The Freeway Revolt

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/hidden-san-francisco-stop-t-11-freeway-revolt" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

![]()

Next Stop #6: UFW v. DDT

Freeway protesters in City Hall, 1966

Photo: San Francisco Chronicle

| Beginning in the late 1950s until 1966, the city of San Francisco underwent a polarizing internal debate over a series of proposed alterations to its transportation infrastructure. This off-and-on informal conflict of ideas, nicknamed the “Freeway Revolt,” pitted a variety of political, mercantile, and ideological interests against each other with the future of the city's neighborhoods and livability at stake. Tracking the revolt’s chronological progression while also relating it to a larger historical context and the emphasis on mass transit that resulted, the article moves into the 21st century to show the shift in urban planning priorities. |

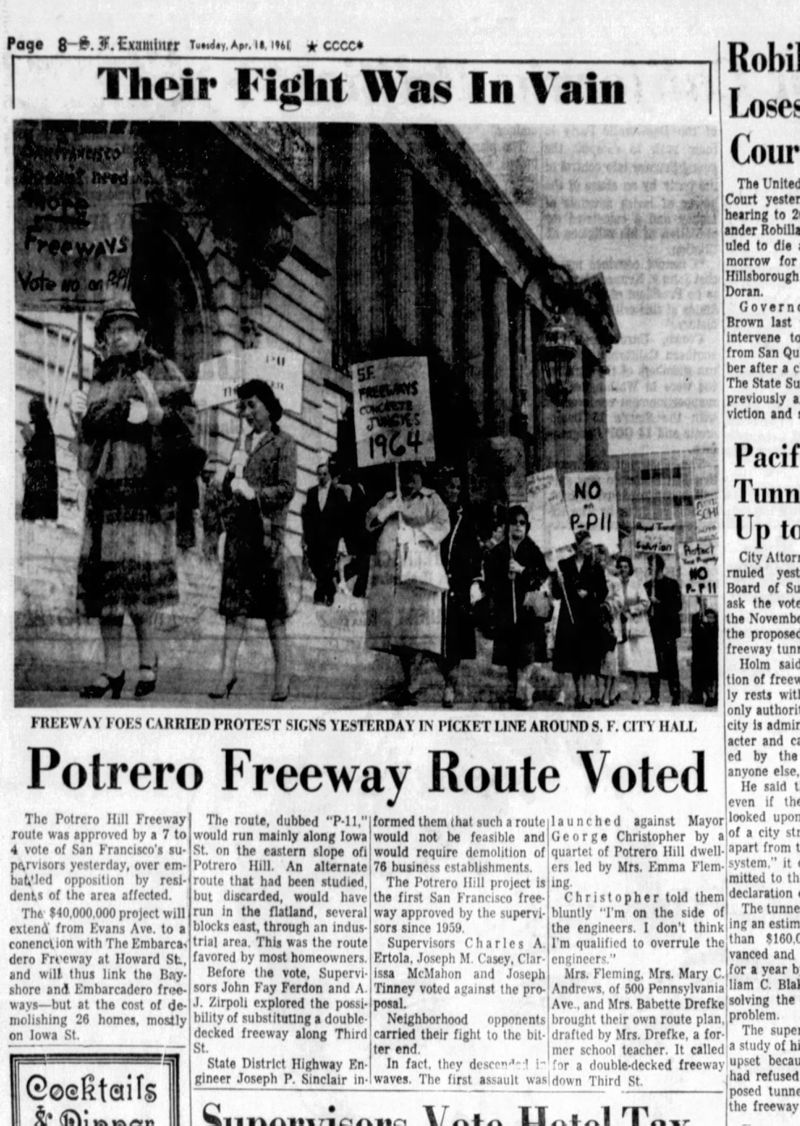

Picketers protesting against the I-280 Freeway route cutting off the east side of Potrero Hill marching at City Hall, April 18, 1961.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Front page SF Examiner coverage of failed protest against I-280 route.

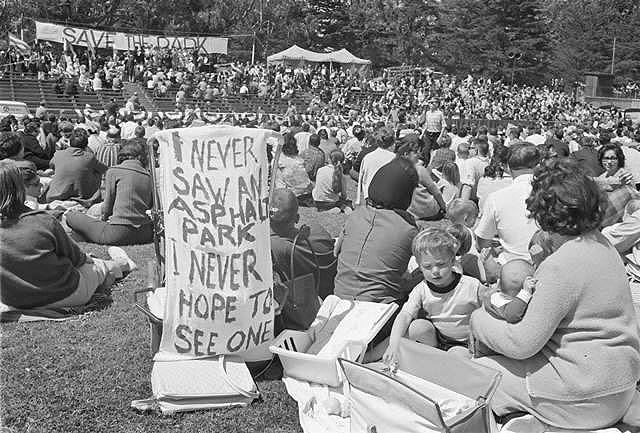

Save the Panhandle Park rally in Golden Gate Park, May 17, 1964.

Photo: Bancroft Library

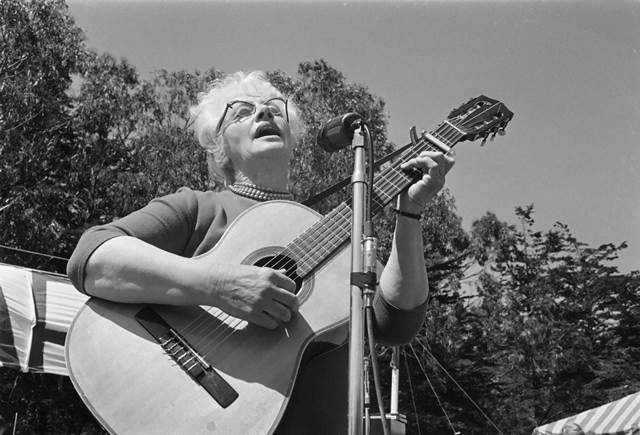

Malvina Reynolds sings her anti-freeway ballad at the May 17, 1964 rally to save the Panhandle in Golden Gate Park.

Photo: Bancroft Library

<iframe width="560" height="105" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/dKqZmYE-yI8?rel=0" frameborder="0" gesture="media" allow="encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Malvina Reynolds singing "Cement Octopus," her anti-freeway anthem from 1964 (lyrics below).

- There's a cement octopus sits in Sacramento, I think.

- Gets red tape to eat, gasoline taxes to drink.

- And it grows by day and it grows by night,

- And it rolls over ev'rything in sight.

- Oh, stand by me and protect that tree

- From the freeway misery.

- There's a cement octopus sits in Sacramento, I think.

- Who knows how the monster started to grow that way,

- Its parents are frightened, they wish it would go away,

- But the taxes keep coming, they have to be spent

- On the big bulldozers and tanks of cement,

- Oh, stand by me and protect that tree

- From the freeway misery.

- Who knows how the monster started to grow that way,

- That octopus grows like a science-fiction blight,

- The Bay and the Ferry Building are out of sight,

- The trees that stood for a thousand years,

- We watch them falling through our tears,

- Oh, stand by me and protect that tree

- From the freeway misery.

- That octopus grows like a science-fiction blight,

- Old John MacLaren won't take this lying down,

- We can hear his spirit move in the sandy ground,

- He built this Eden on the duney plain,

- Now they're making it a concrete desert again,

- Oh, stand by me and protect that tree

- From the freeway misery.

- Old John MacLaren won't take this lying down,

- The men on the highways need those jobs, we know,

- Let's put them to work planting new trees to grow,

- Building new parks where kids can play,

- Pushing that cement monster away,

- Oh, stand by me and protect that tree

- From the freeway misery.

- The men on the highways need those jobs, we know,

Malvina Reynolds serenading protesters defending the Panhandle from freeway plans in 1966.

Photo: courtesy Saul Heller

Malvina Reynolds in the Panhandle, 1966.

Photo: courtesy Saul Heller

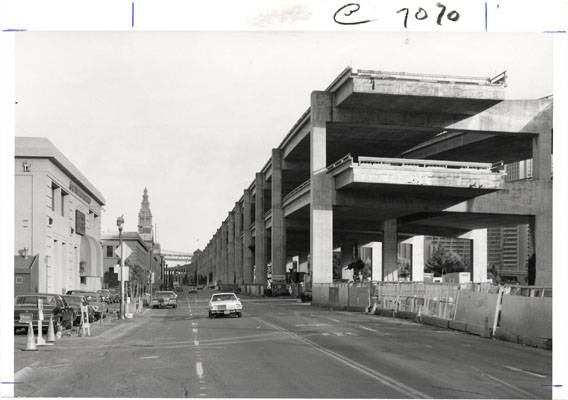

New ramps to Washington and Clay Streets from the Embarcadero Freeway, August 15, 1965.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P14851)

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/EmbarcaderoFreewayEntry1957" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

1957 entry to the Embarcadero Freeway, before it was finished, a harrowing ride!

Video: courtesy Prelinger Archives, Lost Landscapes of San Francisco

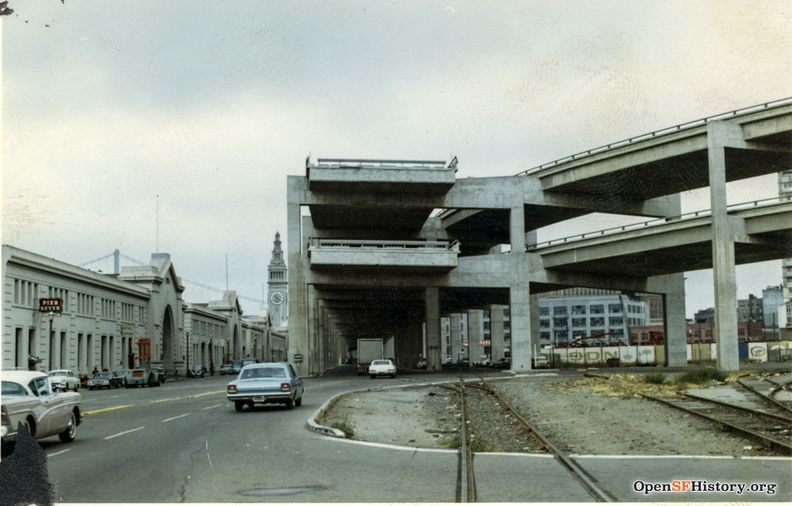

Construction of the Embarcadero Freeway stopped here at Broadway due to popular anger.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Freeway protestors walk along Embarcadero, old Embarcadero Freeway and Ferry Building in background, c. 1964

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

c. 1965, at the Broadway end of the Embarcadero Freeway.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.6035

In the 1950s, the California Division of Highways had a plan to extend freeways across San Francisco. At that time the freeway reigned supreme in California, but San Francisco harbored the seeds of an incipient revolt which ultimately saved several neighborhoods from the wrecking ball and also put up the first serious opposition to the post-WWII consensus on automobiles, freeways, and suburbanization.

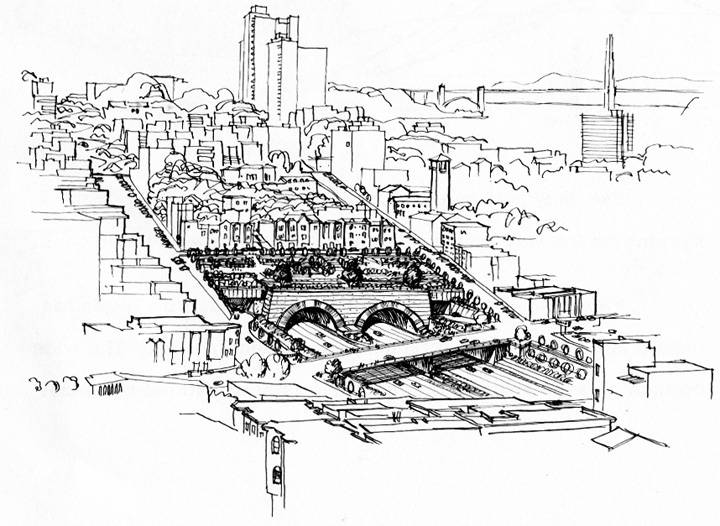

Early plan for 8-lane freeway to cut under Russian Hill on its way from the Embarcadero to the Golden Gate Bridge

The Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Council (HANC), one of the city's oldest and most persistent neighborhood groups, dates its origins to the initial struggles against the proposed Panhandle-Golden Gate Park freeway, which was to extend the central freeway up the Oak/Fell corridor, slice 60% of the Panhandle for the roadway, and tunnel under the north edge of Golden Gate Park before turning onto today's Park Presidio towards the Golden Gate Bridge.

On November 2, 1956 the San Francisco Chronicle graciously published a map of the proposed and actual freeway routes through San Francisco even though its accompanying editorial was already chastising protestors: "The remarkable aspect of these protests and claims of injury is their tardiness. They concern projects that have for years been set forth in master plans, surveys and expensive traffic studies. They have been ignored or overlooked by citizens and public official alike—until the time was at hand for concrete pouring and when revision had become either impossible or extremely costly. The evidence indicates that the citizenry never did know or had forgotten what freeways the planners had in mind for them."

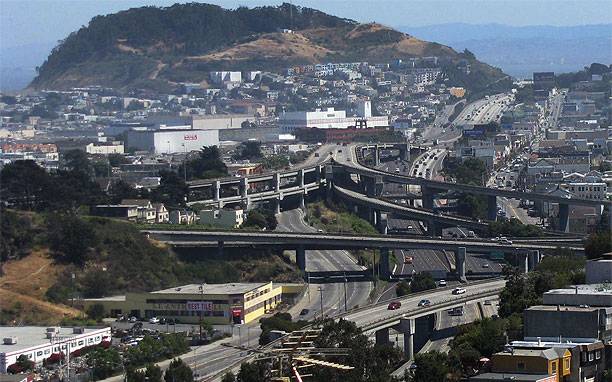

Highway 101 just south of Cesar Chavez exit, 2007

Photo: Chris Carlsson

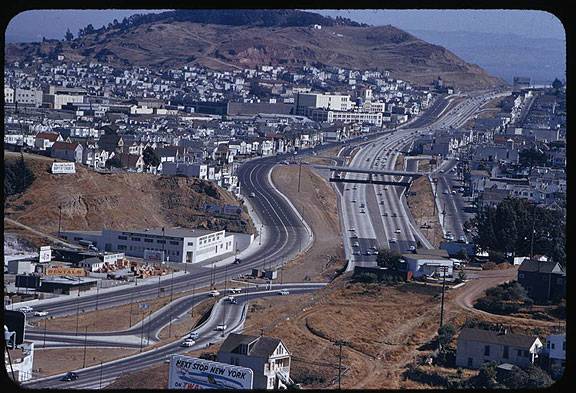

James Lick Freeway under construction in 1953: San Francisco's first. Seals Stadium, the old ballpark is visible in center-left of photo

Photo: Ed Brady

Just three years earlier San Francisco had opened what became known as "hospital curve" both for its location behind General Hospital and its high rate of accidents. On October 1, 1953 the Bayshore Freeway opened from Army to Bryant/7th Street, nearing a later direct link with the Bay Bridge. San Franciscans could now drive three unmolested miles of "divided no-stop freeways" from Alemany to Bryant. The new Bayshore Freeway was the first highway to open after the failed effort of state highway authorities to build a 2nd Bay Bridge right next to the first, a plan they pursued from 1945-49 before it was finally defeated, in part thanks to Mayor Elmer Robinson appealing to military authorities to halt it because it would reinforce the bottleneck the Bay Bridge already presented for getting in or out of the City.

California passed the Collier-Burns Act in 1947, which allowed the construction of freeways to proceed without charging tolls. The Act reoriented the state highway system from multipurpose rural roads to limited-access superhighways and extended them into the cities for the first time. The assumption, which was borne out by developments, is that by building the new highways into the cities, the state gas tax revenues (which were raised 50% in the same bill) would rise rapidly because of all the additional driving the highways promoted among urban dwellers. As it turns out, it was California’s lead that shaped the 1956 Interstate Highway System, which followed the same funding formula. As Katherine M. Johnson has written, the “major flaw of this solution to the rural bias of American highway[s] was precisely its fiscal logic.” Focusing on solving a funding problem ignored basic issues of design standards and integration into the urban fabric. Instead, new highways were marketed as solutions for urban blight, dovetailing with the massive urban renewal programs that were gutting central city neighborhoods in dozens of cities from the late 1950s into the 1970s.

As the plans unfolded, public opposition grew. By the time the Embarcadero Freeway was nearly under construction in 1958, a loud opposition had formed, going on to campaign for its removal after its completion. Over 30,000 people signed petitions at meetings organized in the Sunset, Telegraph and Russian Hills, Potrero, Polk Gulch and other threatened areas. In 1959 The Supervisors voted to cancel 75% of planned freeway routes through the city, much to the shock of the Department of Highways and the state government. But that was not the end of the freeway revolt.

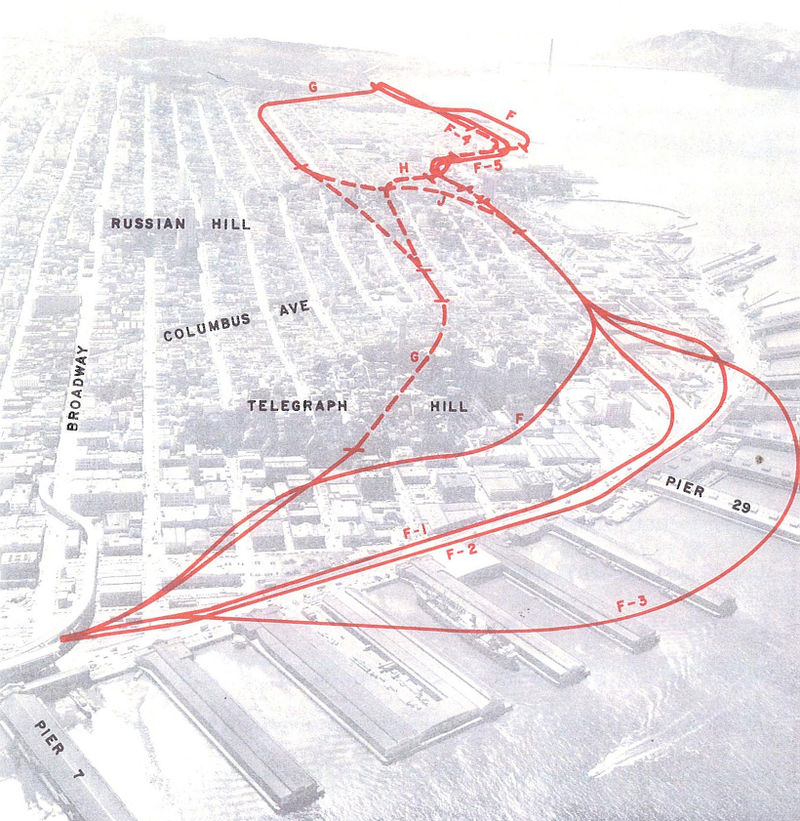

Proposed freeway routes to complete Embarcadero Freeway to Golden Gate Bridge.

Freeway builders continued to resurrect various routes, encountering persistent, well-organized resistance by San Francisco neighborhoods, especially in the Sunset and Richmond where neighbors were dedicated to stopping the proposed Western Freeway. Supervisor William Blake was a key opponent of the freeway planners.

Lost in the story of the Freeway Revolt is the role it played in helping BART get institutional support. After the 1959 Supervisorial defeat of freeway plans, BART advocates got surplus Bay Bridge tolls allocated to the proposed transbay tube. After the 1961 vote against the Western Freeway, Mayor George Christopher and the influential Bay Area Council both endorsed the proposed BART system. As freeway proponents continued to advocate for their plans, Supervisor Blake proposed burying a freeway in a “crosstown” tunnel as an alternative to the “beautified” Panhandle freeway. But state highway officials derided it as an unrealistic and costly plan, and after a year of study, ruled it out. San Francisco officials, including new Mayor Jack Shelley, made it clear they wanted the Embarcadero Freeway taken down and replaced with an underground route, the proposed Golden Gate Freeway, that would connect to the Golden Gate Bridge.

In 1964 the Panhandle-Golden Gate Freeway plan reached a climax, with a May 17 rally at the Polo Grounds to save the Park, featuring a "Natural Anthem" and a dedicated tune by Malvina Reynolds, the famous left-wing folk singer, and a speech by poet Kenneth Rexroth. Months later, in a final, climactic 6-5 vote, the Board of Supervisors rejected the Park Freeway on October 13. Black supervisor Terry Francois cast the deciding vote, delivering a point-by-point six-page rebuttal to the pro-freeway arguments. (It is interesting to note that the other No-votes on that Board were future mayor George Moscone, future CAO/auto dealer and consumer of sexual services Roger Boas, future Lt. Governor Leo McCarthy, William Blake and Clarissa McMahon. In favor of the freeway were "progressive" supervisors Jack Morrison, Joseph Casey, Jack Ertola, Joseph Tinney and Peter Tamaras.) Mayor Jack Shelley was all for it, as was the Labor Council from which he hailed. The Supervisors' Transportation Committee had received a petition with 15,000 signatures, 20,000 letters and telegrams, and had received opposition from 77 community organizations.

After all that, it seemed to be decided. But it wasn’t. More bureaucratic studies and fears of losing several hundred million in federal financing for the City’s highways led to another climax. In 1966, the Panhandle and Golden Gate Freeways were once again brought forward, pissing off the thousands of people who thought they’d already stopped the plans. Ultimatums from the State Highway Commission and much bluster from pro-freeway politicians failed to carry the day. Mobilized citizens and their community organizations won over organized labor, who now opposed the plans too, arguing that jobs would actually be lost if the city became “one long strip of concrete for commuters with bigger and better ghettoes.” Finally, on March 21, 1966 both the Panhandle and Golden Gate freeways were defeated 6-5 by Supervisorial votes.

New Bayshore Freeway soon after opening, April 7, 1955. View from Bernal Heights southeast, with Bayview Hill in background.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P08309)

View southeast from Bernal Heights towards Bayview Hill, 2009.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Today, San Francisco's freeways have changed again, thanks to the Loma Prieta 1989 earthquake. The much maligned Embarcadero Freeway has been removed, as has an unsightly spur of the Central Freeway. A raging debate over the future of the Central Freeway ramps that go north across Market was finally resolved and has now been replaced by the surface Octavia Boulevard. The 101-280 interchange was a mess from 1989 to 1996. New offramps were added to I-280 to serve a new waterfront roadway and the planned Giants ballpark at China Basin in 1997, but no new freeways will be built in San Francisco. New transit money goes to BART and MUNI, while Caltrans and SF Dept. of Public Works continue to spend vast quantities of social wealth on maintaining the San Francisco road system. The rapid rise in value in both areas where freeways were removed, along the now open waterfront, as well as the rapidly gentrifying Hayes Valley/Civic Center area, show that profits can be drawn from forward looking urban planning, de-emphasizing cars and re-emphasizing neighborhood, community, and nature. But most U.S. urban planners still adhere religiously to the cult of the car, hence constant efforts to expand roads and parking at the expense of numerous more sensible alternatives, from decent mass transit to ubiquitous bikeways.

More on the freeways that were planned, some built, most not

For a deeply detailed account of the 1956-66 freeway revolt, see Katherine M. Johnson’s article “Captain Blake versus the Highwaymen: Or, How San Francisco Won the Freeway Revolt” in Journal of Planning History 2009; 8; 56, originally published online Nov. 28, 2008.

See also, William Issel's excellent article "Land Values, Human Values, and the Preservation of the City's Treasured Appearance: Environmentalism, Politics, and the San Francisco Freeway Revolt" in Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 4 (1999).

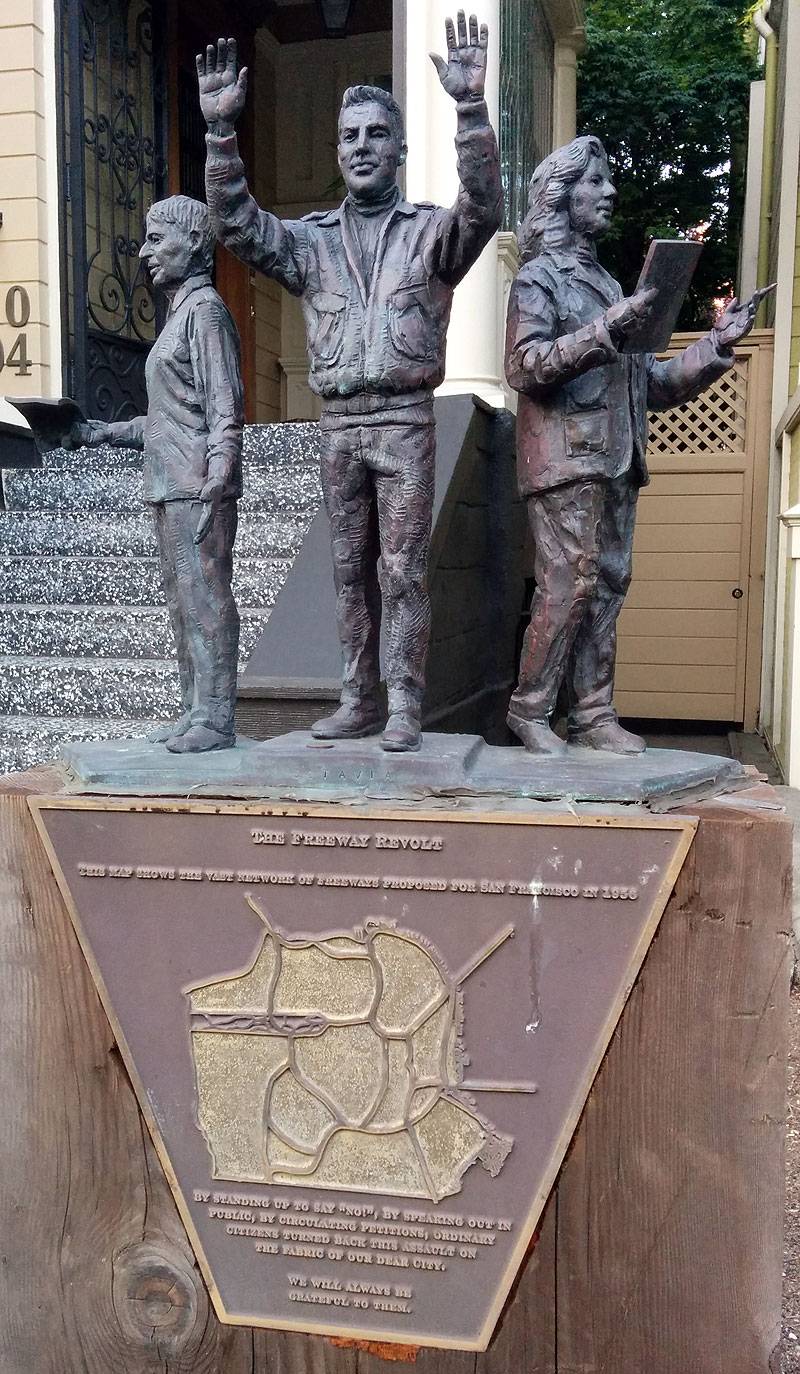

Scale model of a statue dedicated to the citizens' freeway revolt of 1956-65, installed in front of a private home on Gough across from Lafayette Park.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

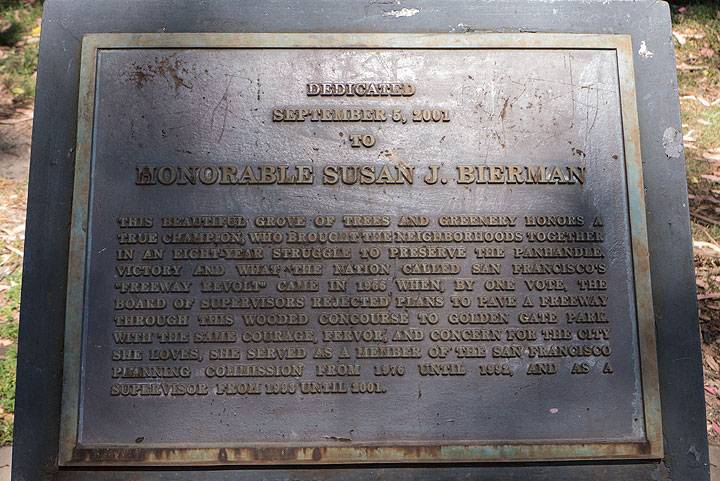

In this circular plaza at the western end of the Panhandle, near Shrader, sits a memorial to Sue Bierman for her role in the Freeway Revolt. She is also honored by having her name on the park where the Washington and Clay Street ramps to the Embarcadero Freeway once sat.

Photos: Chris Carlsson