The Hetch Hetchy Story, Part II: PG&E and the Raker Act

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

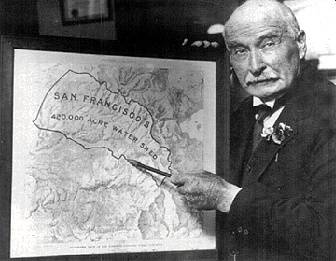

M.M. O'Shaughnessy, SF's chief engineer, points to the Hetch Hetchy watershed. He oversaw a 21-year construction process bringing water (but not power) to San Francisco.

Photo: San Francisco Public Utilities Commission

Mayor James Phelan

President Woodrow Wilson signed the Raker Act on December 19, 1913. Section 6 of the Raker Act forbade the sale of electrical power generated from Hetch Hetchy "to any corporation or individual, except a municipality or a municipal water district or irrigation district..." such as a private utility. This section had been inserted to gain the support of utilitarian conservationists like Nebraska's Senator Norris, who did not want PG&E to monopolize water and power development in the Hetch Hetchy Valley. 1

By the early 1920s, a hydroelectric powerhouse was built and enough copper wire was purchased to stretch from the Sierras to San Francisco. In 1925, it was abruptly announced that San Francisco had run out of money and could not complete the power lines into the city. The city's line ended a few hundred yards from PG&E's Newark substation on the eastern side of the south bay, conveniently close to PG&E's just-completed high-voltage delivery cable from Newark to SF. PG&E had already been purchasing Hetch Hetchy power from the city, ostensibly as a temporary arrangement pending the completion of San Francisco's own power system. A National Park Service investigation determined that the sale of power was illegal under the Raker Act, but the Interior Department refused to take action on the grounds that it was only a temporary arrangement.

In late October 1934, the system finally brought water into the city, but its power transmission lines never reached beyond PG&E's Newark substation. PG&E accepted the Hetch Hetchy power and delivered an equal amount of power into the city on its own distribution system, under a contract concluded in 1925. This arrangement was in direct violation of Section 6 of the Raker Act. Yet SF voters rejected eight bond issues between 1927 and 1941 which would have built a municipally-owned power system and obeyed the law.

The 1927 vote, after little campaigning or support from Mayor "Sunny Jim" Rolph or the supervisors, was 52,215 in favor, 50,727 against, not the 2/3 majority required for general-obligation bonds. PG&E is said to have spent over $200,000 to defeat these bond issues, including the unprecedented sum of $21,153.71 to defeat the 1930 3-year plan worked out between Mayor Angelo Rossi and the Interior Department to municipalize San Francisco power. Invariably the local media took the PG&E line that municipalizing power would amount to an unfair, forced tax on the citizens of San Francisco and that a city-run utility would lead to disaster and higher prices. All evidence by independent analysts indicate the opposite, that municipally-owned utilities generate enormous cash surpluses and provide good service.

Also in 1934, the New Deal Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes filed suit to compel SF to obey the Raker Act. The City argued that PG&E was its "agent" and it was not selling power to PG&E, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Ickes' suit in April 1940, by a 8-1 vote. Justice Hugo Black, writing for the majority, categorically rejected San Francisco arguments in favor of power sales to PG&E:

"Congress clearly intended to require - as a condition of its [land] grant - sale and distribution of Hetch Hetchy power exclusively by San Francisco and municipal agencies directly to consumers in the belief that consumers would thus be afforded power at cheap rates in competition with private power companies, particularly Pacific Gas & Electric."

San Francisco proposed a bond issue to acquire PG&E's facilities, but once again the voters turned it down. Just a few weeks before the November 1941 bond election, PG&E announced sweeping reductions in local electricity rates. The Chronicle carried the story on the front page and the bond act went down to defeat. Interior Secretary Ickes informed Mayor Rossi that he had no choice and began moving to revoke San Francisco's Raker Act grant and take over the Hetch Hetchy Dam, but a month later Pearl Harbor changed everything.

Near the end of WWII, SF stopped supplying Hetch Hetchy power to a war-time aluminum plant and a federal court gave the city six months to comply with the Raker Act. By July 1945 a strange compromise had been achieved, in which SF contracted with PG&E to sell Hetch Hetchy energy to the Modesto and Turlock irrigation districts and also took two industrial customers from PG&E. When Ickes allowed a temporary authorization for this deal, the illegal arrangement whereby San Francisco had been allowing the privately owned Pacific Gas & Electric Company (the U.S.'s largest utility, headquartered in, where else, San Francisco!) to sell electricity and gas to San Francisco residents at prices up to four times what it might be if it were publicly owned and distributed, was given a de facto endorsement by the Federal Government, in spite of the law and the U.S. Supreme Court!

By 1948, San Francisco was selling over 5 million kilowatt hours a year to PG&E. The story goes on but was soon forgotten by local citizens as the pro-PG&E newspapers completely ignored the ongoing scandal.

In 1964 a UC Berkeley biochemistry professor Joe Neilands, active in the (ultimately successful) effort to stop PG&E from building a nuclear power plant at Bodega Bay, stumbles across the Raker Act story. He writes to the Interior Department and receives bland assurances that there is nothing to be done. When he publishes his story in the San Francisco Bay Guardian in 1969, the saga re-emerges as a scandal in SF politics, but continues to be systematically ignored by the local daily press and political establishment. In 1973 the civil grand jury concludes that the city is required to operate its own public-power system, and that the city's contracts with Modesto, Turlock and PG&E are of "questionable legality." The grand jury's report is never publicized and disappears into the bureaucracy.

In 1984, then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein concludes ridiculous deals with the Modesto and Turlock irrigation districts, selling them Hetch Hetchy power through the year 2015 at close to cost. She is convinced to do this by Congressman Tony Coelho (who resigned under a cloud during the S&L crisis of the late 1980s), who has threatened to re-open the Raker Act scandal in a congressional committee, which could possibly lead to the Federal government seizing the dam and its power and revenue. Feinstein eventually concludes a deal (on extremely favorable terms for PG&E) to continue paying the private utility millions of dollars a year in "wheeling fees" to deliver power to SF residents, and wherein the utility continues to sell power to SF residents at inflated rates to provide guaranteed profits to its shareholders.

In 1988, just-elected Mayor Art Agnos is summoned to PG&E headquarters to meet with Chairman Dick Clarke and is told that PG&E controls enough votes on the Board of Supervisors to block any attempts to void the deals its has forced on the city. Agnos faces a $20 million budget deficit, but never speaks publicly about the possibility of getting that money from PG&E or public power. Instead he slashes services and the budget, leading ultimately to his ouster in the next election by his former police chief, Frank Jordan.

In 1994, as the Army's Presidio base was about to be handed over to the National Park Service, a new scandal erupted when it was revealed by the Bay Guardian that PG&E had convinced the Park Service planners (influenced by the corporate-sponsored Presidio Council) to pay PG&E up to $11 million to take over the publicly-owned, albeit run down and obsolete, electrical distribution system on the Presidio, and then run it as part of their profitable monopoly utility business.

In 1996 a liberal Board of Supervisors established a select committee on Municipal public power, which in turn commissioned a feasibility study on the costs and benefits of municipalizing PG&E. Once again, PG&E managed to control the process, ensuring that a consultancy with long ties to the utility would conduct the test. Although the Bay Guardian and supporters managed to cast a cloud over the study, the Supervisors' committee itself was eliminated by the newly-elected president of the Board of Supervisors, Barbara Kaufmann, at the beginning of 1997. Again, San Francisco's legal responsibility to sell wholesale power to its citizens was derailed by the powerful manipulations of the largest privately owned utility in the U.S.

For a look at how the other side of this public utility equation is nearly as corrupt, see "Who Pays for Public Water?"

Notes

1. For the complete, blow-by-blow timeline on one of the longest running municipal rip-offs and scandals, seek out the September 22, 1993 issue of the San Francisco Bay Guardian in which all the brazen details are laid out covering 1913-1993. And the story continues. . .