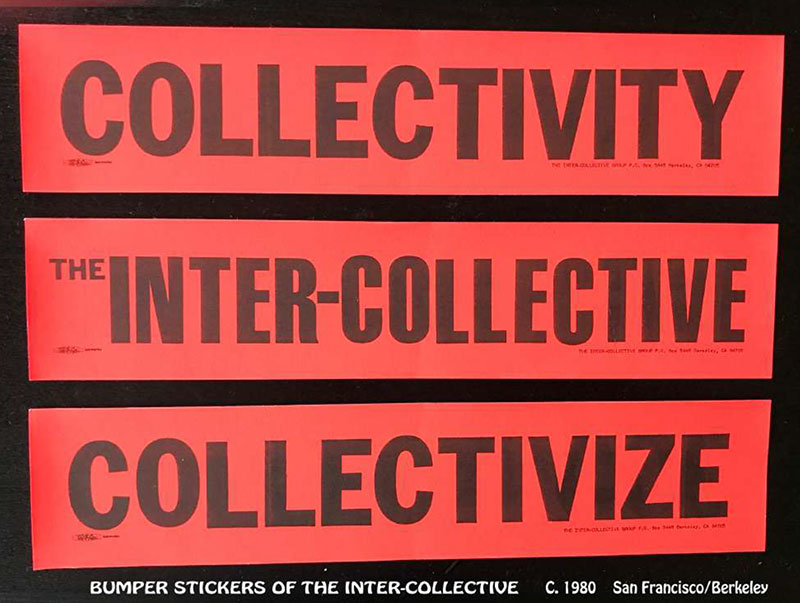

Between 1980-’86, the Intercollective (IC), "an open participatory group of people who are members of collectives and cooperatives," was the meeting place of the Bay Area worker cooperative/collective movement. We met monthly on alternating sides of San Francisco Bay "to socialize and to discuss projects to support the movement." The Grapevine/Collective Networker, a monthly newsletter, reported activities, published articles about the movement, and printed minutes of meetings. Sometimes we spelled Intercollective with a capital C. Projects of the InterCollective included four editions of the Directory of Collectives 1980-’85 and Collective Conferences in 1981 and ‘82. In 1982 we also participated in the Livermore Action Group (LAG) blockade of the Lawrence Livermore nuclear weapons laboratory. We held a class and workshop series in 1983; a Collectives Fair in ‘84; a Community Class series in '86.

Intercollective at Livermore during the 1982 blockade.

Photo: John Curl

The Statement of Purpose (1981) defined the InterCollective as "formed for the following purposes:

- to promote and support collectives, cooperatives, communes, and networking and exchange among them;

- to provide a forum to facilitate exchange of information and ideas concerning them;

- to work for the right of all people to self-manage their work situation, and to collectively own and control their means of survival;

- to promote collectivity as an integral and organizational part of the movement for progressive social change;

- to work for a society free of oppressed classes and not dominated by the commodity form of exchange or the wage-slavery form of work organization;

- to support the development of appropriate technology, for human needs and the protection of the natural environment;

- to support the struggles against imperialism, racism, sexism, homophobia, ageism, and all other forms of oppression;

- to oppose war and the proliferation of nuclear power and arms; and to promote recreation and socializing among members.

The InterCollective did not spring forth full blown in 1980, but grew from seeds planted four years previously, by a group of members of collectives who in 1976 began a project of networking, compiling and publishing a Directory of Collectives, since many groups did not know of each other’s existence.

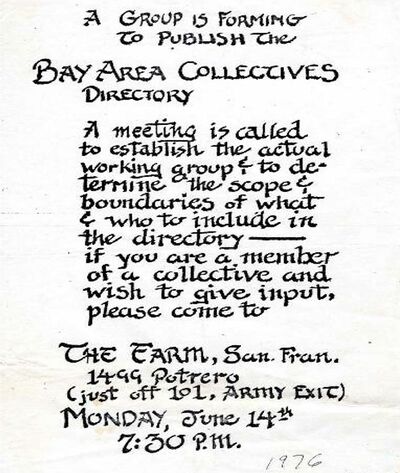

For me it began early in June, 1976, when my shop, Heartwood Cooperative Woodshop, received a nicely calligraphed note, seen at left.

The Farm was a community center under the freeway interchange of Highway 101 at what is now Cesar Chavez Street. I had been there before for some poetry readings.

When I entered someone handed me a sheet titled, "A Brief Introduction to this Meeting," which explained that it had been organized by a group consisting of workers from the Cheese Board Collective (Phil, Moe, Renate), the Juice Bar Collective (Ann), as well as a visitor (Eric) from Riverside Cafe in Minneapolis. It continued:

WHAT PRECEDES IT:

- - Years of discussion in the Cheese Board Collective about our lack of explicit political direction; a need for some of us at the Cheese Board to get in touch with other collectives.

- - A realization that there is in fact a fairly cohesive S.F. food system which has recently begun a discussion on the need to go "beyond isolation."

- - A specific Cheese Board meeting at which $1500 was allocated to further information about and a dialogue among collectives.

- - A meeting with Free Spirit (Ken, Sue, Peter) and People’s Refir (Peter) at which it was suggested that a first step towards communication is to publish a directory.

- - A meeting with the collectives discussing merger; positive response to our proposal resulting in our meeting tonight.

I had heard about the People’s Food System but I had not had direct contact with them beyond being a customer, since my shop, Heartwood Cooperative Woodshop, was not in the food industry. Neither the Cheese Board nor the Juice Bar was involved with the People’s Food System, despite the food connection. The Cheese Board store in Berkeley had been founded by a couple in 1967, and transformed into a worker cooperative in 1971. The Juice Bar was started in early ‘76.

At the meeting were members of ten local groups: besides the Cheese Board and Juice Bar, were Earthwork (land and food education/organization), the Swallow Cafe, People’s Refrigeration, Free Spirit Press, Grassroots (newspaper), Resolution/Newsreel (film distributors), Red Star Cheese (distributors), and myself from Heartwood. Earthwork, connected with the Center for Rural Studies, had their office at the Farm, and was the host.

I chatted with a few people I knew and waited for the meeting to start. Sue from Free Spirit Press gave me a copy of "Beyond Isolation," a pamphlet by a member of Los Truckaderos, a trucking group that operated between the Bay Area and Seattle. She also gave me a paper titled "Statement on Merger," dated the previous week. This explained that there had been a conference a month earlier of the People’s Food System, in which a presentation on "economic merger" had been given. The collectives who responded favorably had decided to meet "to discuss our mutual concerns." The groups listed were Red Star, Merry Milk, People’s Refir, Free Spirit, Earthwork, and Left Wing Poultry. Following that were ten "Points of Agreement," and statements on "Reasons for Merging" by three of the groups.

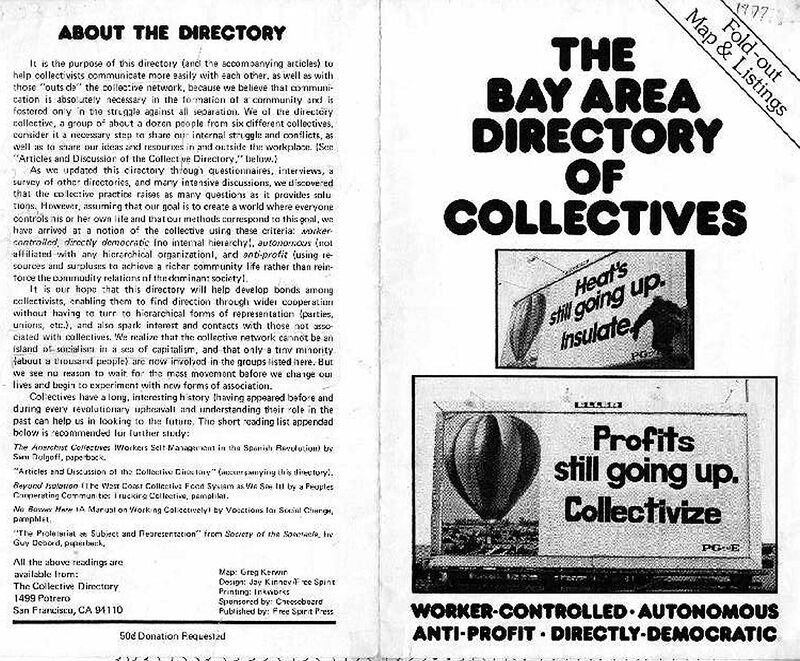

That meeting led to further meetings, and later that year (1976) we published the first Bay Area Directory of Collectives, a two-sided 11" x 17" wall poster. On one side we listed 124 groups under the categories of arts, childcare, counseling, education, health, media, political, restaurants, services, stores, and support collectives, with subheadings of dance, theater, bookstores, schools, graphics, printing, publications, radio, typesetting, video, housing, legal, transportation, woodworking, and food production. Near the top of the far right column were the words, in red letters: "The following groups, including non-food support, have consciously worked toward communication and shared resources under the name Bay Area People’s Food System." Beneath that were 25 group listings: ten stores (seven in San Francisco, two in Berkeley, one in Oakland), thirteen support collectives, and two groups doing food production.

On the reverse side of the poster we printed a cartoon of a worker with a boss on his back, and beneath it:

This Directory of Collectives is being produced by an ad-hoc group from this listing, who feel isolated from other worker-owned/non-hierarchical organizations. We wish to bring together individual collectives, to increase communication, to share skills & services, & to further economic co-operation. This leaflet is a call to respond. The list is far from complete...We plan a more complete directory with information on specific collectives & more general political & organizational issues relevant to these groups.

We asked responders to contact us through Earthwork, and we distributed the Directory to all the groups listed. Not long after, Earthwork received a critical letter from Turnover, the Newsletter Collective of the Food System and asked to be deleted from the Directory:

At the last Representative Body meeting, a letter from Paul at Earthwork was passed out with a Bay Area Directory of Collectives. We feel that some criticisms of this directory have to be made. In the first place, our permission was not asked for our collective to be listed on this directory. This stems from the false assumption that all collectives would like to be listed together. Yet collective is never defined by the directory. Worker-owned, non-hierarchical is on the back, but we do not accept this as a definition of collective. A business run by a group which shares the income and decision making is not a collective. To call any group who does this a collective is to co-opt in a dangerous way the inherent political content of the word collective... If we were to approve of such a directory, we would list ourselves with political, educational publications, and with the Food System... In fact we would only want to be on a list of political collectives, as we do not recognize the existence of a non-political collective.

I was surprised by that response, but others who had been involved in the Food System meetings understood how politically volatile the atmosphere had become. The Directory Collective responded apologetically and in a newsprint booklet of articles accompanying the next Directory, we printed the exchange of letters with Turnover:

The intention [of the first Directory]... was to gather information to publish a more realistic directory of collective activity in the Bay Area,... to find ways to increase cooperation among collectives on economic, organizational, political grounds, and further to discuss (for the purpose of raising awareness) these basic questions of what a collective is, what political consciousness has to do with it, and what education is needed... (Y)our request to be deleted from any further directory will be respectfully acknowledged.

We received only positive feedback from all the other groups, so we proceeded with the project and worked on an expanded edition of the Directory, to be published in the summer of 1977.

The 1977 Intercollective Directory

Meanwhile, conflicts in the People's Food System came slowly to a head, culminating in an All-Worker conference in April, 1977, which was called to resolve issues and organize the Food System on a stronger level, but the conference dissolved when outside in the parking area a shoot-out between rival prison groups left the leader of one group dead and the People’s Food System in a state of collapse. Activists from the prisoners movement had been working in the Food System, and with them came prison group rivalries, and almost certainly a police presence.

The collapse of the Food System left the Directory as the only group organizing cooperation among Bay Area collectives. A few months later, we published a revised Directory, an 17" x 24" double-sided poster with 141 groups listed. In a newsprint booklet of articles which accompanied that Directory, we focused on dialog about "the experience of working in a collective and their role in social change."

The 1977 Directory was well received, both by groups that had no connection with the Food System, and by groups that survived its demise, so we set to work on an expanded edition, to be published in 1980. Members of collectives began meeting regularly, and these meetings became the Intercollective.

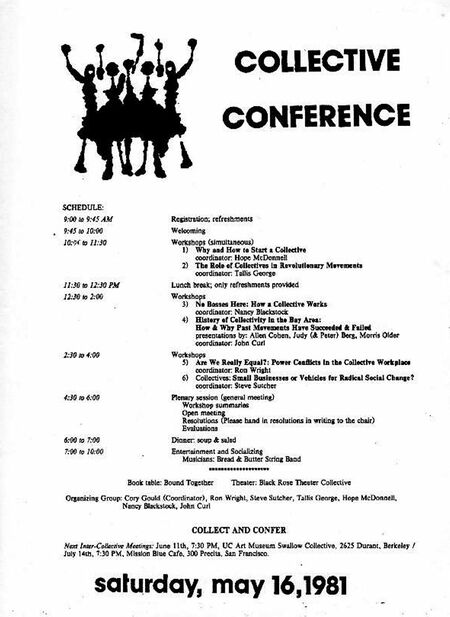

At the first Collective Conference, on May 16, 1981, organized by the Intercollective, I facilitated a workshop entitled, "History of Collectivity in the Bay Area: How & Why Past Movements Have Succeeded & Failed," with presentations by Allen Cohen (communes and the Oracle newspaper), Judy and Peter Berg (the Diggers), and Morris Older, a baker from Uprisings Bakery in Berkeley, who spoke about the People’s Food System. This was the first time that any former participants in the Food System publicly discussed the events of April 1977, four years earlier. The purpose of the workshop was to try to put those events into perspective and begin to heal and move on.

To better understand this history, we need to pause and examine its historical context. The key date is April 30, 1975, the fall of Saigon, essentially ending the Vietnam War. In the late 1960s and early ‘70s, the lives of a generation of young people were deeply distorted by the Vietnam War. Drafted into the U.S. Army, large numbers refused to fight, unwilling to sacrifice in what they considered an unjust war. As the anti-war movement grew, so grew a community of young activists and radicals, who turned to each other for support, together tried to live by different values, and tried to reinvent society through cooperation, sharing, and direct democracy. It was a spontaneous national movement, and the Bay Area was a center of activism.

I lived in San Francisco the summer of 1966, and participated in the great spirit of collectivity that pervaded the air and came to be called "the counterculture," centered around Haight-Ashbury, an inexpensive neighborhood at that time, and across the Bay in Berkeley. The first issue of the Oracle newspaper came out, a multi-colored newsprint that helped organize the spirit. The Diggers had no structural organization at all, just a handful of people initiating projects such as the free store and free food distribution, that large numbers participated in.

The following two years I lived in Drop City, a rural commune and art colony in Colorado. Then in the fall of ‘68 I moved to New Mexico, where I worked on the Navajo reservation and later in an Albuquerque cabinet shop.

I returned to the Bay Area in 1971, and soon joined the woodshop of Bay Warehouse, a collectivized industrial complex in West Berkeley, with a print shop, an auto repair shop, wood shop, pottery shop, as well as a theater, worm farm, darkroom, and other activities. The collective members shared all our income and paid ourselves according to need, which was obviously pretty problematic. Bay Warehouse Collective was also the local weekly distribution point for the Food Conspiracy, a network of food buying clubs, which had grown quickly and involved a large number of people. The Oracle and the Diggers were gone from San Francisco, but now there was a publication about collective living, Kaliflower, hand printed on nice paper, and distributed free to group houses (and only to communal houses; it was not for sale).

Kaliflower appeared regularly for a couple of years.

But at that time there was no organization or publication among work collectives. The Food Conspiracy was the main network, and it was concerned primarily with providing an alternative to Safeway. But it relied on the boundless energy of an organizing group, and when they burned out after a few years, so did it. Many of the main people from the food conspiracy went on to form collective businesses related to food.

Many people on both sides of the Bay were forming "collectives" for every imaginable activity. A "collective" was a non-hierarchical organization, a flexible concept which could take a variety of forms. Different groups applied collective organizing in different ways to different activities, including creative and social justice work. Groups doing productive work were basically worker-owned start-up businesses. Most were started on a shoestring, with volunteer, underpaid or unpaid labor, with the hope of becoming able to make a sustainable living doing constructive work in a healthy work environment. That was not easy to achieve, but it was where the rubber hit the road.

Ma Revolution natural foods store in Berkeley was founded in 1970. The original owners of the Cheese Board (started in ‘67) transformed it into a worker cooperative in 1971. Seeds of Life/Semillas de Vida and People’s Bakery were started in San Francisco in 1973.

These were the years that the Vietnam War was slowly and painfully hurtling toward its conclusion.

In addition to the Food Conspiracy, Bay Warehouse Collective was in touch with the larger movement for social change through our print shop, which primarily did "movement" printing. Bay Print Shop worked for many progressive causes, including the Farm Workers Union, as well as printing the first edition of the book, Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism, by the Weather Underground.

But Bay Warehouse Collective was hit hard by a wave of gentrification in the industrial zone of West Berkeley in ‘72 and, after struggling for two years, folded. The woodshop, print shop and auto shop collectives all relocated and continued separately. Bay Printshop became Inkworks. Bay Auto Shop became Carworld. Bay Woodshop reinvented ourselves as Heartwood Cooperative Woodshop in 1974.

At the same time, in 1974 and ‘75, many other work collectives were forming in the Bay Area. To understand why, consider the context. When Saigon fell on April 30, 1975, essentially ending the war, the community of young people who had become antiwar activist dropouts briefly celebrated, then took a deep breath and realized that they could now get on with their lives. This was their opportunity to do things differently. They were getting older and turned their attention to making a living, improving their personal relationships, finding a career, having families, and rebuilding the world into one they wanted to live in. Almost immediately, women’s issues arose, and issues of racism, which led Ma Revolution to institute affirmative action policies.

In late 1974 a group of the San Francisco food collectives rented a storefront at 3056 24th Street, "originally conceived as a community center for information and meetings," and began publishing the Storefront Extension newsletter, "a communication tool for the cooperative food system," which later became Turnover. In 1975 workers in various Bay Area food groups began meeting in what they called All-Coop meetings, particularly those interested in organizing closer ties toward the vision of a People’s Food System. In April ‘75 they elected a Representative Body. In the same period, many Food System people were involved in the ongoing struggle over the International Hotel. Conflicting visions of the structure and the goals of the Food System emerged. They held a conference on racism.

The dramatic rise of the People’s Food System in 1975-’76 out of the Food Conspiracy and the natural food movement, began as an inspirational story of people banding together to reshape their world. Many radical visions, ideas, and tendencies were competing in the Food System, reflecting the political climate, and ideological struggle filled many of their meetings. Under ordinary circumstances, those forces and contradictions would have continued to compete and sort themselves out. But these were not ordinary circumstances. The events of April, 1977 are still debated today, and continue to have repercussions.

The life of the Intercollective coincided with the years of Reaganism. When Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, the political climate in the US took a sharp right turn. Over the following years, many collectivists became discouraged. As the 1980s progressed, attendance and participation at Intercollective meetings slowly diminished. The Community Class series in April 1986 was the final project, and after that, the Intercollective ceased to meet. The Collective Networker continued with a small core group for another year and a half, centered around Geoph Kozeny, Mary Carlton, and Paul Kumli, and published the last Networker, Issue 115, in January, 1988.

The Intercollective died a natural death. Collectivity in any society always rises and falls in waves under different economic and political conditions, and at that moment interest in collectivity had diminished to a low point. People simply stopped coming to meetings.

The 1988 last issue of the Collective Networker newsletter.

In the following years, there was no organization in the Bay Area actively organizing cooperation among worker cooperatives and collectives. However, many cooperative and collective groups continued, and eventually new ones began to be formed again.

Finally, in 1994 workers representing nine Bay Area worker cooperatives began meeting again to address their isolation, and formed the Network of Bay Area Worker Cooperatives (NOBAWC), which remains active today.