Truckaderos and the West Coast Food Network

Historical Essay

by John Curl, Part Six of an excerpt from a longer essay “Food for People, Not for Profit: The Attack on the Bay Area People’s Food System and the Minneapolis Co-op War: Crisis in the Food Revolution of the 1970s”

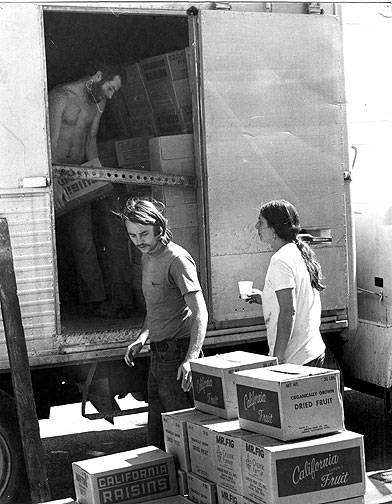

Workers at the Cooperating Warehouse loading dock, c. 1976.

The San Francisco Bay Area People’s Food System was not the only local network of food collectives and co-ops on the West Coast. Over a dozen collective warehouses serviced an extensive web of hundreds of grass roots co-op stores and food buying clubs scattered from Southern California to British Columbia. All of these had sprung up independently in the same time period. Each warehouse did some of its own local trucking, but independent trucking collectives ran most of the routes between the warehouses and the rural stores. The warehouses served as depots and exchanges for local products and loads transferred between truckers in different routes. The warehouses, and to some extent the truckers, took the leadership in raising the alternative food network to a more highly organized level.

Truckaderos, an independent trucking collective of five members and one truck, was based in the Bay Area and did much of its work for the Food System, running the routes to the south and east. Truckaderos worked only for food co-ops and collectives. North of San Francisco was the territory of other collective truckers. At that time there were at least fifteen different cooperative trucking groups in California, with different routes crisscrossing the state and beyond.(44)

Truckaderos usually arrived at the Food Factory on Monday evening between 5 p.m. and 9 p.m.. Everyone in the Food System was invited to come down to help unload or just hang around, dig the scene, and pick up information about what was happening in other West Coast co-op warehouses. Truckaderos kept up on what was happening in the West Coast food collective and co-op world.

They made two weekly runs. Their east run was to Davis, north to Yuba City, Oroville, and Paradise, then back to San Francisco. The next day Truckaderos were off to Gilroy, Los Baños, Fresno, Tulare, Bakersfield, winding up at Southern California Cooperating Community (SCCC) in Los Angeles. On alternate weeks they continued south to Solano Beach, Ocean Beach and Linda Vista, sometimes east to Indio-Coachella, then back to Los Angeles. They returned north via the same route in reverse, except sometimes they cut east to Lindsay and Fresno before heading back to San Francisco.45

In early 1974 Truckaderos founders Leon Willard and Peter Waring decided to drive north and tour the collective and cooperative warehouses between San Francisco and British Columbia, which they’d never visited. They wanted to better understand the situation and the movement, and to help improve interconnections and communications among groups. They went “from collective to collective, meeting the people involved, and gathering first-hand information, . . . consolidating this information, and making it available to the rest of the food system.”(46) They explained that before they started Truckaderos, “One of us had been a member of the Desert Collective [Coachella], doing most of their trucking, and the other of us had been with Southern California Cooperating Community (SCCC) [Los Angeles-Santa Monica] as a warehouse worker and trucker.

Our reason for leaving our respective collectives was to form a trucking collective to provide the food system with a reliable and efficient trucking service, something that did not exist at that time. It was our belief that we were not just moving food but participating in a new economic and social system as well.”(47) When they used the term food system, they were referring not just to the San Francisco Bay Area Food System, but to the regional network and beyond. They saw themselves as part of a growing community building an alternative society, “a model which demonstrates the viability of the things we believe in.”

They thought they knew what had gone wrong in the failures of two local pioneering collective distributors: Westbrae was financially successful but no longer a collective; Altdisco went bankrupt because it was too isolated from the movement. (Altdisco, closely connected with Ma Revolution, would surely have disputed that.) Truckaderos concluded that, “a collective could not survive unless its consciousness extended beyond the confines of its own structure. Westbrae [Natural Food Distributors] had come to believe that collectives could not work, and had opted for the corporate structure. They were no longer an alternative to anything except in the kind of food they carried. Alternative Distributing [Altdisco], though now defunct, always presented themselves as a collective, but did not work very collectively with other groups.”(48)

Outside of the Bay Area, the most developed region on the West Coast was said to be around Seattle. “Workers’ Brigade was generally considered the most righteous, but no one really knew for sure who or what Workers’ Brigade was, or how they related to C.C. Grains or Community Produce. Starflower was generally considered just another corporation like Westbrae, though rumor had it that they were a Feminist Collective. But no group had checked it out to see what that meant.”

In September, 1975, Free Spirit printing collective in Oakland published the result of that tour in a pamphlet entitled, Beyond Isolation: the West Coast Collective Food System As We See It. It was distributed widely among the West Coast food collectives, co-ops, and warehouses. Mostly written by Willard, the pamphlet presented a snapshot of many of the warehouses and laid out many of the controversies within the network. Truckaderos explained that from SFCW, they “learned of the worker controlled, anti- profit approach to meeting our needs. SFCW was an inspiration from the very beginning, and contributed greatly to our establishing guidelines and sticking to them.”

SAN FRANCISCO COOPERATING WAREHOUSE: SFCW is the most politically consistent warehouse we know of. They were the first example of a worker-controlled anti-profit collective we came in contact with and reflect less individualism than most other collectives. They [refuse] to sell to profit makers, and once they decide to support a group or effort, that support is considerable. SFCW is readily open to suggestions or criticism and are quick to correct errors in judgment if and when they make them. Their collective consciousness has always reached beyond their individual collective and is often visionary. Their internal structure seems at times to be overly rigid, making input from outside the SF community difficult. Many of the persons in SFCW have worked and struggled together for quite a long time, giving each a great deal of experience with collective organization, and a high concentration of political awareness. [Ed. Note: Details of other west coast food co-ops from LA to Seattle are in the original article.]

Workers at the Cooperating Warehouse loading dock, c. 1976.

Truckaderos also visited many co-op stores on their trip and found that almost all of them had “a strong prejudice against canned, non-organic, or non-food items.” Now that they had made their tour, the Truckaderos offered observations, criticism, and suggestions. “Many places we went we saw signs of the same predicament: Too much work, too few people, and inadequate equipment for the magnitude of the task we had undertaken. About the only thing we had in abundance was youth and enthusiasm.” They observed that, despite their different locations, the various warehouses had a common set of problems, while the stores had a distinctly different common set of problems. The stores were “essentially volunteer-run by non-paid workers resulting in high worker turnover, thus the constant need for training of new workers, and the resulting inefficiency. There may be some token ‘food credit’ but never enough to meet all the needs of the workers, forcing them to obtain the rest of their survival needs from outside the food system. The existing stores are too small and too few to actually supply the total needs of any communities they believe themselves to be serving.”

In contrast, most of the warehouses were run almost entirely by paid workers.

Most warehouses are organized as collectives, and those few that aren’t are rapidly moving in that direction. These warehouses, whether born out of a need by their community stores, or coming into existence on their own, carry those items stocked and sold by the coop stores. The warehouses, like the stores, are working at near capacity. [They are] too small, too inefficient, and self-limiting internally by attitudes against size, expansion, and technological aids, to adequately deal with any sharp increase in the number or size of stores. Although the collective food system has substantial economic power as a whole, the fact that each warehouse continues to buy independently, greatly reduces that collective strength, keeping most of them in precarious financial situations unnecessarily . . . .

They found among the West coast warehouses “no on-going effort to unify, though it would be in everyone’s best interest to do so. [A]lthough some collectives were, in fact, working together, it was being done mostly where it was to their economic advantage, rather than out of any sense of solidarity or mutual commitment.”

Truckaderos proposed that they try to move toward an economic merger, and were encouraged by recent exchanges between SFCW, Minneapolis People’s Warehouse, and Tucson People’s Warehouse, as indications that a higher level of collectivity among food warehouse collectives was possible. “Buying together and cooperating in food distribution. Not for profit, but to meet their own needs and the needs of the community in which they lived. It seemed like a dream come true.”

They ended their tour on an optimistic note: “The collective is the core of it all. Collectives have, over the past few years, grown stronger within, and now it is time to extend that strength, to unify and strengthen the collective network. From that, along with the ability to feed ourselves, comes the foundation upon which to build the new society. We must learn to believe in ourselves, for it is from among us, that the solutions will come.”

Collective and Co-op Farms

The cooperative/collective network did as much business as possible with the significant number of cooperative and collective farms that operated in the 1970s. Cascadian Farm, today a huge natural foods corporation quietly owned by General Mills, and a vivid example of the impact the corporate system has had on agricultural and food-related co- ops over time, began as a collective farm connected with the Seattle-area Cooperative Communities food system and did business with Seattle Workers Brigade. In a 1977 article in The Tilth Newsletter, Gene Kahn, one of the farm’s founders (and now a General Mills vice-president), wrote:

Cascadian Farm is a collective commercial farm located in the upper Skagit Valley about 50 miles east of Mount Vernon, Washington. The farm has been growing various vegetables since 1971 and began an expansion into field crops such as rye, barley, and potatoes in 1975. Our crops have been sold primarily to CC Grains and Community Produce in Seattle, and to the Fairhaven Cooperative Mill in Bellingham. The five farm members live together in various small houses on the home farm near Rockport; we are currently (1977) cultivating about 75 acres of crops on four different leased farms. It was a wonderful feeling when we arrived at CC Grains in Seattle with the first load from our first harvest. There was a feeling of unity and appreciation for the cooperative food distribution system. Historically, farmers (and particularly small farmers) have found it necessary to form cooperatives in order to survive. Such coops, which generally are established to take over processing functions and—to an extent—vertically integrate farm production, help to give small farmers a much greater chance of success. This can best be accomplished through the formation of local rural producer’s cooperatives.(54)

Many Latino farmworker groups started cooperative farms in California in this period, and the collective food distribution network was very happy to have them onboard. By one estimate, forty to fifty of these “limited resource” cooperative farms started in the early 1970s. The most successful were Cooperativa Campesina and Cooperativa Central, which both planted strawberries, typical of most of these co-ops. Campesina put in their first crop in 1971 on 80 acres of land near Watsonville; by 1976, the cooperative had 178 acres of berries and an annual gross income of over $1.4 million. Central grew its first crop in the summer of 1973 near Salinas, and by 1975 its assets had grown to over $650,000.(55)

Initially financed through cobbled-together public and private funding sources, the farmworker co-ops ranged in size from several families to seventy-three families. Almost all were organized by the parcel system, with the cooperative usually responsible for planting, irrigation, mulch, etc., and each member family responsible for maintenance and harvesting of parcels totaling 3 to 5 acres. Most cooperatives required collective marketing, and returned to each family the market price of its produce minus the co-op’s operating expenses and a contribution into a revolving fund.

Some of these “limited resource” cooperative farms were short-lived, and in 1976 only 15 remained in the state. However, organizing again took an upswing, and five years later there were at least that many in the central coast area alone, and many more statewide.

Notes

44. Turnover 10, March 1976, 35.

45. Ibid.

46. A Peoples Cooperating Communities Trucking Collective, Beyond Isolation: The West Coast Collective Food System As We See It, (Oakland: Free Spirit, 1975), 4.

47. Ibid., 2.

48. Ibid., 3.

49. Ibid., 5-8.

50. Peg Pearson and Jake Baker, “Seattle Workers’ Brigade: History of a Collective,” in Workplace Democracy and Social Change, eds. Frank Lindenfels and Joyce Rothschild-Whitt (Boston: Porter Sargeant Publishers, 1982).

51. Gwen, “C. C. Grains: Sharing the Changes,” Out and About, April 1978, 12. Quoted in Gary Atkins, Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 140.

52. Beyond Isolation, 8.

53. About Us, “TCW Food Coop.”

54. Gene Kahn, “Building the Granary at Big Lake,” The Tilth Newsletter (Summer, 1977).

55. Miriam J. Wells, “Political Mediation and Agricultural Cooperation: Strawberry Farms in California,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 30, no. 2 (January 1982): 413-432.