San Francisco Bay Area People’s Food System

Historical Essay

by John Curl, Part Four of an excerpt from a longer essay “Food for People, Not for Profit: The Attack on the Bay Area People’s Food System and the Minneapolis Co-op War: Crisis in the Food Revolution of the 1970s”

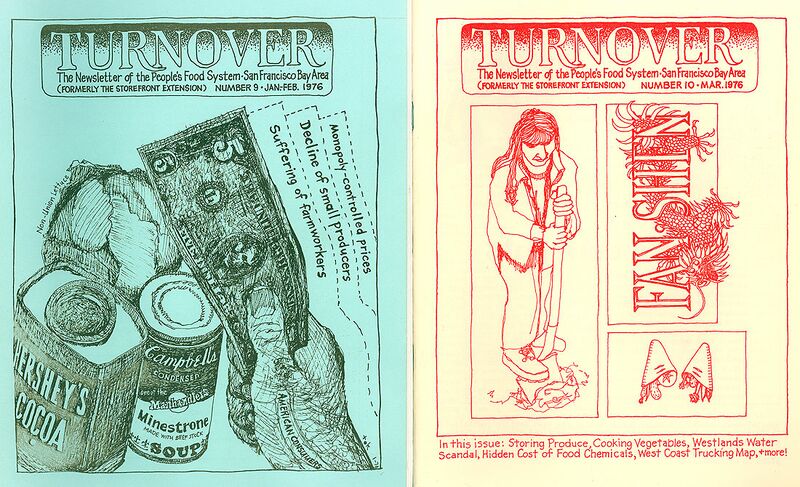

Covers of issues 9 and 10 of the People's Food System newsletter called "Turnover."

- Children of the future age,

- Reading this indignant page,

- Know that in a former time,

- Love, sweet Love, was thought a crime!

- —William Blake

The San Francisco Bay Area People’s Food System (PFS) was a spontaneous movement arising out of the forces set in motion in the Food Conspiracy. However, all social movements need a spark. In this case the immediate spark bounced from San Francisco to Minneapolis and back again.

In 1970, several young friends from the Midwest lived in San Francisco for a few months and were inspired by their experience in the food conspiracy. When they returned to Minneapolis, one of them, Susan Shroyer, organized a bulk foods distribution depot on a friend’s back porch. Others became involved and in 1971 it developed into North Country Co-op. From there it sprang into a thriving movement of autonomous neighborhood co-ops.(19)

The earliest Minneapolis food co-op stores were organized essentially the same as the San Francisco Food Conspiracy, with no formal structure and run entirely by unpaid volunteers. As they grew, they developed legal structures and a common wholesale and distribution system, Minneapolis People’s Warehouse (MPW), which broke away from North Country and became autonomous during that co-op’s first year, in 1971.(20) The warehouse at first used volunteer labor, but needed greater organization, and was soon run by a collective of the workers. Step by step Twin Cities activists developed a concept by which the core group of each neighborhood co-op—each worker collective—would take over the running of the store, supplemented by volunteer labor, and would start getting paid as soon as that became economically feasible. Each core collective was small enough to run through direct democracy. The basic idea was a network of nonprofit collectives running stores and support groups and getting paid for their work. Paying the workers was needed to keep the project alive but was not the primary goal.

From Minneapolis the idea bounced back to San Francisco. Three young people from Iowa—Mark Ritchie, Margie Keller, and Betty Carlson—who had lived in Minneapolis and participated in the co-ops there, traveled to San Francisco in 1972. Seeing the limitations that the Food Conspiracy was going through, they thought that the Minneapolis concept could be successful here too. They connected with a neighborhood food buying club run out of St. Peter’s Church on 24th Street, one of the main drags in the Mission district, a Latino and working-class neighborhood. With the help of Father Jim Hagan, they arranged to rent a storefront at 3021 24th Street, between Treat and Harrison, that the church food buying club had been using to warehouse bulk items. There in January, 1973, they opened a co-op/collective store called Semillas de Vida/Seeds of Life.(21) Its stated mission was making inexpensive nutritious food available to the community, not for profit, changing the way food is dealt with from seed to table, and helping to bring about greater social justice and equity. It was to be democratically run by the collective, also using the volunteer labor of the customers. Seeds had several advantages over the Conspiracy. With a storefront and inventory, food buyers no longer needed to pre-order once a week, put up front money, or deal with distribution. A back room of Seeds was quickly taken over by another collective, People’s Bakery, which originally started baking just for the store. Seeds was the first store in the People’s Food System.

Meanwhile, in many regions of the country in the early ‘70s, similar collective businesses were springing up independently in a wide spectrum of small industries and services, not uniquely in the food industry. Collectives became a social movement in their own right, a movement for workplace democracy, with the Bay Area as one of the movement’s centers. These small cooperative businesses were run by non-hierarchical egalitarian worker collectives and based on self-help and mutual aid. The idea was in the air, and anyone could pick it up and run with it. Outside the food industry there was no networking organization among these collectives in the early years, and each enterprise was somewhat an island unto itself.

Organic and natural food was the only industry in which the economic conditions encouraged extensive networking among collective businesses, a vertical and horizontal movement of small inter-connected groups. Not just stores, but farms, distributors, and restaurants could be and were organized by collectives, in many parts of the country. The older Rochdale consumer co-op movement called this latest development the “new wave.”

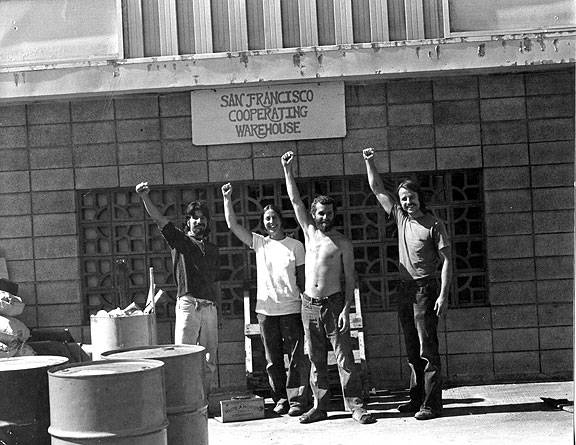

The next San Francisco collective store developed out of the Noe Valley Food Conspiracy. Inspired by Seeds, that neighborhood food club gave birth to the Noe Valley Community Store at 1599 Sanchez in October, 1973. The two stores, Seeds and Noe Valley, were in close touch, and began talking about themselves as the People’s Food System. Both stores needed warehouse space, so they jointly opened the San Francisco Common-Operating Warehouse (SFCW), also sometimes called the Cooperating Warehouse, on Bancroft Street in Hunters Point. The Warehouse quickly became an autonomous collective and a center for the growing movement. It soon moved to a larger warehouse at 155 Barneveld Avenue, in the industrial zone below Bayshore Boulevard.

Workers at the Cooperating Warehouse loading dock, c. 1976.

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

Alice's Restaurant at 1599 Sanchez (corner of 29th Street) occupies the site of the original Noe Valley Community Store.

Photo: Alice's Restaurant

Over the next two years, the collective idea begun at Seeds burgeoned into a growing network of groups scattered around the city. Food System workers staged a communal effort to help key members of the Bernal Heights Food Conspiracy to open Community Corners at 47 Powers in 1974. A group of the most active core members of the Haight-Ashbury Food Conspiracy opened the Haight Community Food Store at 1920 Hayes. Early in 1975 a fifth store, Good Life Groceries opened at 1457 18th Street.

Protestors demonstrate to save Potrero Hill's Good Life Grocery, since relocated to 20th Street from its location in this picture on 18th.

1979 photo courtesy Potrero Hill Archives Project

Meanwhile, support collectives were forming: Veritable Vegetable, Merry Milk, Red Star Cheese, Yerba Buena Spice Collective, and Honey Sandwich Day Care, a child care center for Food System workers. These support collectives were all housed in a warehouse dubbed the Food Factory, at 3030 20th Street, not far from Seeds. People’s Bakery moved in with them. Affiliated was also a distribution collective, People’s Trucking. The three people who started Seeds all moved on to different support collectives, Mark to Red Star, Betty to the Warehouse, and Margie to People’s Bakery. Seeds became mostly run by a collective of Latina women, some of them refugees from the civil wars in Nicaragua and El Salvador.

The "Food Factory" was in this building at the corner of 20th and Alabama Streets in the mid-1970s.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The new stores involved a large increase in property and responsibility over the Food Conspiracy. Some of the workers in the core collectives received wages from the beginning, but at very low rates. The core collective’s job was keeping it together, but on a day-to-day basis, the enterprises were run mostly by volunteers, with decisions made in the same collaborative democratic spirit that shaped the original food conspiracy. Usually anybody could volunteer, and it was extremely easy to become a member of the store collective, since many workers were still waiting to get paid a living wage. This ease of entry was a strength of the early collective stores, but it also became a vulnerability. By every report, the early stores were all a little funky, by middle-class standards. Morris Older, a worker at Uprisings Bakery, later remarked, “All of these stores were capitalized by volunteer labor—as a result, prices could be kept very low. The stores operated on a 15 percent markup (most stores mark-up food from 40 percent to 75 percent above their cost) and so the idea spread very quickly among the nutrition-conscious white countercultural Bay Area community. Yet running the stores meant keeping them stocked and staffed, paying bills and making orders on time, all of which meant that consistent trained labor was at a premium.” (22)

Some people who shopped at the new stores did not have the time or inclination to put in volunteer labor; on the other hand, various individuals put in large amounts of time, primarily from enthusiasm and in belief in the goals. Older observed that “Some had a vision of a people’s food system that would completely bypass the large corporations and supermarkets that now supply the food most Americans eat. Organic farming collectives would grow it, and trucking collectives would bring it to the city to be sold at community food stores.”(23)

But at first, most collective stores could barely pay their workers. The idea was that they were putting in sweat equity, as in any small startup business, that would eventually pay off. The rule of thumb in startups at that time—as today—is to not expect to make a profit for at least the first two years. All the early stores were undercapitalized, and those that survived did so despite all odds. Few collective workers knew standard business practices very well and improvised as they learned. Many groups had no idea how to keep books. They thought of themselves as nonprofit or anti-profit and had endless debates about what those terms meant. Even defining what profit meant was not an easy thing. Some collective members had read a little anarchist literature or Marxist economic theory, and numerous discussions became filled with jargon and concepts that many found confusing, alien, doctrinaire. But even the most committed people could live only so long without income, and most soon came to the point that they could not continue unless they were adequately paid.

There always remained some ambiguity over control of SFCW, the Common- Operating Warehouse. Should it properly be autonomous, or controlled by the stores and support groups that used it? Many issues formed inside that ambiguity. SFCW had a dual identity. The Warehouse started as a community resource, and all felt that they had to support it. All the stores were stakeholders and wanted a fair share of control. At the same time, everyone supported self-management and worker control. The question was between ownership by the community of stores that used the warehouse or by the worker collective that ran the warehouse. That fuzzy concept is sometimes called social ownership, the notion of social property belonging to everyone and at the same time belonging to no specific individuals.

As the volunteer core groups abandoned the Food Conspiracy, the White Panther Party (WPP) started running much of the network. WPP turned what was left of the Conspiracy into a social enterprise with paid workers. At the same time they were also involved with the People’s Food System, and WPP members worked in several PFS enterprises, including the Warehouse and Veritable Vegetable.

Collectives and Legal Structures

From the beginning the question of structure, legal as well as informal structure, was a knotty one for the collectives and cooperatives. Because their primary purposes involved social goals, and not simply a maximization of profits, they did not fit well within the usual categories of capitalist enterprises, or even cooperative law as it existed in California at that time. The collectives were continually reinventing themselves. The participants did not all agree about what they were doing or why they were doing it. The great majority, however, did agree that they were not doing it primarily for profit and had social missions. Today the structures that many of them were struggling toward are usually called social enterprises or solidarity enterprises—nonprofit cooperatives or semi- cooperatives with a social mission—of which there are now many worldwide.

Since the collective structure was a spontaneous revolutionary formation, collectivists did not feel that they had to conform to the standard capitalist structures dictated by our society. The Bay Area at the time was rife with groups formed for numerous purposes that used the collective direct democracy structure. Many of these groups needed no legal structure beyond an unincorporated association. However, the Food System existed where the rubber hits the road: they were businesses. Outlaw businesses perhaps, but businesses: they had to have legal structures.

The Noe Valley Community Store was the first to file incorporation papers with the state, on October 12, 1973, with the founding directors listed as Michael Martin, Carl Fauset, Susanne DiVincenzo, and James Ploss. Their original name was actually the Noe Valley Free Store, and their original purposes were much broader than food. The Free Store refers back to store that the San Francisco Diggers ran in 1967. The structure that Noe chose, and even the words they used to describe their organizational purposes, set the pattern for the entire Food system. They chose the structure of a nonprofit corporation for educational purposes, and not a cooperative corporation, under California law. This is very important in understanding the Food System and many other pioneering social enterprises of the era. The problem of legal structure cropped up at the very beginning of the counterculture in the mid-1960s. The rural communes of that era always had that issue. Somebody had to own the land and property, and if you ran a business, you had to have a legal structure.

In Noe Valley’s incorporation papers, running a food store was not presented as their central focus. They listed their “primary and specific purposes” as “to promote social welfare by conducting an educational program”:

The educational objectives of this program are to teach by participation and by example the following ideas, practices, and techniques:

(1) voluntary commitment of substantial and regular amounts of unpaid labor to the benefit of others and of the community as a whole

(2) self organizing of community groups to solve shared problems as an alternative to reliance on the use of government or private enterprise for that purpose the essential unity of work, community service, and individual and group educational development

(3) direct democracy in the governing of group’s affairs

(4) business and retail sales management skills

(5) nutritional science and economics; particularly with respect to organic natural, unprocessed or fresh foods (24)

They went on to state that they intended to conduct “a publication program, discussion groups, panels, and on-the-job skills training of high turn-over, temporary, unpaid or subsistence-paid staff in a retail food store.”

Almost all the People’s Food System collectives followed Noe Valley’s lead and incorporated as nonprofit educational organizations, using much the same language. The next collectives to incorporate were the Warehouse, Seeds, and Red Star. They all filed on the same day, December 11, 1974. The directors of SFCW were Charlotte Woods, Nina Saltman, and Ellen Helford; of Seeds were David Reardon, James Jackson, and Elizabeth Perry; and of Red Star, Jerry Walker, Maxine Lieberman, and Dahlia Rudavsky.

SFCW and Seeds filed identical papers:

the primary and specific purposes are to promote social welfare by conducting educational programs in the areas of human nutrition and food distribution. The programs will be directed at the public as a whole in subjects beneficial to the community and useful to individuals. The educational objectives of this program are to teach by participation in practical work situations the following ideas, practices, and techniques:

(1) Self-organizing of community groups to solve shared problems as an alternative to reliance on the use of government or private enterprise for that purpose.

(2) Direct democracy in the governing of group’s affairs.

(3) Nutritional science and economics; particularly with respect to organic natural, unprocessed or fresh foods.

(4) Skills necessary for all phases of retail food distribution.(25)

Red Star’s papers contained a few minor differences, but did not mention its primary focus, distributing cheese. The Haight Community Food Store followed, incorporated by Ira Schwartz, Marin McCall, Ruby Newman, and Omar Benoit, copying Noe’s purposes word for word, and adding the development of a childcare-community center. Good Life Groceries used the same typical structure, although its core was really not a collective group but a couple, Lester Zeidman and Kayren Hidiburgh.

Shortly before incorporating, Veritable Vegetable, the produce distribution collective, wrote an expansive description of their purposes in Turnover, the Food System newsletter:

a) supply high-quality, low-cost produce to non-profit community cooperating food distributors (stores, clubs, etc.)

b) buy produce from small growers; buy organic produce whenever possible.

c) Veritable Vegetables strives to be a non-hierarchical collective workplace where all decisions are made by the workers. We are non-profit, by which we mean that all net profits after wages, rent, capitalization, depreciation, liabilities (debts), taxes, and other costs do not go into the pocket of any one person but are put back into the business or the community.(26)

However Veritable Vegetable, unlike the others, incorporated as a for- profit corporation, with a total of 500 shares, all of one class, with the par value of $10.00 per share. Stock was non-transferable “except as approved by a unanimous vote of the board of directors.” Their purposes were described in their incorporation papers as:

(a) To engage primarily in the specific business of purchase and distribution of produce to the stores in the group commonly known as the San Francisco Co- operating food system and its affiliates; (b) To engage generally in the business of education as to the values of collective effort, worker control of workplace, direct marketing, and minimal use of petrochemicals in the production and preparation of food.(27)

Veritable Vegetable’s first board consisted of Richard Comberg, Stuart Fishman, Shirley Freitas, Margaret Janosh, Mary Masterson, and Janet Ploss. According to Mary Jane Evans, “Stuart was the main force behind Veritable. He had very well thought out the reason why he was there. He was compelled by the whole structure of agriculture in California. He was also involved with a work structure that had to do with collective participation. The emerging idea of sustainability and organics in agriculture.”(28)

While Veritable wanted the stores to buy produce exclusively from them, because they needed the volume to make their business work, some collectives continued to buy part of their produce directly from the produce market. This created an ongoing conflict that eventually focused into a polarization between Veritable and Ma Revolution.

Notes

19. Minnesota Historical Society, “North Country Co-op: History.”

20. Craig Cox, Storefront Revolution, Food Co-ops and the Counterculture, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994), 40-41.

21. Morris Older, “The Peoples Food System,” in History of Collectivity in the San Francisco Bay Area, ed. John Curl, (Berkeley: Homeward Press, 1982), 38-39; “The Rise and Demise of the Peoples Food System,” Grassroots, Berkeley, July 1, 1981, 6-7. The role of Father Hagan is from an email from Adam Raskin to John Curl, November 8, 2011.

22. Older, “Peoples Food System,” 39.

23. Ibid.

24. “Articles of Incorporation of Noe Valley Free Store, Inc.”, filed October 12, 1973.

25. “Articles of Incorporation of San Francisco Common-Operating Warehouse, Inc.,” filed December 11, 1974; “Articles of Incorporation of Semillas de Vida, Inc.” filed December 11, 1974.

26. “Veritable Vegetable,” Turnover 10, March, 1976, 15.

27. “Articles of Incorporation of Veritable Vegetable, Inc.,” filed June 14, 1976.

28. Interview with Mary Jane Evans, recorded July 25, 2011.