The Day the Biggest Mechanical Toy Stopped

Historical Essay

by Mae Silver

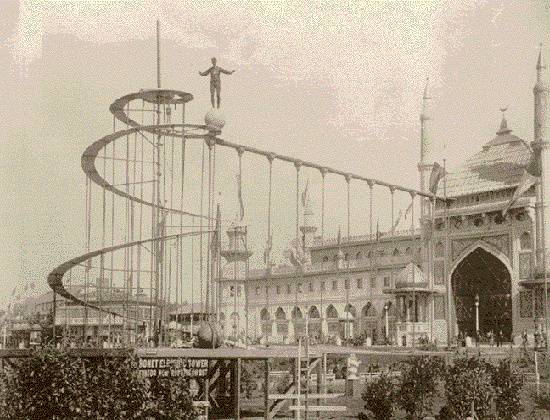

Midwinter Fair 1894, Golden Gate Park. Achille Philion, the Marvelous Equilibrist, in his Spiral Tower Revolving Globe Exhibition.

Photo: Taber

By one measure, the Midwinter Fair succeeded in displaying the most ingenious machines that had been invented up to that year of 1894. The vertical merry-go-round, named after its owner in Chicago the Ferris Wheel, and after its owner in San Francisco the Firth Wheel, was a stellar success at both fairs. The revolving wheel was the perfect toy to convince fair-goers of all ages that machines were not only user-friendly but they were fun! At night, thousands of light bulbs, the latest electrical superstars, transformed the fairgrounds into a brilliant fairyland. Mr. and Mrs. America bought the concept that electricity and machines would make their future as bright as the fair at night. Did any of them have second thoughts?

Outside of the Midwinter Fair, the depressed economy and joblessness prevailed and sometimes raged so violently the troops were summoned. The Fair Commissioners had a fine and tricky line to gauge between the ongoing party called the Fair and the desperate suffering the unemployed people of this country and city endured.

It was Mr. Pullman who lit the fire that led to bloodshed and explosions in Chicago in the summer of 1894. Mr. Pullman, of Pullman railroad car fame, declared a reduction of wages of his employees. Aiming to be cost effective in the depression, he lessened his overhead that way. However, Pullman did not take into account the other logical step his employees anticipated. In the town called Pullman which he owned, many of his employees rented houses and bought items at the various service centers. His workers expected Mr. Pullman to reduce their rent and fees in Pullman. He did nothing of the kind. When they approached him with this request, he dismissed the idea. Pullman's employees were devastated and became angry. They decided to boycott handling any more Pullman cars.

Behind the scenes, Eugene V. Debs, leader of the American Railway Union, tried to get Pullman to arbitration. He refused. With that cold towel in the face treatment, the ARU voted to boycott Pullman cars. Soon every Pullman car in Chicago was idle. The response went national. The boycott became a strike that shut down the nation's biggest mechanical toy-the railroad. Pullman answered with an appeal to the Federal government and secured a Federal injunction to suppress the strike. Imitating Pullman, Debs ignored the injunction.

On July 7, 1894, Federal and state troops entered Chicago to put down the thousands raging in the railroad yards and city streets. Chicago's railroad yards became the front line of a battle between rioting railroad workers and the army. Many lives were lost. Railroad tracks, previously the scene of high level of business energy, became awash in blood and littered with bodies. Illinois Governor Altgeld, a populist, appropriately outraged by the presence of troops in his state, protested to Washington that Federal intervention was "unconstitutional." The matter went to the Supreme Court which ruled the strike illegal. That court decision killed the American Railway Union. While the Court discharged its duty, the working people across the country remained raw, indignant and hurt.

President Grover Cleveland appointed a Federal commission to investigate the causes of the Pullman strike. More than one hundred railroad officials, labor leaders, strikers, and public servants testified before the commission. It concluded the responsibility of the boycott rested with the people and their government that did not adequately regulate monopolies and did not protect the rights of the workers. Suddenly, it seemed, for that one moment, there was a new wind gathering in Washington. A new order with a social conscience stepped forward to support the American working people.

The national railroad strike, of course, affected transportation to San Francisco and diminished the attendance to the Midwinter Fair. The San Francisco Examiner had a popularity contest to determine which county exhibit was the best, second, and third. Since opening day, fairgoers had voted by ballot. On July 6, 1894, the winners were announced. Solano County delegates who won the prestigious Gold Cup, arrived to claim their prize. So did Sacramento County which won the third prize loving cup. But Alameda County representatives, unable to travel because of the Pullman strike, were not in San Francisco to receive their beautiful silver punch bowl— "...not a car moved out of Oakland."

—Mae Silver

Sources:

Gilbert, James Perfect Cities Chicago, 1991

Meltzer, Milton Bread and Roses NY, 1967

San Francisco Examiner June 30; July 5,6,7, 1894

Read More on the Midwinter Fair on Foundsf:

’49 Mining Camp glorifies Gold Rush Fantasies