The Origins of Bay Area Transportation, or Do You Know the Way to San Jose?

Historical Essay

by Robert F. Oaks

originally published in The Argonaut Vol. 14, No. 1

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 and the subsequent “rush” of people to California from all over the world mocked the attempts of state and local governments to provide anything approaching an adequate infrastructure, even when they tried. There were 100,000 or more people in California by the end of 1849, overwhelming the institutions and facilities that had served the previous remote Mexican province.

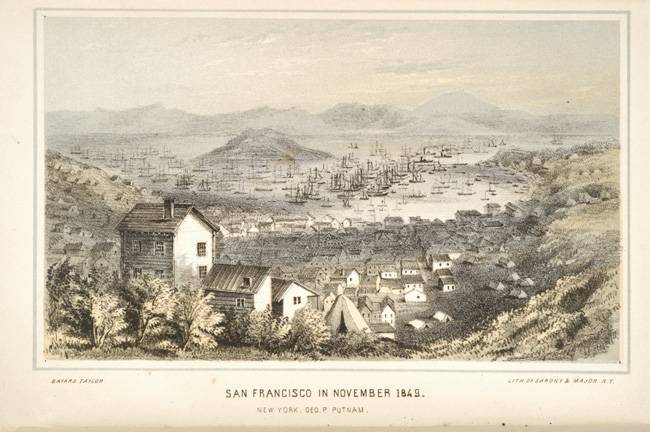

San Francisco, 1849

The sleepy Mexican settlement of Yerba Buena, renamed San Francisco in 1847, became the largest town in California. “The city,” which had only about 1,000 inhabitants in 1848, had upwards of 36,000 by 1852, the date of the first surviving census.(1) The rapid population growth soon made apparent many civic deficiencies, not the least of which were poor streets and lack of adequate transportation, both within the city and to other settlements.

While horses and ox carts had been sufficient in sparsely populated Mexican California, these forms of transportation were woefully inadequate for getting supplies to the gold fields. Water transportation on the Bay and Delta helped, but this was limited to destinations near the water. Stage lines seemed to offer hope, but poor or non-existent roads promised to make any solution difficult.

The first attempt to address this problem came in the fall of 1849, when John Whistman established the first public transportation in California. He set out to provide regular stage service between San Francisco and San Jose, then the state capital, sixty miles to the south. Whistman, who did not even have a respectable stagecoach, relied at first on a rather dilapidated French omnibus, pulled by broken down mules and mustangs. With this equipment, Whistman established service between the two communities. At the end of the run, the animals were simply turned loose to graze.

The nine-hour ride, over a dusty trail in a jostling wagon, hardly luxurious, stopped altogether with the advent of winter rains. Unfortunately for Whistman, the winter of 1849-50 was one of the wettest on record. The ground became so soft that “wheels soon sank to the hubs.” Whistman was forced to change his route to make Alviso, only eight miles from San Jose, his northernmost stop. From there lucky passengers could theoretically make steamboat connections for San Francisco and other Bay ports.(2)

One hapless traveler from San Jose to San Francisco in December 1849 reported that he and other unfortunates boarded the stage for Alviso at 4 a.m. Because of fog, a tired team, and a “driver half blind,” they got lost, went in circles, and after an hour had gone only one mile. Finally, at 7:30 a.m., they reached Alviso (three and one-half hours to travel eight miles). They then waited another hour and a half for other stages to arrive. Finally the steamer Sacramento left around 9 a.m. and reached San Francisco at 4 p.m.(3)

Undaunted by these problems, however, Whistman re-established his entire route the next spring. The fare for the journey was thirty-two dollars or two ounces of gold, an enormous amount by today’s standards (over $600). The coach trip from San Francisco to San Jose cost about as much and took longer than a trip by airplane today from San Francisco to New York!(4)

Despite the cost, the demand was there. The business was so profitable that Whistman soon had competition. A new firm, Ackley and Maurison, which advertised “the best stages and horses the country can produce,” soon forced Whistman to sell out to yet another firm, run by Warren F. Hall and Jared B. Crandall. Hall and Crandall had both the expertise (they had previously operated a stage line in Mexico) and the capital to run a well equipped operation.(5)

With Whistman out of the picture, the competition between the two new lines was fierce. Each firm tried to increase business by shortening the length of the trip. Governor Peter H. Burnett later recalled a chilling ride in a Hall and Crandall stage, shortly after California was admitted to the Union. “After passing over the old sandy road to the Mission,” Burnett related, “there was some of the most rapid driving that I ever witnessed.” They were racing against the rival line, and the Governor reported that “people flocked to the road to see what caused our fast driving and loud shouting.” Hall and Crandall won that race, but only by a “few moments.”(6)

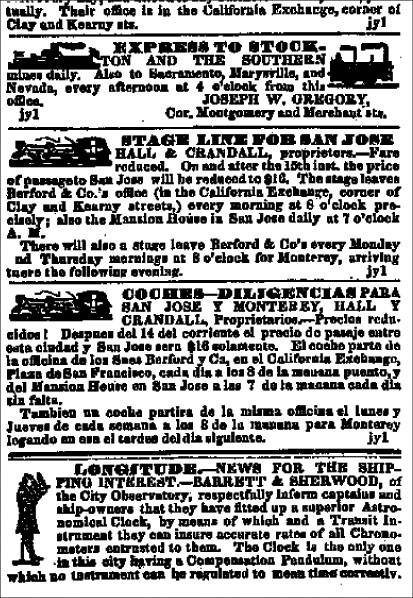

By the following year, Hall and Crandall clearly had the edge over their competition. Their business was greatly enhanced in 1851, when they received the contract to carry the U.S. mail between San Francisco and San Jose three times a week. By that summer, with their $6,000 a year mail contract, Hall and Crandall reduced the fare to sixteen dollars each way, and advertised daily service in each direction. One stage left from the corner of Clay and Kearney streets each morning at 8 a.m.; another left San Jose’s Mansion House at 7 a.m.(7) Interestingly, they advertised in both English and Spanish, relatively unusual for the time.

Hall and Crandall soon extended their line from San Jose to Monterey. These stages left at 8 a.m. Mondays and Thursdays, arriving at Monterey “the following evening.” Building on John Whistman’s venture, Hall and Crandall deserve credit for establishing the first really successful stage line in California.(8)

In addition to Whistman’s line, 1849 saw a second stage line established near Sacramento. James Birch, also with dilapidated equipment, began passenger service from Sacramento to Mormon Island on the American River. The fare for this trip was also thirty-two dollars.(9) Within two years, there were many other lines from San Francisco to Stockton, Sacramento, Marysville, and the “Southern Mines.”

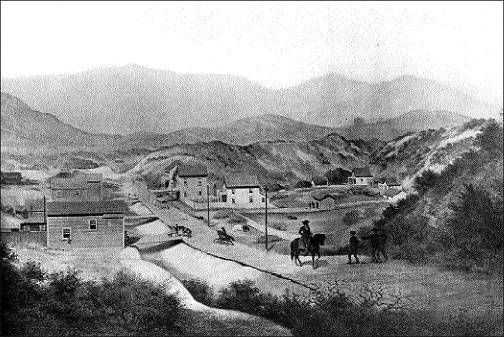

San Jose, which was the capital of California in 1849-50, was the destination of the first inter-city transportation company in California — the stagecoach from San Francisco.

Photo: California Historical Society

These stage lines helped people travel to the gold fields and from one city to another, but they did nothing to improve transportation within San Francisco. Governor Burnett’s comment regarding “the old sandy road to the Mission” only hints at the difficulties of getting around in the city.

The same winter rains that plagued Whistman also made San Francisco streets virtually impassible. Brush from nearby hills thrown into the worst spots provided little help. Almost daily, horses needed to be pulled from the mud; in one case two horses on Montgomery Street were abandoned to die when it proved impossible to pull them out.(10)

One recent arrival, writing to his family back home, reported that

…something that no doubt looks very like a street on a map…was not recognizable in its natural form, although they call it “Broadway.” It proved so to us for some got across and some got half way across and some tried to get across. But they all succeeded in getting stuck. Stuck fast in the mud, blacked boots, best pantaloons and all. “Oh, help me out!” cried one. “I can’t get out myself!” says the other. “Oh dear,” says a third, “I’ve lost my boot.” Shocking! What shall we do?” say we all. “Go on board again and wait for daylight.” And all coming to the conclusion that we never found such heavy mud anywhere at home, concluded that it must be caused by the gold in it....(11)

With the coming of spring, city officials worked to improve street conditions in the downtown area, though lack of funding hindered the attempt. They considered a proposal by Colonel Charles L. Wilson to use his own funds to build a wooden plank road out to the Mission if he were given the right to collect tolls for ten years. After that period the road would revert to the city. The Mission and the surrounding area was then considered a resort area “outside” the city. Getting there over the existing sandy and windy road, with a huge marshy bog between what is now Seventh and Eighth streets, made the trip difficult and expensive. It cost between fifteen and twenty dollars just to move a load of hay from the Mission to the city.(12)

Completed in 1851, Colonel Wilson’s wooden plank road from San Francisco to the then-distant Mission Dolores was an early attempt to connect the burgeoning city with outlying settlements.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Wilson’s scheme seemed reasonable, though it did have opposition. Finally, in November, 1850, the Board of Aldermen granted an eight-year franchise (reduced from the originally proposed ten) to Wilson’s Mission Dolores Plank Road Company for the construction of a toll road on Mission Street. The three and a half mile road from Portsmouth Plaza, down Kearny Street to Mission Street, and then out to Mission Dolores, opened in 1851.(13)

Consisting of heavy planks wide enough for teams of horses to pass one another, the road cost $150,000, nearly $70,000 per mile. Tolls ranged from twenty-five cents for a single horse and rider to one dollar for a four-horse team. So popular was the new road that Wilson and his company saw returns of up to ten per cent per month on the investment. The success of the road also increased property values and developments around the Mission.(14)

The tollhouse was on the west side of Third Street at Stevenson. “In those days,” recalled one resident twenty years later, “when you had turned the corner of Third Street to Mission Street, going west, you were pretty well out of town.” At Sixth Street, there was a bridge over the marsh (built with considerable difficulty), and on the right side was the entrance to Yerba Buena Cemetery.(15) This first plank road proved so successful that the city gave the same company a contract for a similar road on Folsom Street the following year and two additional contracts in 1853.(16)

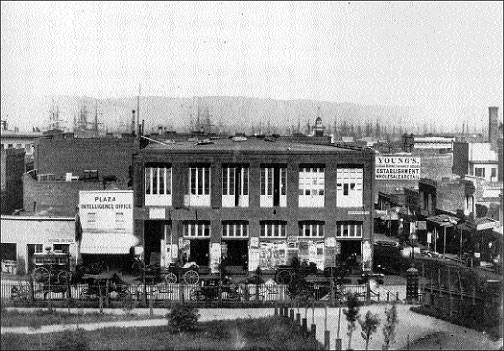

This photo of Portsmouth Plaza, taken in the mid-1850s, shows the plaza at the corner of Clay and Kearny streets. This was San Francisco’s early transportation hub. It was from here that the first omnibus line, which went out the plank road along Mission Street to Mission Dolores, set out. And it was from this corner that the stagecoach to San Jose departed.

Photo: George Robinson Fradon

In 1852, true urban public transportation arrived in the form of an omnibus line from the Post Office at Kearny and Clay to the Mission. Known as the “Yellow Line,” the omnibus was a large stagecoach, drawn by two to four horses. It accommodated up to eighteen passengers, including those who sat on top. At first, the fare for these regularly scheduled runs was fifty cents on weekdays and one dollar on Sundays, though the competition of additional lines soon reduced the fares on all lines to ten cents.

The drivers’ wages of $2.50 for a twelve-hour shift give some indication of just how expensive transportation was.(17) These drivers would need to work for nearly two weeks to afford a trip to San Jose on John Whistman’s stage coach. They would have needed to work for several hours just to ride on their own omnibus if they had a Sunday off.

Though it would many years before San Francisco and the Bay Area had adequate streets and public transportation, the early pioneers such as Whistman, Hall and Crandall, and George Wilson provided a base upon which subsequent transportation facilities could be built. These men showed that there were often better ways to profit from California gold than wallowing in icy Sierra rivers and streams.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robert F. Oaks is a fifth generation Californian, born in Escondido. He did his undergraduate work at Stanford University and received his doctorate from the University of Southern California. He taught for several years before falling victim to the Ph.D. glut, necessitating a career change into the corporate world. He is now retired, lives in San Francisco, and devotes most of his time once again to historical research and writing. His article, “Ice in San Francisco,” appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of The Argonaut.

Notes

1. Philip J. Ethington, The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850-1890 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. 2.

2. Oscar Osburn Winther, Express and Stagecoach Days in California From the Gold Rush to the Civil War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1936), pp. 81-2.

3. Frederick J. Teggart, ed., Around the Horn to the Sandwich Islands and California 1845-1850, Being a Personal Record Kept by Chester S. Lyman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1924), p. 304.

4. See J.S. Holliday, Rush for Riches: Gold Fever and the Making of California (Berkeley: University of California Press,1999), p. 346.

5. Winther, p. 82.

6. Winther, p. 83.

7. Daily Alta California, July 1, 1851.

8. Charles F. Outland, Stagecoaching on El Camino Real, Los Angeles to San Francisco 1861-1901 (Glendale, California: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1973), pp. 8-9; Daily Alta California, July 1, 1851.

9. Winther, p. 85; Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of California (San Francisco: The History Company, 1890), VII, 151n.

10. Theodore H. Hittell, History of California (San Francisco: N.J. Stone & Co., 1897), III, pp. 338-39.

11. William Smith Jewett, Letter to his family, Dec. 23, 1849 in William Benemann, ed., A Year of Mud and Gold: San Francisco in Letters and Diaries, 1849-1850 (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

12. Hittell, pp. 340-41.

13. “History of Public Transit in San Francisco 1850-1948” (San Francisco: The Transportation Technical Committee of the Departments of Public Utilities, Police and City Planning, June 1948), p. 1. Roger W. Lotchin, San Francisco 1846-1856 From Hamlet to City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), p. 169; Frank Soule, John H. Gihon & James Nisbet, The Annals of San Francisco, 1st paperback edition of the work originally published in 1855 (Berkeley: Berkeley Hills Books, 1999), pp. 296-99.

14. Hittell, p.342; Soule et al., p. 298.

15. T.A. Barry and B.A. Patten, Men and Memories of San Francisco in the “Spring of ’50.” (San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Co., 1873), pp. 108-10; Hittell, pp. 341-42.

16. Lotchin, p. 169.

17. “History of Public Transit in San Francisco 1850-1948”, p. 2.