THE FINANCIAL DISTRICT

Historical Essay

by Richard Walker, 1998

Aerial view from south to north, San Francisco's Financial District and environs, 1953.

Photo: Ed Brady

Downtown Expansion: Property and Progress

From the Depression through the fifties, decaying urban cores were a national obsession. San Francisco business leaders in particular suffered from intense vertigo induced by a metropolis spinning outward like a red giant, threatening to leave a dwarf city behind. This spurred coordinated action through bodies such as the Public Utilities Commission, the Regional Plan Association and the Bay Area Council. A plan for a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system was drawn up by Bechtel Corporation to keep commuters flowing downtown. This was conceived in 1942 and built in the 1960s. The 1940s also saw the first designs for a freeway network, spurred by national planning for a national defense highway system. The California Department of Highways went to work right after the war, and freeway madness hit full speed with passage of the 1956 Federal Highway Act. Freeways were soon marching up from the Peninsula, around the waterfront, and behind the Civic Center. Freeway off-ramps led directly into all the principal redevelopment zones. New bridges were envisioned across the northern and central bay. Obsolete forms of transit, like cable cars and trolleys, were destined for the scrap heap.

Urban renewal legislation passed by Congress in 1949 and 1954 gave cities the power to assemble land, clear it of offending uses, and finance redevelopment. San Francisco, like all big cities, established a Redevelopment Agency to spearhead its efforts. Justin Herman directed that agency aggressively for many years, backed by the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association (a citizens group), and later the Convention and Visitors Bureau (arm of the hotel and tourism industry).

The first renewal plan targeted the Western Addition, an area of dense rental housing occupied by former wartime shipyard workers, many of them black. The Agency aimed to rid the city of over two square miles of Victorian houses, replacing them with thirty-three ten-story slabs to lure middle-class suburbanites back to the city. One planner put it succinctly: “Nothing short of a clean sweep and a new start can make the district a genuinely good place in which to live.” The project began by ramming through the Geary Expressway and clearing old Japantown for a retail complex; then it headed south on both sides of Fillmore. Four thousand people were rousted out in the late 1950s and over 13,000 in the 1960s. Over 1,000 Victorian houses were clear cut, eliminating ten percent of the city’s total stock.

Along the northern edge of Downtown lay the produce district, eyed for renewal. The Blythe-Zellerbach Committee, formed in 1956, drew up the Golden Gateway project (including the Embarcadero Center, to be built with Rockefeller and Mellon money). The Montgomery Block, the city’s oldest building and bohemian haunt, was cleared in 1959. Cyril Magnin, port commissioner and later president of the Chamber of Commerce, had the city buy back its port from the state in 1959, then offered a grand design for hotels and offices along the Embarcadero. Chinatown was targeted and Portsmouth Square was torn up for a parking garage. Manilatown, a stretch of Kearny Street known for its many Filipino residents and shops, was slated for demolition.

South of Market an assault was planned on Skid Row. In 1954, Ben Swig, the biggest hotel owner in San Francisco, laid out a nine-block Yerba Buena project as a combination convention center, stadium, hotel, and park. The area was a jumble of single-room-occupancy hotels built after 1906, replete with eateries and entertainments for the poor; occupants were overwhelmingly single, retired white men, blacks, and Filipinos who had worked as dockers, sailors, and day laborers. For years, San Francisco had the highest proportion of hotel housing of any city in the United States.

Urban renewal was only the prelude to the property boom that followed from 1960 to the recession of 1973–1975. The planners need not have worried, after all. Soon Downtown was bristling with new skyscrapers. Any number of buildings could be cited as flash points for opposition to Manhattanization: Bank of America’s Darth Vader hat, Transamerica’s pyramid, new hotels around Union Square, or a proposed US Steel tower flanking the Ferry Building. After 1975 a new boom came clad in postmodern finishes and Downtown surged across Market Street until halted by the recession of 1985–1986. Twenty-five-million square feet of new office space were added, doubling the size of the corporate heart of San Francisco. More hotels went up, and dozens of cheap residential hotels in the Tenderloin were converted for upscale uses.

The tragedy is not that Downtown grew and San Francisco was physically transformed; rather, it is the way in which thousands of ordinary people and urban places the size of a small city were cleared away with the rubble. In the symbolic contest for space, the victims shrink to insignificance. The class and race hatred behind the Downtown master vision should not be underestimated. The ruling elite sought to level the waterfront haunts of longshoremen who had brought the city to its knees in 1934, to drive blacks out of the Fillmore, to sweep aside the aging and discarded workers from their last redoubts south of Market Street, and to be rid of eyesores such as Manilatown. Crowds, dense quarters, and the commingling of classes and races have always provoked a chill of horror in the heart of the local bourgeoisie.

View of downtown from the bay

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Downtown Encircled: Resistance on Many Fronts

As soon as the grand design for Downtown was put into motion, San Francisco was shaken by popular revolt. The first volleys were fired from the northern flanks of Telegraph and Russian Hills by well-to-do (but often bohemian) residents worried about their bay views. Friedel Klussman put her foot down over the removal of the cable cars as early as 1947, winning them National Landmark Status in 1964. Then came the Freeway Revolt in 1956, triggered by the advancing Western Freeway that was to run through Golden Gate Park. The Supervisors stood up to the state highway department in 1959, and San Francisco became the first city to stop the freeway mania. Next, apartment buildings on the northern waterfront were killed by shipping magnate William Matson Roth and his friends, and Ghiradelli’s shuttered chocolate factory was resurrected as a cozy shopping plaza, becoming the model for such conversions around the world.

Organized under the Western Addition Community Organization and several African American churches, the people of the Fillmore fought against the bulldozers and for replacement housing. They won the first court injunction in the country against an urban renewal project in 1968, and local Congressman Philip Burton pushed through a law requiring compensatory housing. After that the southern tier of the clearance area was filled with public and subsidized housing for the poor. The African American neighborhood was not eliminated, and it eventually reoccupied a large part of the redeveloped housing (but the wretchedness of the ghetto dwellers also produced the People’s Temple and its mass execution at the hand of Jim Jones). The project was a dismal failure in attracting investment, and huge swathes of land lay barren for twenty years.

The historic preservation movement was born of this rebellion. A taste for Victorian houses was produced not so much by revulsion at modernist aesthetics as from distaste for the modern wrecking ball. A City Landmarks Commission was established in 1968 and the Foundation for San Francisco’s Architectural Heritage in 1971. Political alliances made for strange bedfellows, with the Junior League of San Francisco working hand in hand with African American groups, gay activists, and gentrifiers. As a consequence, the political significance of architectural preservation in San Francisco was more radical than the commercial heritage industry that swept the country in the 1980s.

Meanwhile, as the familiar skyline disappeared behind an archipelago of towers, the high-rise revolt erupted. Enter Alvin Duskin, who had fought off Lamarr Hunt’s mad scheme to place a giant Apollo spacecraft on Alcatraz. Duskin wanted a drastic height limit on buildings, and his ballot initiatives of 1971 and 1972 gathered support from a broad coalition of preservationists, hillside dwellers, environmentalists, anti-redevelopment groups, and political progressives. Though defeated, they spurred city officials, led by Planning Director Allan Jacobs, to write a new Downtown plan, with a line drawn at Kearny and Clay Streets to stop Downtown’s northward and westward march. This was too late to save the International Hotel, bought for a high-rise by Hong Kong investors but defended from the wrecking ball by thousands of angry demonstrators, before finally being torn down in 1978.

An elderly cohort of workers in the South of Market, living out their days on meager pensions and vilified as winos, were similarly being forced out by the Redevelopment Agency. But the old men drew on their experience in organized labor, forming the opposition group Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment, under George Woolf, former president of the Alaska Cannery Workers Union, and Peter Mendelsohn, former seaman and Communist Party organizer. By a series of lawsuits, they were able to extract new housing projects for the poor and elderly. Protracted opposition led to the collapse of the project by 1975, to be replaced by a stripped-down version. Ground was broken for a convention center in 1979, yet two huge city blocks lay barren for another decade.

Discontent with the rule of Downtown and with the transformation of San Francisco also surfaced in residential neighborhoods such as the Haight, the Castro, and Noe Valley. Activists began pushing an electoral reform plan that pivoted on district elections of the Board of Supervisors, picking up the support of gays, hippies, African Americans, Asians, and the progressive white middle class. The key figure in the revolt of the neighborhoods was Harvey Milk, the man most responsible for turning the Gay Awakening into a political movement. The return of district elections allowed Milk to take a seat on the Board of Supervisors in 1977 as the country’s first openly homosexual elected official.

Electoral reform mobilization converged with the efforts of the anti-high-rise and anti-renewal forces to unseat Mayor Joe Alioto, leader of the pro-growth coalition. They also dovetailed with the political aspirations of George Moscone and the liberal Democratic machine of Phil Burton. The building boom went bust between 1973 and 1975, throwing the developers into disarray and giving opposition forces a precious opening. Moscone beat out John Barbagelata for mayor in 1975, on a promise to return control to the neighborhoods and end high-rise construction. Moscone did not keep his promise, though he did appoint some valuable mavericks, such as Sue Bierman, to the Planning and Landmarks Commissions. Neither Moscone nor Milk was allowed to finish his work. Both were assassinated in 1978 by Supervisor Dan White, a reactionary ex-cop and Marine, who represented a white working class suspicious of a changing civic landscape and the lone remaining spokesman for Downtown interests on the Board.

In the Tenderloin another grassroots mobilization took shape in the early eighties, led by Brad Paul of the North of Market Planning Coalition, Cecil Williams of Glide Memorial Church, and Leroy Looper of the Cadillac Hotel. Encroachment from Union Square, building conversions, and rising rents were forcing out the elderly residents. But opponents were able to win rent and conversion controls that held the property owners at bay, while nonprofits and churches began upgrading buildings for the poor.

As the property market heated up again, anti-high-rise activists forced votes on height limits in 1979 and 1983. These initiatives narrowly lost, but officials were again forced to respond, with Planning Director Dean Macris’s Downtown Plan. This new plan altered very little, holding the line in the Financial District (where property values and landmarked buildings prevented most building anyway) and giving its blessing to construction south of Market. Activists responded with Proposition M, a more severe containment measure, which finally triumphed in 1986. The battle over Downtown catapulted liberal Art Agnos, another Burton prodigy, into the Mayor’s office, but he promptly lost supporters by backing unsuccessful ballot issues for a new baseball park and an end run around Prop M by the gigantic Mission Bay project. The building boom was exhausted all the same, terminated by economic crisis.

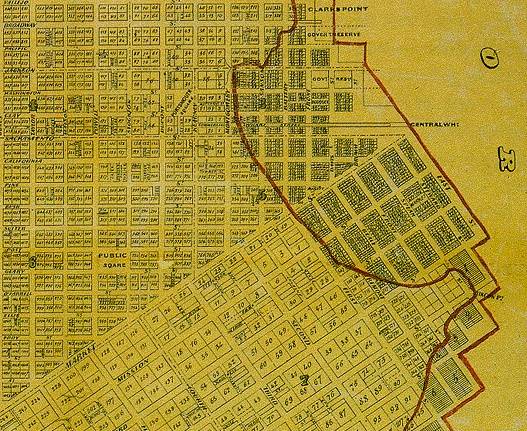

This copy of the Burnham map shows the outline of the original bay in red. Burnham attempted to unify the two different grids the city is laid out in.

Map: Bancroft Library, Berkeley, CA

This article is excerpted from "Appetite for the City," published originally in Reclaiming San Francisco: History Politics Culture, a City Lights anthology edited by James Brook, Chris Carlsson, & Nancy J. Peters (City Lights Books, San Francisco: 1998)